Resource-stretched schools can ensure comprehensive mental health care for students by creating partnerships with community-based service providers.

No single strategy or service can meet the mental health needs of all students. Schools are learning to use their internal staff and resources more effectively to provide a comprehensive range of services and in some cases augment and enhance them through school-community partnerships.

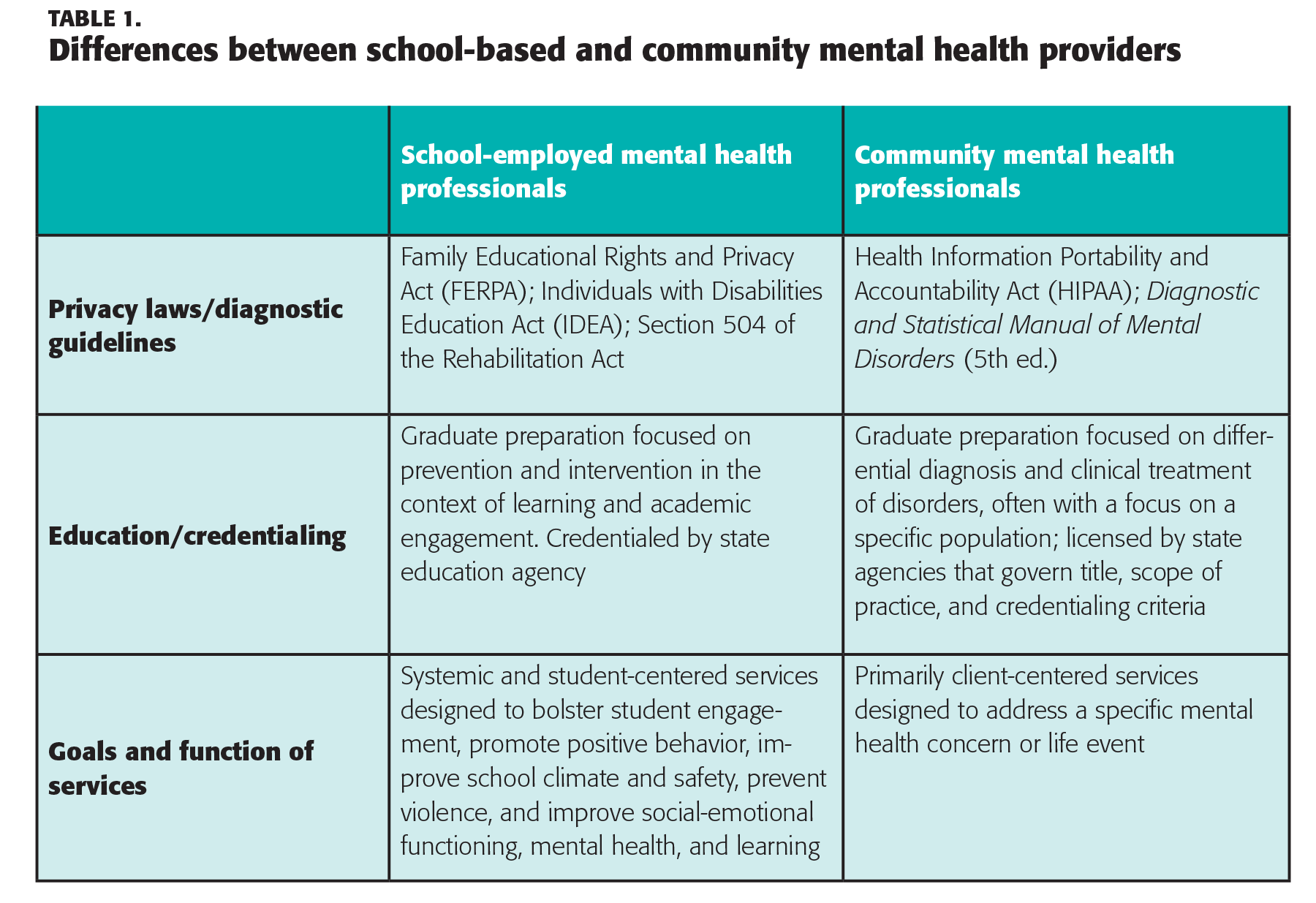

Providing student and family access to a full continuum of mental health services requires collaboration between community providers or outside agencies and school-employed mental health professionals — school psychologists, counselors, social workers, and nurses. These two groups of professionals play a distinct, complementary role in school-based service delivery. Effectively integrating school and community mental health services can be challenging due to some distinct differences between school-employed and community mental health professionals (see Table 1). Understanding these differences can help facilitate a positive dialogue about how to best integrate certain community health services into existing school systems.

