The journalist behind USA Today’s recent investigation explains why other reporters should dig deeper into school-based equity efforts that may not help kids — and offers to share her research.

By Katherine Reynolds Lewis

Despite billions of dollars that schools and districts in the U.S. spend on equity plans and equity-oriented professional development annually, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx students continue to achieve at lower levels than their white and Asian American classmates.

Black high school seniors not only perform worse on average than their white peers in reading, but their scores are lower than those of white 8th graders, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

However, media coverage on efforts to improve these dismal outcomes has focused mostly on racial justice curricula for students rather than interventions aimed at changing teachers’ hearts, minds, and practices.

That’s why I spent three years researching what the biggest districts in the nation were doing to improve outcomes for BIPOC students, resulting in a recent pair of USA Today stories As US schools become more diverse, patchwork equity efforts fall short (including a sidebar about the organizations that dominate school DEI training).

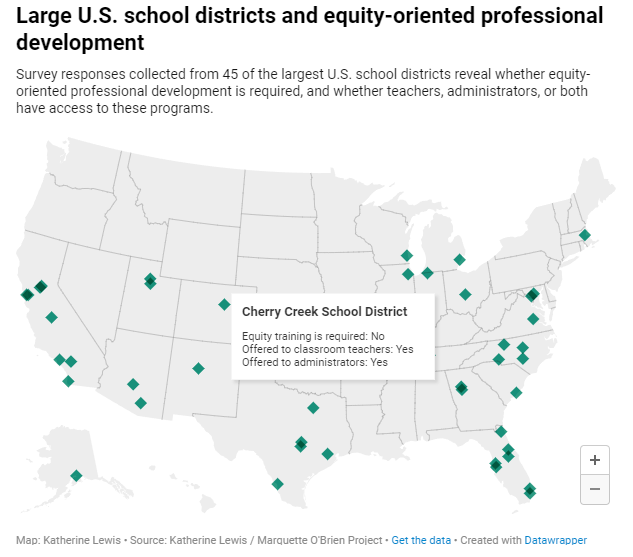

Above: District-level information about professional development programs from the USA Today investigation. Click to see the full visualization or contact the author about further collaboration.

What I found isn’t pretty. Schools spend almost $20 billion on training for teachers nationally, much of it aimed at achieving equity. But none of 45 large U.S. school districts who responded to my inquiries measure program impact with an evidence-based metric developed from research on what works.

However, my reporting only scratches the surface of the questions taxpayers and families deserve to know about how teachers are being supported to deliver an equitable education across racial lines. There are so many things that local education reporters could do to build on these findings and conduct original reporting, including Freedom of Information Act requests and in-person observation.

With the majority of teachers being white women and most U.S. students being children of color, the racial disparities in achievement and opportunity won’t disappear without systematic change, rigorous evaluation, and long-term commitment to equity.

Media coverage on efforts to improve these dismal outcomes has focused mostly on racial justice curricula for students.

When my reporting team — myself and two then-Marquette students — began our research, we wanted to understand where equity-oriented teacher training lives in school districts and how to get answers from reluctant or uncooperative districts.

Given how fragmented and locally governed public education is, we weren’t surprised to discover very different answers coast to coast. Districts might have a chief academic officer or director of professional learning who oversees all PD. Some districts have an equity office that promulgates equity-oriented training. And, of course, individual principals and cluster leaders provide additional support, as do counselors, curriculum specialists, and equity leads (which some districts have) within individual school buildings.

Most school districts set aside only a handful of professional development days for all training, so much of the learning is happening informally or within schools. And we know that professional learning can include anything from a teacher returning from a conference and presenting a rough summary of what she learned to a full-blown polished presentation and set of exercises from consultants who train teachers every day across the country. This complexity and level of detail made it hard to draw sweeping conclusions on a national level, but local journalists will be able to convey the specifics of what’s happening in their districts.

Much of the research finds that the majority of teachers are unprepared to work in diverse settings and that slipshod professional learning can actually do more harm than good. For example, bias training runs the risk of reinforcing stereotypes or making participants more resistant to change.

The majority of teachers are unprepared to work in diverse settings… slipshod professional learning can actually do more harm than good.

Some districts, such as Milwaukee, make a baseline equity professional development course mandatory for all teachers and plan to build on it every year.

Others told me that mandatory training provokes resistance, and instead they take a voluntary approach with more focus on principals and equity champions to spread best practices through persuasion, not compulsion.

