Black children are overidentified for behavior issues at schools and underidentified for mental health concerns.

On April 8, 2014, Karyn Washington, creator of the For Brown Girls web site, committed suicide. Just 22 years old, Washington reportedly had dealt with depression and mental illness for much of her life and had created For Brown Girls to promote self-love for black girls who struggle to embrace their dark features.

What access to mental health services did Washington have as a student? What cultural considerations would mental health professionals in school settings have given to her and other black girls who contend with the same self-esteem and body image issues that all girls confront as well as the racialized and culture-specific issues related to skin color, hair, and white standards of beauty?

Now think of the archetype of the black male student who is labeled emotionally/behaviorally disturbed because he is perceived to be impulsive, aggressive because he acts out and gets in fights, and exhibiting learning difficulties because he performs below grade level. According to the U.S. Department of Education, black children are almost three times more likely than white children to be labeled as having a mental disorder and almost twice as likely to be labeled as having an emotional/behavioral disorder (Losen & Orfield, 2002).

Are black boys really disproportionately emotionally and behaviorally disturbed compared to other students? Or are they reacting to the biases and the cultural incompetence of teachers and mental health professionals who often harbor negative stereotypes about them?

Now consider the highly publicized incidences of violence against black teenagers. Fifteen-year-old Hadiya Pendleton was shot and killed on Chicago’s South Side, one week after performing with her high school band at President Obama’s 2013 inauguration. Unarmed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was killed in Sanford, Fla., by volunteer security guard George Zimmerman, who perceived him to be a threat. In Ferguson, Mo., a white police officer killed unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown in broad daylight.

The psychological effects of violence are long-lasting. Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder are undoubtedly high among black youth who are frequently exposed to random and senseless acts of violence, either by other black youth or by police. How prepared are school mental health professionals to deal with the psychological and emotional aftermath of black students struggling with the seemingly low value placed on black life?

These are examples of mental health challenges that we believe uniquely affect black students. However, far too little attention and research has examined the specific mental health needs of black students. And urban areas offer less mental health care to African-American and Latino students than their white peers (Howell & McFeeters, 2008).

According to the Children’s Defense Fund, black and other racial/ethnic minority children have many unmet mental health needs (Children’s Defense Fund, 2010). Complicating matters is the interaction of low socioeconomic status with mental health functioning. Because a disproportionate number of black and racial/ethnic minority children are from low-income families, their mental health needs can be overlooked or misinterpreted as other problems.

Socioeconomic status and race

A critical component in understanding mental health issues in black communities is recognizing the connection between mental health and socioeconomic status. Individuals living in poverty are more likely to experience psychological distress because of insufficient familial, social, and psychological resources (Wickrama & Vazsonyi, 2011). According to the 2011 American Community Survey (U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.), 39% of children younger than 18 living in poverty are black. Thus, about 4.3 million black youth are confronted with race and poverty-related stressors.

Individuals living in poverty are more likely to experience psychological distress because of insufficient familial, social, and psychological resources, and 39% of children younger than 18 living in poverty are black.

Experiences common to low-SES populations include single-parent households, overcrowded homes, multigenerational experiences of financial stress, exposure to neighborhood violence, and substance abuse. All of these bring their own share of challenges and can be overwhelming to cope with for low-income black adolescents already dealing with common development stressors related to puberty, peer-related stress, academic motivation, and identity formation. The interaction of race, low socioeconomic status, and culture interact in ways that make the detection of mental health issues among black students more challenging.

Racial disparities

Exploring how teachers perceive and respond to black students’ behavior affects mental health outcomes. Educators are gatekeepers for the interventions students can receive when problems are identified. If educators fail to critically interrogate their responses to diverse students, they risk criminalizing what are essentially symptoms of psychological distress. Furthermore, the pervasive negative stereotyping of blacks can bias teachers toward addressing externalizing symptoms (e.g., delinquent and aggressive behavior) rather than being sensitive to their underlying internalizing causes (e.g., depression and anxiety). This limited focus on underlying mental health concerns can, in turn, lead to punitive responses from educators.

