To understand education inequality, researcher and author Morgan Polikoff calls for more education journalists to examine local control’s effects on curriculum quality and other aspects of students’ educational experiences.

By Morgan Polikoff

In education in 2021, it’s All. Equity. All. The. Time.

Equity is a focus of state and federal reforms, like the large federal spending boosts under the American Rescue Plan. And equity is a driver of highly prominent curriculum reforms, like the attempt to correct the historical record through the New York Times’ 1619 Project.

Liberals and progressives like myself love to talk about and work on educational equity, designing policies and measuring the impact of our efforts by their effects on long-standing opportunity gaps.

We liberals also like big government, and we think (rightfully) that only the higher levels of government can really bring about equity through policy. For instance, local control of school funding is what brought about funding inequities that widened opportunity gaps — state and federal efforts have been necessary to right these wrongs and to get to more equal (let alone equitable) funding systems.

But while the example of school funding is paradigmatic for showing how local control leads to school inequality, this is far from the only policy area that merits attention for the pernicious role of local control in undermining educational equity.

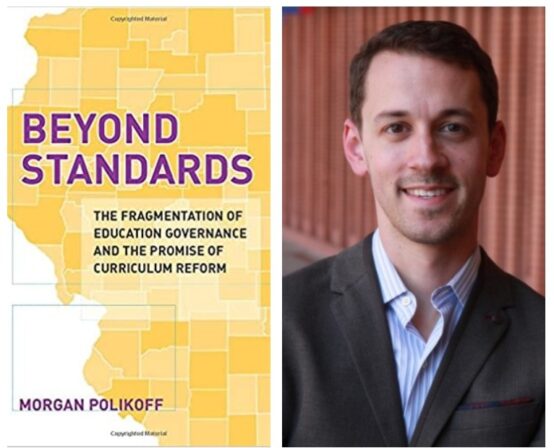

As I talk about in the final chapter of my new book, Beyond Standards, we liberals and the journalists who write about schools too rarely grapple with the many other ways that local control directly causes the very inequalities we say we want to solve.

To learn more about how the media covers education, follow The Grade on Twitter and Facebook.

As I talk about in the final chapter of my new book, Beyond Standards, we liberals and the journalists who write about schools too rarely grapple with the many other ways that local control directly causes the very inequalities we say we want to solve.

There are so many examples of local control-fueled inequality that need more attention from journalists:

One obvious example where local control plays a negative role is school district boundaries (and even local attendance zones within districts). Since the Supreme Court made district boundaries impermeable to desegregation efforts, hundreds of mostly white districts seceded from more diverse districts, widening inequities right in front of our eyes. The organization EdBuild documented the profound effect of school district boundaries on inequality, and anyone who has bought a house in an urban area can attest to the powerful role of local school catchment areas in driving up house prices and causing stratification.

Schooling during COVID offers another example of when local control has hindered as much as it has helped. States have mostly left local actors flailing in the winds and have rarely offered the kind of strong, specific support districts needed throughout the year-plus turmoil. This burdened local educators with tasks they were never trained for, widening long-standing inequalities by race and income and resulting in low-income students and students of color being locked out of in-person learning at wildly disproportionate rates. Some evidence suggests these disparate experiences contributed to the school hesitancy gaps that we are now seeing across racial/ethnic groups and that will not simply go away at the start of the next school year.

For more on local control’s impact on school safety decisions, see this recent Washington Post op-ed: Leaving it to school boards to vote on mask rules is asking for trouble.

There are so many examples of local control-fueled inequality that need more attention from journalists.

Another example — and the main focus of my book — is local control’s effect on curriculum materials, and the ways that decentralization contribute to poor quality curriculum and widely varying educational opportunities.

Routinely, states leave our 13,000 districts out to sea when it comes to identifying, adopting, and implementing core curriculum materials. While some states put out advisory lists of materials for districts to consider, most districts still feel the need to evaluate multiple available materials using duplicative and onerous processes. This burdens local educational leaders with work that could have been better done by experts at the state level, requiring them to go about the complicated task of choosing and supporting materials. Furthermore, what curriculum policies there are at the state level are often only in a few subjects and grades (always math and English, sometimes science or social studies).

This decentralization filters even further down to local schools and even classrooms. In a recent study I codirected, we found that almost two-thirds of the English language arts teachers we surveyed across three states did not have access to standards-aligned core materials. Interestingly, we found there was greater access to aligned core materials in schools with more low-income students of color, perhaps because these schools are often in districts that are more tightly controlled.

Worse, many teachers are given no core materials at all and instead must source curriculum of totally unknown content or quality from Pinterest or Google. These materials are often rated poorly by experts and are insufficiently challenging to students, but there is close to no supervision of teachers’ curriculum supplementation in our highly decentralized systems. Only a few districts carefully structure teacher supplementation efforts in ways that support, rather than undermine, the core curriculum.

Sign up here for our free newsletter featuring the week’s best education news & newsroom comings and goings.

Another example — and the main focus of my book — is local control’s effect on curriculum materials, and the ways that decentralization contribute to poor quality curriculum and widely varying educational opportunities.

Of course, I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that it is also all too possible for state involvement in curriculum to be its own form of disaster. We are seeing this happen in front of our eyes, as state departments of education in conservative states seek to root out critical race theory (CRT) and its codewords (e.g., social-emotional learning apparently) in curriculum materials.

Indeed, local control serves some important purposes. For instance, parents are pretty happy with how their local school districts handled the pandemic. And recent state-level insanity about critical race theory may be more damaging than letting individual districts make the CRT curriculum decisions they think are best for their own children.

But there is insufficient attention paid to the downsides of local control, and these are more and more apparent by the day in the post-COVID world.

There is insufficient attention paid to the downsides of local control, and these are more and more apparent by the day in the post-COVID world.

We need careful investigations of the quality of the materials that are being used in school and districts. Are they factually accurate? Are they aligned with the science of learning? Do they include diverse authors and topics? Are they organized and easily used? (While there are experts and organizations that can help you evaluate the materials your district is using, there is no national organization like EdReports to evaluate supplemental materials that teachers choose and use on a daily basis.)

But that’s not all. We also need to hear more from reporters about the quality of online learning options being provided by thousands of individual districts, and we need to interrogate why these options aren’t being provided more centrally (again, in ways that reduce burden on local actors and almost certainly increase overall quality).

We need to hear more about curriculum materials that are actually being used in local districts, schools, and classrooms, and we need to probe the ways that decentralized decision-making often results in the kinds of profoundly offensive or downright racist materials that make the rounds on social media every few months. While these individual stories are often in the news, it is rare that the stories address the structural issues that gave rise to the individual offensive lesson.

And we need to hear about local school boards, their representation of the constituencies they are supposed to be serving, and how their decisions do and do not reflect the needs and desires of the children they serve.

There are examples of this kind of important investigative reporting, such as this data-driven analysis from Vox, this discussion of school board diversity from Education Week, and this recent discussion of social studies curriculum issues from Hechinger Report.

More than individual stories about all of the above, we need serious investigations of the strengths and weaknesses of local control structures, especially in the most decentralized states (which often happen to be highly populous and quite blue).

As states plot a course forward post-pandemic and with an increasing focus on educational equity, there may be a window for them to reconsider some of these decentralized structures that burden educators and cause our most underserved children and families to be even more left behind.

Related commentary from The Grade:

How do we get Black kids’ literacy to matter? Have more journalists cover it.

Covering the debate on teaching race in schools

The media blind spot hiding a big problem in American classrooms

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Morgan Polikoff

MORGAN POLIKOFF is an associate professor of education at the Rossier School of Education of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.