Erin Hanson, assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction in Sacramento, was particularly frank on the challenge of addressing bias and achieving equity:

“You can’t just do a training on compassionate dialogue and expect that everyone is suddenly going to be capable of having compassionate dialogue; you can’t just do a training on implicit bias and think that now everybody’s going to always stop and pause and understand their own biases,” Hanson said.

“We can get all the funding, but then we have to be able teach our adults to change their mindsets about our role as educators.”

If you’re in luck, your district responded to my query and some of their key experiences are related in my piece or data set. (The map shows which districts responded.) I am open to collaborating with journalists who want to pursue similar reporting in their coverage areas; if a school district near you is one of our respondents and you’d like to learn more, contact me at Katherine@KatherineRLewis.com.

The Civil Rights Data Collection is a good starting point for assessing a district, although data are always a few years old.

When approaching school districts to learn more about how they measure the effectiveness of their equity training, here are some questions to ask:

- How do you support teachers and school leaders in understanding the policies and practices that may disproportionately impact students of color and those with disabilities? How many days are devoted to such development, and is it mandatory or optional? Do you talk about race explicitly?

- Who provides equity-oriented teacher training in your district or school? Do you use an outside vendor and if so, how do you ensure that the learning continues after the training ends? Who are the district-employed individuals responsible for outcomes?

- How much money do you spend? Which budget does it come from?

- In what ways do you measure the impact of professional development?

In situations where the district isn’t cooperative, a local journalist could file Freedom of Information Act requests to compel uncooperative districts to share how they’re spending taxpayer money on teacher training. They could also FOIA the names of vendors who provide equity-oriented training. These strategies would work well for local journalists who are hoping to report in this area.

For national experts, you might try some of the people whom I relied on for my work: Rita Kohli at the University of California Riverside; Andrew Matschiner, a visiting assistant professor at Miami University in Ohio; Hillary Parkhouse, an associate professor at Virginia Commonwealth University; and Daren Graves at Simmons University.

My team relied on research showing that the effectiveness of professional development depends on:

- The relationship of the presenter or facilitator to the audience,

- Whether the learning takes place in context and feels relevant to the audience’s work, existing knowledge, and daily challenges or student population,

- Whether there’s an opportunity for reflection, practice, and interactivity in the training, and

- Whether participants can immediately implement takeaways and continue their learning by incorporating feedback and real-world experience supported by a coach, professional learning community, or other method.

I am open to collaborating with journalists who want to pursue similar reporting in their coverage areas.

For this yearslong project, I interviewed hundreds of teachers, scientists, students, and racial equity trainers. Funded first by a Knight Science Journalism fellowship at MIT and then an O’Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University, I read hundreds of research studies on how bias forms, evidence of racial and gender discrimination, and attempts to change disparities across fields.

My O’Brien team reached out to the 100 largest school districts, and we heard back from 45 of them, giving us an exclusive data set on the state of equity-oriented professional learning. The three of us spent a combined 24 days of in-person reporting across the U.S., culminating in our USA Today story that several Gannett papers have also published. I personally spent 750 hours starting in August 2021 and culminating more than a year after my fellowship ended.

While districts couldn’t draw a direct line from a particular intervention to the impact on the organization or student, most of them are collecting information in several categories. That can inform their decision making about what professional learning should continue or stop doing.

I began this project fascinated that districts spend billions of taxpayer dollars on diversity, equity, and inclusion professional development with very little transparency or public insight into the impact of that training. That doesn’t serve students or educators.

It is too easy for district leaders to throw money at the problem of inequity and then blame the teachers for not changing. Districts must also do better in recruiting teachers of color, creating school cultures that retain those educators, helping school leaders understand their own biases, identifying and changing discriminatory practices and policies, incorporating trauma-informed instruction and discipline practices, and drawing on the assets of their families and communities.

Katherine Reynolds Lewis is an award-winning science journalist, author and speaker based in the Washington D.C. She is a 2021-22 O’Brien Public Service Journalism fellow and 2020-21 MIT Knight Science Journalism fellow, reporting on the science of racial bias in pK-12 education. You can follow her at @KatherineLewis and read more about her work here.

Previously from The Grade

Concerned about school inequality? Write more about local control (Morgan Polikoff)

How do we get Black kids’ literacy to matter? Have more journalists cover it. (Colette Coleman)

Covering gifted education through an equity lens (Holly Korbey)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

The Grade

Launched in 2015, The Grade is a journalist-run effort to encourage high-quality coverage of K-12 education issues.