For more than three decades, black students have been disproportionately affected by exclusionary discipline practices, such as special education placements, suspensions, alternative learning center placement, and expulsions. These practices are often based on interpreting culture and behavior within a universal perspective rather than seeking to understand culture and behavior within a black context.

Black children who are sanctioned at school are less likely to have their misbehavior attributed to internal sources, such as depression or anxiety.

Exclusionary discipline practices start early. For example, black preschoolers are three to five times more likely to be expelled from school than their Asian-American, Latino, and white peers. Nationally, black males are 2.9 times more likely to be identified as mentally challenged as their white peers (Moore, Henfield, & Owens, 2008). More disturbing, one study found that black students were more harshly penalized than their white peers for similar behavioral infractions (Skiba, Michael, Nardo, & Peterson, 2002). This study also found that black students were disproportionately sanctioned for more subjective forms of misbehavior, such as “disrespect, excessive noise, threat, and loitering” (p. 332). These findings suggest that teachers’ perceptions and their subsequent reactions to students’ misdeeds may be moderated by students’ race. These differential actions contribute directly to the school-to-prison pipeline for black youth (Alexander, 2010) and ultimately negatively affects their mental health.

Often, black children who are sanctioned at school are less likely to have their misbehavior attributed to internal sources, such as depression or anxiety. Identifying potential psychological causes not only would reduce the criminalization of behavior that is better explained by underlying mental health concerns but also would encourage educators to use different interventions. There is evidence that when black students present with the same internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety) as white students, they are viewed more extremely. A recent study that compared depression-related symptoms for black and white adolescents found no differences in symptom severity when adolescents rated themselves (Stein et al., 2010). However, when rated by nonblack observers (one Latina and one white), black youth were rated as demonstrating more severe symptoms when compared to white youth. Different perceptions of the same behavior can lead to racial disparities in exclusionary discipline. Misbehaving white students may be labeled as having “made a mistake and got caught,” whereas black students may be classified as “oppositional and noncompliant.” These different explanations inevitably lead to disparate responses from teachers. The recommendation for a white student likely would incorporate mental health counseling, while a black student would more than likely be subject to exclusionary discipline. Therefore, teachers should work to understand what underlies the student’s behavior rather than using their misconduct to harshly judge students and set them on a trajectory with differential treatment and expectations.

Exacerbating teachers’ differential responses is the reality that many schools have limited mental health service providers. This means the responsibility for identifying mental health concerns often falls on teachers because of their close interactions with students. However, most teachers are not trained to identify mental health concerns. Mental health service providers are important because they can help students work on controlling and expressing their emotions in healthy and more socially acceptable ways. Collaborations between mental health service providers and educators could help teachers learn to differentiate between behavioral problems and mental health ones.

Cultural considerations & depression

One of the most important mental health issues to understand relative to black students is depression. Depression is one of the most prevalent and debilitating mental illnesses in the United States. Depression should not be mistaken for the typical bouts of sadness and/or irritability that subside within a few hours to a few days. In addition to sadness/irritability, common symptoms of depression include loss of interest in pleasurable activities, changes in appetite and sleep, decreased energy, difficulty concentrating, and feelings of guilt, worthlessness, and/or helplessness. However, understanding depressive symptoms is culturally oriented around white Americans. Black adolescents are often diagnosed with schizophrenia more than the more accurate diagnosis of a depressive disorder, in part due to differential symptoms and clinician bias. Instead of the standard feelings of sadness and hopelessness, black adolescents often exhibit increased irritability, anger, and aggression (Choi, Meininger, & Roberts, 2006). In addition, although not included in the criteria for depressive disorders, somatic symptoms — headaches, stomachaches, back pain, and limb pain — are among the prominent signs of depression among racial and ethnic minority adolescents (Choi & Gi Park, 2006).