School-employed mental health professionals can provide a range of services to improve school climate and safety, remove individual barriers to learning, and ensure that students are engaged, attentive, and available for learning. These professionals are part of the school’s fabric and can serve all children and families. However, inadequate staffing often means they must focus on students with the most severe needs and limit services to others. Supporting students while meeting legal mandates for students receiving services under IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) leaves fewer opportunities for prevention and early intervention services.

Providing student and family access to a full continuum of mental health services requires collaboration between communities and schools.

Even in districts with sufficient staff, few schools have the capacity to meet the full continuum of student mental health needs alone. In many partnerships, community mental health professionals help fill this gap by providing services to students with the most significant needs, many of whom have a formal mental health diagnosis. While school-employed mental health professionals are qualified to provide intensive counseling services for students, they often don’t have the time to do so. Community partners fill a critical need while giving school-employed professionals more time for critical prevention and early intervention services to students during the school day. Additionally, students with intense needs have access to the community supports after school and on weekends.

Building a strong partnership foundation

Each partnership is unique based on the specific needs of schools and districts. In some cases, like the Boston Public Schools, community partnerships are a district-led endeavor; in other cases, an individual school initiates a partnership with a community agency. School-community partnerships don’t follow a standard model, but six key elements can result in a more integrated and efficient service delivery system:

- A leadership team comprised of school and community stakeholders;

- Ongoing assets and needs assessments;

- A designated service coordinator;

- Clear expectations and shared accountability systems for community providers;

- Ongoing professional development; and

- Regular evaluation of effectiveness (Roche & Vaillancourt, in press).

This list is not exhaustive, as there are certainly other components that improve the effectiveness of school-community partnerships, including family involvement. But these six elements form the necessary foundation of effective school community partnerships upon which schools can build.

Key elements of school-community partnerships

#1. A diverse leadership team

At the school and the district level, the leadership team guides the formation, implementation, and evaluation of the partnership(s). This team should include representatives from the school and the community. A leadership team in which all members are committed to the work helps ensure that the partnership will be truly collaborative and will supplement, not duplicate, services already available at the school.

Boston Public Schools (BPS) is a member of the School-Based Mental Health Collaborative (SBMHC) that brings together representatives from community mental health agencies and the school district to coordinate and align school-based and community mental health services. Historically, BPS had limited leadership with this group, which resulted in inconsistent and inefficient school-based mental health service delivery. After a leadership change at BPS, Andria Amador (one of the authors), became assistant director of behavioral health services and quickly recognized that a collaboration between BPS and community-based service providers would yield more consistent and effective school-based mental health services. Amador believed the school district had to be a leader in this endeavor. The district has 127 schools serving 57,000 students. Currently, the district partners with 13 community agencies who provide services in 90 schools, reaching about 3,500 students. A few community partners who were used to operating independently were resistant. However, after considerable discussion, most realized this shift would improve mental health services delivery for BPS students. Realigning SMBHC leadership has improved both stakeholder engagement and the alignment of school and community resources and also increased collaboration among school and community mental health professionals.

Having a building-level leadership team also is helpful. Cincinnati Public Schools makes school-community partnerships a district priority. But each school manages its own school-community partnerships and involves a diverse group of representatives from the school and community. Each school determines the leadership team’s responsibilities based on the partnership goals (discussed below), but the leadership team should represent all stakeholders and include at least one school-employed mental health professional.

#2. Assets, needs assessment, and resource mapping

Schools should examine their assets and needs before determining what community resources may be needed.