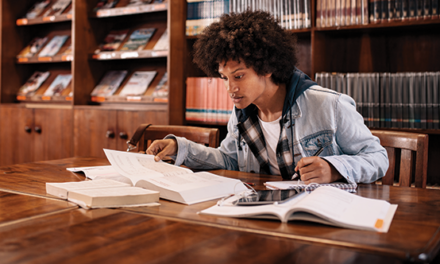

One of the authors witnessed firsthand the failure to recognize depression among black students. She worked as a clinician in a community mental health center in the Dallas (Texas) Independent School District. She indicated that the major mental health issue she saw was depression. She also noted that depression presented differently among black students and manifested in “behavioral concerns.” Black students were referred to her because of aggressive outbursts or “anger issues.” Once she started talking to them, she saw many more layers begin to unfold. She deduced that many students had not learned how to express their emotions in a healthy way. Instead, they held them in until someone pushed them over their limit, and they exploded. Teachers were often “wrapped up” in testing and academics so much that they missed students’ psychological or mental health issues or simply reduced them to behavioral concerns.

Recommendations

While black students face stressors common to all adolescents, they also disproportionately face chronic exposure to race-related stressors that adversely affect their well-being and mental health. Helping these students deal with the various concerns present during their development will require increased access to mental health services and a multisystem, culturally relevant, strengths-based approach to treatment.

Consistent with under-representation in primary care use, access to mental health services for black children is among the lowest of all ethnic groups (Holm-Hansen, 2006). Primary care physicians often identify black mental health needs but refer patients to other facilities for treatment. Since these facilities are often unfamiliar, students and their families are likely not going to follow through on referrals very often.

Communities can remove some of these common barriers to mental health service delivery by working with school districts to offer school-based mental health clinics. These clinics can include mental health professionals, typically psychologists and psychiatrists, who receive referrals from the school staff and serve students during the school day.

Teacher identification and referral concerns of black students are often misinterpreted due to teacher bias and lack of knowledge of mental illness.

Research on school-based clinics has found that they not only increase students’ mental health service use but also improve their mental health outcomes, school attendance, and grades (Ballard, Sander, & Klimes-Dougan, 2014; Rofey, Nabors, & Parkins, 2008). Although the mental health professionals in the clinic often are not school employees, being in the school expands the opportunities for consultation and advocacy. School-based clinics not only improve student outcomes, but they may have a positive effect on school outcomes as well. Mental health professionals in the clinic may offer psychoeducational workshops for teachers and staff that can help increase mental health awareness and culturally sensitive identification of potential mental health treatment needs. This is important because teacher identification and referral concerns of black students are often misinterpreted due to teacher bias and lack of knowledge of mental illness. Some of these clinics also have regular psychiatrists staffed to prescribe medicine and refer out for more intensive treatment if necessary.

Early prevention and identification programs specific to black youth are vital. The outlook of student outcomes and symptom reduction gets worse as the child gets older. To this end, it is important that school staff and teachers, especially in elementary school, implement schoolwide, evidence-based prevention and Response-to-Intervention programs to identify at-risk students early. In addition, routine pediatrician visits in the black community should be encouraged as most black adults seek help from their physician rather than a mental health professional when a psychological difficulty is present (Snowden & Pingitore, 2002). This is especially helpful given that well-child checkups now include important mental health markers (Talen, Stephens, Marik, & Buchholz, 2007).

Of course, not every school has access to community mental health clinics and mental health professionals such as psychologists and psychiatrists. Another approach to addressing mental health concerns among black students is to incorporate mental health education in the classroom. Students can learn how to respond when other students exhibit signs and symptoms of mental health challenges such as depression, anger, or anxiety. California has had success creating school-based wellness centers. In California, the Riverside Unified School District implemented several school-based wellness centers as part of a Safe Schools/Healthy Students Initiative. Qualitative data from students suggested that wellness centers positively contributed to student mental health (Guerra & Williams, 2003). However, school-based wellness centers are generally expensive. Ideally school-based wellness centers would have a first year of start-up funding followed by four or five years of implementation funding (Guerra & Williams, 2003). Several California schools have found that using students as first responders is an effective and inexpensive way of getting help for students who are more comfortable going to peers for help. This supports the utility of including topics on depression and other mental health and health issues in the curriculum to help raise overall awareness of health and wellness issues.

Lastly, ameliorating the mental health of black students will take more than just increasing access to mental health services and early identification. It also requires a critical evaluation of the practices and models being used to diagnose and treat mental health concerns. Frameworks have been established that use a positive, strengths-based, culturally appropriate approach in working with black children and adolescents. These models recognize that while black youth go through the same developmental processes as nonblack youth (e.g., puberty, identity, and maturation), culture and context play a unique role in their lives.

Strengths-based models can be used with other existing models that have consistently been found to work such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, wrap-around services, and family systems (e.g., Padesky & Mooney, 2012). These models move us away from traditional conceptualizations and treatment methods that are often deficit-based (i.e., focusing only on the risks that the student brings: low SES and test scores) and challenge practitioners to consider a child’s unique strengths, including those of resilience, family strengths, and cultural values (e.g., interdependence, spirituality, peer relationships), and build on those strengths. To this end, practitioners should consider adapting evidence-based programs to be culturally relevant to the child, as culturally adaptive mental health interventions have been found to be effective (Griner & Smith, 2006). Examples of culturally appropriate, strength-based frameworks that may be helpful in the conceptualization and treatment of black students include Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory (PVEST), Positive Youth Development (PYD), and Celebrating the Strengths of African-American Youth. Culturally adapted versions of evidence-based treatments and assessment scales are still developing and can be found with relative ease (Breland-Noble, 2012).

Conclusion

Meeting the mental health needs of black students (and all racially and ethnically diverse students) is imperative as schools are becoming more diverse. Cultural competence is a buzzword that is frequently used in mental health training to emphasize the importance of awareness, knowledge, and skills as the foundation for adequately serving diverse populations. Certainly the issues that we briefly addressed are important to understand if real progress is going to be made in serving black students. Another important and rather pragmatic step to address the mental health needs of black students is increasing the number of black mental health professionals. As psychologists and psychologists-in-training, we are well aware of the fact that blacks are under-represented in psychology (APA Center for Workforce Statistics, 2010) and likely other mental health specialties too. Black students may be hesitant to seek counseling or therapy with a white counselor or therapist because of cultural mistrust (Whaley, 2001). One of the authors observed that there was a lack of same race therapists and mental health providers for black students in her school district. Black students and their families were always shocked when they met her for the first time because she was a black therapist. She said these students and their families often said they expected to be judged by white therapists, with the implication being they felt more comfortable and at ease with her.

Black students have many mental health needs that go unaddressed. Raising awareness of issues related to race, culture, and bias is an important component of addressing black mental health. School-based mental health clinics, wellness centers, and using peers as first responders are all proven solutions to help improve the mental health of not only black students but all students.

References

Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York, NY: New Press.

American Psychological Association, Center for Workforce Studies. (2010). Demographic characteristics of APA members, 2010. Washington, DC: Author. www.apa.org/workforce/publications/10-member/table-01.pdf

Ballard, K.L., Sander, M.A., & Klimes-Dougan, B. (2014). School-related and social-emotional outcomes of providing mental health services in schools. Community Mental Health Journal, 50 (2), 145-149.

Breland-Noble, A.M. (2012). Community and treatment engagement for depressed African-American youth: The AAKOMA FFLOA pilot. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 19 (1), 41-48.

Children’s Defense Fund. (2010). Children’s Defense Fund mental health fact sheet. www.childrensdefense.org/child-research-data-publications/data/mental-health-factsheet.pdf.

Choi, H. & Gi Park, C. (2006). Understanding adolescent depression in ethnocultural context: Updated with empirical findings. Advances in Nursing Science, 29, E1-E12.