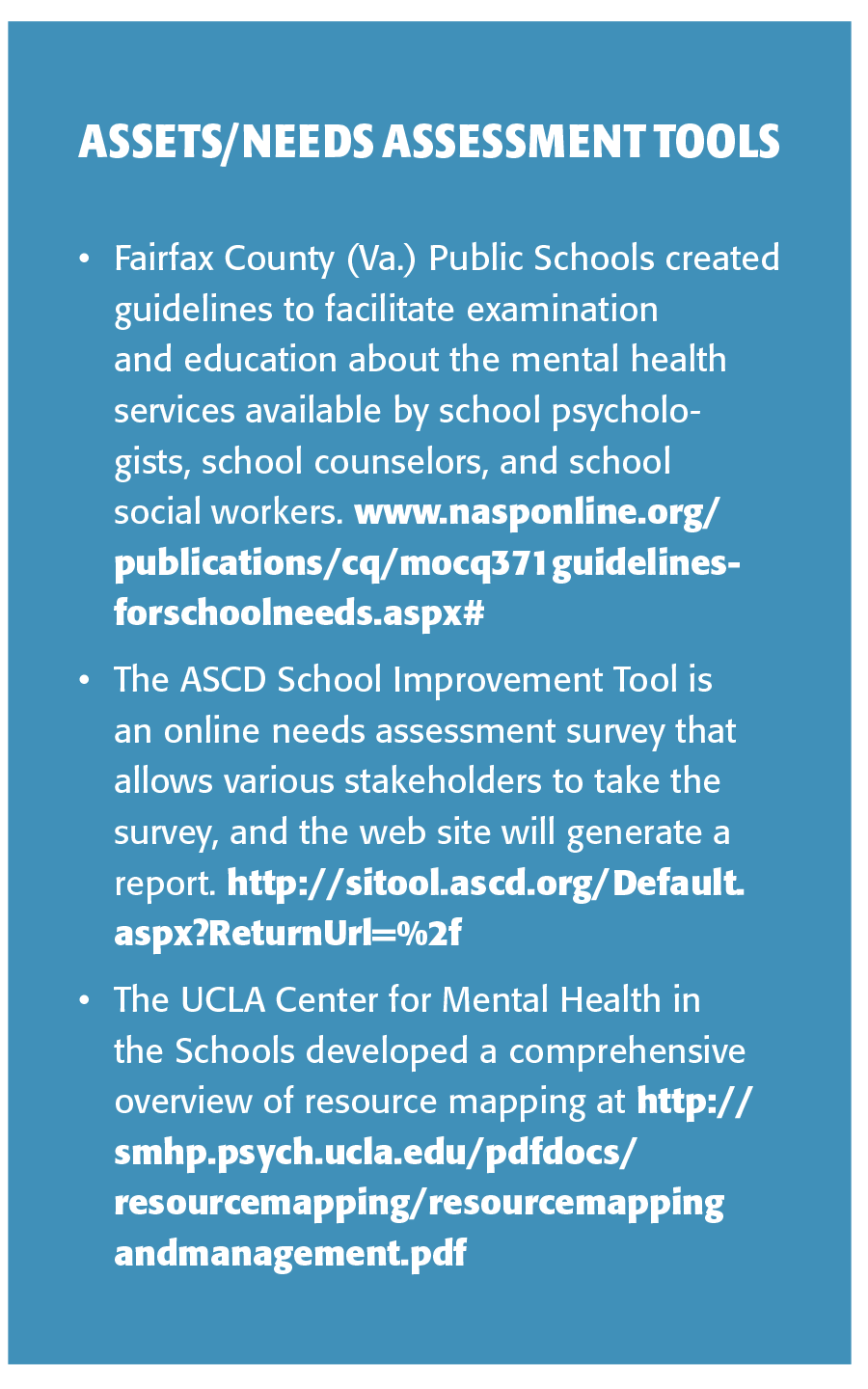

Schools should examine their assets and needs before determining what community resources may be needed. A first step is ensuring that relevant school personnel are being used appropriately and to the best purpose given their skill set. In addition to ratios, sometimes role definitions or the framework for service delivery can impede full service delivery. This makes it important to examine the services being offered, staff skill sets, and students being served, and how that corresponds to the identified needs of students in the district. While time-consuming, resource mapping can show gaps in service delivery and help schools pick a partner that can enhance existing services and help meet identified needs. A number of publicly available resources can help schools examine their assets and needs. (See Assets/Needs Assessment Tools below.)

#3. Designated service coordinator

The service coordinator acts as the point person between community agencies and the school; he or she facilitates effective communication between all parties and helps compile necessary data for the leadership team to routinely review. A designated coordinator is particularly important if a school or district has more than one partner providing services in the school. When the school has a partnership with a single agency to support student mental health, a full-time coordinator may not be necessary.

#4. Clear expectations, shared accountability

School-employed and community mental health professionals must understand who provides services so this can be clearly communicated to parents and school staff. In the beginning years of the Boston Public Schools mental health collaborative, the partnership had no protocol to guide the work and information sharing. As a result, parents, school staff, and community agencies were confused about how to refer a student for services, what information could be shared and with whom, which entity was responsible for meeting the needs of various groups of students, and what services were being provided. To ease confusion, the team developed Standards of Practice guidelines for effective and integrated delivery of school-based mental health services. All persons delivering services participated in a district-led training on policies and procedures for crisis intervention, mental health services, and key differences between working as a mental health provider in a school vs. the community.

Specific role delineation between school and community mental health professionals will vary based on each school’s needs but is crucial to maximizing effectiveness. Boston Public Schools uses a multi-tiered system of support to provide universal (Tier 1), secondary (Tier 2), and tertiary (Tier 3) interventions to students. School-employed professionals are available to all students and provide services in each tier. School psychologists receive all referrals for students’ academic and behavioral issues, and school-employed professionals provide all services included in a student’s Individualized Education Program. Community mental health professionals work with students who need more intensive support that goes beyond what can be provided during the school day. This includes intensive, Tier 3 interventions and wraparound care from other community-based providers.

In addition to having clear expectations and role delineation, the school and the community provider(s) must share accountability for student outcomes. One way to ensure this is to incorporate the goals of the community partnership into the school improvement plan with specific, measurable outcomes for school and community providers.

#5. Ongoing professional development

All professionals involved in school-based mental health service delivery should have high-quality professional development. To make the most of limited time and resources, professional development should be directly related to the identified needs of the school and mental health practitioners. Including community providers in professional development opportunities can help them understand the various systems at the school and form better relationships with school staff. In many cases, the school-employed mental health professionals or community partners can provide the professional development, which can help reduce or eliminate costs.

#6. Regular evaluation of effectiveness

In evaluating the partnership’s effectiveness, participants should consider predetermined and agreed-upon goals. In conjunction with examining school and student-level data, seeking input from staff, students, and families can be helpful. In one school, a mid-year survey revealed parents’ dissatisfaction with communication about availability of school-based mental health services and how to access them. Although students who were receiving services were making progress, the school realized it needed to improve communication about how to access mental health services.

Challenges

Schools and districts must acknowledge and address some common challenges:

- Building trust and avoiding turf wars;

- Sharing information in a timely manner with the appropriate people; and

- Planning for long-term sustainability.

Building trust

No one wants to admit it, but there can be a lack of trust between school-employed and community mental health professionals. Tensions are most often caused by lack of understanding of each other’s qualifications, terminology, service delivery models, and normal processes and perspective, all of which can lead to defensiveness. Clearly delineating the value of staff’s school-oriented training and role and community providers’ scope of services and resources can help ease misunderstandings and related distrust. Staying focused on meeting children’s needs also can help all parties view each other as partners and allies, while also respecting each other’s unique training and perspective. This takes time and requires collaboration and transparency between school and community partners. There is more than enough work for everyone, and the focus should always be on improving the mental health of children and youth.

Information sharing

Perhaps one of the most challenging issues is understanding the intersection of FERPA and HIPAA. These laws protect the privacy of educational records and health information, respectively. Yet they create challenges in determining what information can legally be shared between school and community mental health professionals. Schools and districts have specific procedures that, with parental permission, allow school employees to exchange information with a child’s doctor or other health professional not affiliated with the schools. In many cases, there are narrow parameters about what information can be shared, and the parent can rescind permission at any time. However, navigating information sharing in the context of a partnership is largely uncharted territory. How much of a child’s education record should be made available to the community mental health provider? What information is the community provider legally able to share with school officials when a student is receiving services? These questions are not easily answered.

A true collaborative partnership requires clear guidelines regarding how and what information can be shared and how to clearly communicate those guidelines to families. The U.S. Department of Education and the Department of Health and Human Services offer guidance to help answer questions regarding student education records and student health records at www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/coveredentities/hipaaferpajointguide.pdf. Additionally, The Coalition for Community Schools (www.communityschools.org) has resources and examples of information-sharing protocols used by districts around the country. Before entering into an information-sharing agreement, consult legal counsel to ensure that all providers are following the mandates included in HIPAA, FERPA, and other privacy laws in your state and district.

A plan for long-term sustainability

There is currently a shortage of both school-employed and community-employed mental health professionals, along with limited financial resources dedicated to schools. Schools need to ensure they are using their existing staff in the most effective way and to seek creative ways to fund personnel to help supplement existing school-based services that includes both district and outside funds (Blank et al., 2010). Some districts mistakenly consider outsourcing all mental health services to community providers to save money. This approach runs contrary to long-term sustainability and availability of services. Many community professionals are funded via third-party insurance reimbursement, which typically requires a specific diagnosis. Requiring a diagnosis potentially precludes mental health services for students with less severe needs, or it can cause clinicians to apply an unnecessary diagnosis for reimbursement purposes. Improving ratios of school-employed mental health professionals allows all students to access appropriate services, including prevention and early intervention.

Conclusion

Building effective school-community partnerships requires recognition of barriers along with time and commitment from school districts and community agencies to overcome those barriers. Addressing the challenges while also building partnerships may be overwhelming, but this work is essential for ensuring effective outcomes for children and youth.

References

Blank, M., Jacobson, R., Melavile, A., & Pearson, S. (2010). Financing community schools: Leveraging resources to support student success. Washington, DC: Coalition for Community Schools. www.communityschools.org/assets/1/AssetManager/finance-paper.pdf

Roche, M. & Vaillancourt, K. (in press). Key elements of effective school community partnerships to address student health and wellness. Washington, DC: Coalition for Community Schools

Citation: Vaillancourt, K. & Amador, A. (2014). School-community alliances enhance mental health services. Phi Delta Kappan, 96 (4), 57-62.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Andria Amador

ANDRIA AMADOR is a school psychologist and assistant director of behavioral health services for Boston Public Schools.

Kelly Vaillancourt

KELLY VAILLANCOURT is a school psychologist and director of government relations for the National Association of School Psychologists, Bethesda, Md.