Choi, H., Meininger, J.C., & Roberts, R.E. (2006, Summer). Ethnic differences in adolescents’ mental distress, social stress, and resources. Adolescence, 41, 263-283.

Griner, D. & Smith, T.B. (2006). Culturally adapted mental health intervention: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy, 43 (4), 531-548.

Guerra, N.G. & Williams, K.R. (2003). Implementation of school-based Wellness Centers. Psychology In the Schools, 40 (5), 473-487. doi:10.1002/pits.10104

Holm-Hansen, C. (2006). Racial and ethnic disparities in children’s mental health. St. Paul, MN: Wilder Research.

Howell, E. & McFeeters, J. (2008). Children’s mental health care: Differences by race/ethnicity in urban/rural areas. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 19, 237-247.

Losen, D.J. & Orfield, G. (2002). Racial inequity in special education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Publishing Group.

Moore III, J.L., Henfield, M.S., & Owens, D. (2008). African-American males in special education: Their attitudes and perceptions toward high school counselors and school counseling services. American Behavioral Scientist, 51, 907-927. doi: 10.1177/0002764207311997

Padesky, C.A. & Mooney, K.A. (2012). Strengths-based cognitive-behavioural therapy: A four-step model to build resilience. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 19 (4), 283-290.

Rofey, D., Nabors, L., & Parkins, I.S. (2008). Effective school-based mental health interventions for urban youth. In J.A. Patterson & I.N. Lipschitz (Eds.), Psychological Counseling Research Focus (pp. 83-94). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

Skiba, R.J., Michael, R.S., Nardo, A.C., & Peterson, R.L. (2002). The color of discipline: Sources of racial and gender disproportionality in school punishment. The Urban Review, 34, 317-342. doi: 10.1023/A:1021320817372

Snowden, L.R. & Pingatore, D. (2002). Frequency and scope of mental health service delivery to African-Americans in primary care. Mental Health Services Research, 4 (3), 123-130.

Stein, G.L., Curry, J.F., Hersh, J., Breland-Noble, A., Silva, S.G., Reinecke, M.A., Jacobs, R., & March, J. (2010). Ethnic differences at the initiation of treatment for adolescent depression. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16 (2), 152-158.

Talen, M.R., Stephens, L., Marik, P., & Buchholz, M. (2007). Well-child check-up revised: An efficient protocol for assessing children’s social-emotional development. Families, Systems, Health, 25 (1), 23-35.

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). American community survey, 2011. Washington, DC: Author. www.census.gov/acs/www.

Whaley, A.L. (2001). Cultural mistrust and mental health services for African-Americans: A review and meta-analysis. The Counseling Psychologist, 29 (4), 513-531.

Wickrama, T. & Vazsonyi, A.T. (2011). School contextual experiences and longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Community Psychology, 39 (5), 566-575.

Citation: Cokley, K., Cody, B., Smith, L., Bealey, S., Miller, I.S.K., Hurst, A., Awosogba, O., Stone, S., & Jackson, S. (2014). Bridge over troubled waters. Phi Delta Kappan, 96 (4), 40-45.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Ashley Hurst

ASHLEY HURST is a counseling psychology doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin.

Brettjet Cody

BRETTJET CODY is a postdoctoral fellow with Fort Worth Independent School District.

I.S. Keino Miller

I.S. KEINO MILLER is a counseling psychology doctoral student at Indiana University, Bloomington, Ind.

Kevin Cokley

KEVIN COKLEY is director of the Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis, a professor in the Department of Educational Psychology as well as the Department of African and African Diaspora Studies, University of Texas at Austin.

Leann Smith

LEANN SMITH is a school psychology doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin.

Samuel Beasley

SAMUEL BEASLEY is a counseling psychology doctoral candidate at the University of Texas at Austin.

Stacey Jackson

STACEY JACKSON is a counseling psychology doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin.

Steven Stone

STEVEN STONE is a counseling psychology doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin.