Research tells us that children’s social-emotional development can propel learning. A new program embeds that research into classroom management strategies that improve teaching and learning.

Research tells us that children’s social-emotional development can propel learning. A new program embeds that research into classroom management strategies that improve teaching and learning.

“By incorporating . . . strategies into daily routines, my students now have a means to express their feelings and act appropriately when faced with a situation that involves others. My students now are able to use those strategies to remind each other and me to ‘cool down,’ ‘be patient,’ ‘count to five,’ ‘take turns,’ etc.”

“I just realized the more you use it, the more they [kids] use it as well.”

— Teachers using a new, self-regulation strategy

Classroom management is central to teacher practice. Successful student learning depends on a teacher’s ability to manage the group as a whole — keeping the attention of 30 or more students, redirecting negative or distracting behavior, and continually assessing the pulse of the room to optimize student motivation and engagement. Despite the size and importance of the task, classroom management is perhaps the most underdeveloped area of teacher education. Rarely do new teachers feel that their classroom management skills are a match for their students.

But what is effective classroom management? In our view, two items are essential: Teachers need knowledge about children’s behavior and development, and they need familiarity and practice with strategies that have been proven to work.

Strategies embedded in most high-quality, social-emotional learning programs can provide teachers with both of these things.

Four principles

Classroom management is not about controlling students or demanding perfect behavior. Instead, effective management is about supporting students to manage themselves throughout daily learning and activities. Part of the teacher’s role is to give students the tools they need to interact with and meet the demands of the social and instructional environment of school. Different activities and different children will require different types of support, so teachers need a diverse set of strategies. Effective classroom management will look different in different grade levels. But across all classrooms and grade levels, four principles of effective management are constant.

- Effective classroom management is based in planning and preparation.

Effective classroom managers map the day’s learning activities as well as transitions between activities and think deliberately about what is likely to be difficult for specific individuals, groups, or the class as a whole. Teachers who make time for such management-oriented planning are less likely to be caught off guard when things go awry, and they’re more likely to have a strategy prepared in advance and to implement it quickly, enabling them to steer students back on track when disruptions occur.

Disruptions are inevitable in every classroom. This type of planning acknowledges that and enables teachers to handle problems in responsive, not reactive, ways. Responsive classroom management is more likely to be thoughtful, concrete, consistent, and implemented in a calm and supportive way. In contrast, reactive management can be angry, punitive, inconsistent or unclear, and tends to escalate the problem behavior (Lesaux, Jones, Russ, & Kane, 2014).

Responsive classroom management is more likely to be thoughtful, concrete, consistent, and implemented in a calm and supportive way. In contrast, reactive management can be angry, punitive, inconsistent or unclear, and tends to escalate the problem behavior.

- Effective classroom management is an extension of the quality of relationships in the room (Marzano, 2003).

Teachers who establish and maintain high-quality, trusting relationships with students can draw on their history of positive interactions in order to address classroom management challenges as they arise. In contrast, teachers regularly engaged in conflict with students are less able to respond effectively to classroom disruptions. This is especially true for unanticipated problems that demand “on the fly” action from teachers. High-quality relationships are characterized by warmth and responsiveness to student needs on one hand and by clear boundaries and consistent consequences on the other hand. Striking the right balance between warmth and discipline is a common challenge. In some settings, discipline looks like overcontrol with too much emphasis on rigid rules, which can lead teachers to be inflexible and unresponsive to student needs. This approach offers students no opportunity for building skills in self-management or autonomy, and it represents an unreasonable expectation of perfect behavior from students. In other settings, there may be an emphasis on warmth or autonomy, but the boundaries are not consistently enforced, or they’re missing altogether. Teacher-student relationships that balance these two needs provide the best foundation for effective classroom management.

- Effective classroom management is embedded in the environment.

A well-managed classroom includes direct material supports as well as a consistent set of routines and structures throughout the day. Posters, charts, or a calm-down corner are examples of material support; they remind students of classroom expectations and provide visual or physical tools to help students achieve them. Routines might include a strategy to help students transition between activities, such as a song or signal. Structures might include a morning meeting or weekly celebration for positive behavior. Together, these features organize and define appropriate behavior at different times of the day; they make the classroom predictable. Importantly, supports that are embedded in the environment help students manage themselves by reinforcing expectations and promoting positive behavior even when the teacher is unavailable.

- Effective classroom management includes ongoing processes of observation and documentation.

Finally, classrooms are fast-paced and constantly changing; what works one day might not work the next. Teachers need to regularly reassess management strategies and adapt as needed. Disruptive behavior can test adults’ patience and make it difficult to think clearly in the heat of the moment. Documentation helps educators notice patterns and better anticipate and address recurring problems. Careful observation and documentation — writing down what happened, what you did/said, and how students responded — lets teachers continually reflect on and improve their interactions with students and their general plan for classroom management.

A central theme across all four principles is that effective classroom management is not about reaction but about prevention and building skills. When teachers adopt these principles, they create an environment that enables children to manage their own behavior with increasing independence.

Social-emotional learning

Classroom management and social-emotional learning are related in a number of ways. Social-emotional skills are a foundation for children’s positive behavior in school (Boyd et al., 2005; Denham, 2006; Raver, 2002). Key social-emotional skills include focusing, listening attentively, following directions, managing emotions, dealing with conflicts, and working cooperatively with peers (Jones & Bouffard, 2013). Children who are strong in these skill areas are less disruptive and better able to take advantage of classroom instruction. Children who struggle in these areas are more likely to be off-task, engage in conflicts with peers or adults, and minimize learning time for themselves and others. Teachers may feel that these children undermine their efforts to manage the classroom as a whole.

Teachers also must use their own social-emotional skills to establish high-quality relationships with students (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009; Jones, Bouffard, & Weissbourd, 2013). Providing teachers — especially new teachers — with concrete social-emotional strategies can enhance their capacity for positive interactions and effective communication with students. Furthermore, when all adults in the school community use the same strategies, children experience predictability in the quality of interactions throughout the school day, which promotes their understanding and use of appropriate behavior.

In our own work, we find that social-emotional development is a helpful lens for approaching children’s behavior in new and productive ways. Rather than blaming children or becoming frustrated by “bad behavior,” we encourage teachers to reframe disruptive behavior and other classroom management challenges as teaching and learning opportunities in the social-emotional domain.

Research indicates that certain social-emotional skills emerge earlier than others and lay the foundation for more complex skills. For example, executive functions develop rapidly during early childhood, helping young students begin to focus their attention, ignore distractions, remember simple directions, and manage their behavior according to social norms (Center on the Developing Child, 2011). This is an ideal time to support students with simple strategies to manage attention and remember classroom rules, such as “turn on your listening ears for story time.” Young students need reminders and support from adults in order to be successful at tasks that use these newly emerging skills. During middle childhood, students develop the ability to engage in more complex social-emotional behaviors such as thinking about the consequences of their actions, anticipating or resolving conflicts with peers, and participating successfully in teamwork and group activities (Eisenberg, Fabes, & Spinrad, 2006; Saarni, Campos, Camras, & Witherington, 2007). Explicitly considering children’s social-emotional development can help teachers establish reasonable, age-appropriate expectations for classroom behavior and can help teachers identify which skills and strategies are most relevant for each age group.

Effective classroom management is not about reaction but about prevention and building skills.

SECURe strategies

Drawing upon and extending recent research, our team of researchers and practitioners developed a new school-based intervention in social-emotional learning called SECURe — Social, Emotional, and Cognitive Understanding and Regulation in education (Bailey et al., 2012). SECURe is grounded in supporting the development of children’s executive functions and regulatory skills, and aims to build teacher skills via improved instructional practices, organizational and management practices, and warmth and responsiveness. The goal of SECURe is to develop “a community of self-regulated learners.” At its core, SECURe is an interconnected set of strategies — professional development and support, classroom lessons, and daily structures and routines — that build and sustain adult and child skills to support learning. SECURe is designed to be implemented across grades preK-5 and used throughout the school in classrooms, hallways, gym, and cafeteria alike, and in academic content. All students, teachers, specialists, lunchroom monitors, and other school staff are trained in a common set of strategies designed to promote a well-regulated classroom and school environment.

SECURe targets skills in three broad areas: cognitive regulation/executive function, emotion processes, and interpersonal skills. Within each area, students are taught skills through weekly (grades 1-5) or twice weekly (preK-K) lessons. SECURe lessons use high-quality children’s literature, songs, games, role-play with puppets, art activities, and short videos to introduce new skills and concepts. For example, in a preK lesson, students read a Curious George book to identify basic emotions and then learn a strategy called I Messages to tell other people how they’re feeling: “I feel mad because you took my crayon.” In another lesson, students watch a short cartoon about a penguin that gets easily frustrated, and then they practice a strategy for calming down when they feel upset or angry. The strategy — Stop and Stay Cool — includes basic coping mechanisms such as counting slowly to five, taking deep breaths, and giving yourself a hug. Classroom materials like the Feelings Tree (a word wall for emotions-related vocabulary), Feelings Faces picture cards, I Messages sentence strip, and Stop and Stay Cool posters help students remember strategies and use them as situations arise throughout the day. Visual materials are included in classrooms but also in the lunchroom, hallways, gym, music room, and principal’s office. When an adult sees that a student is starting to “lose his cool,” the adult can help the student walk through the steps or use an I Message to talk about what happened.

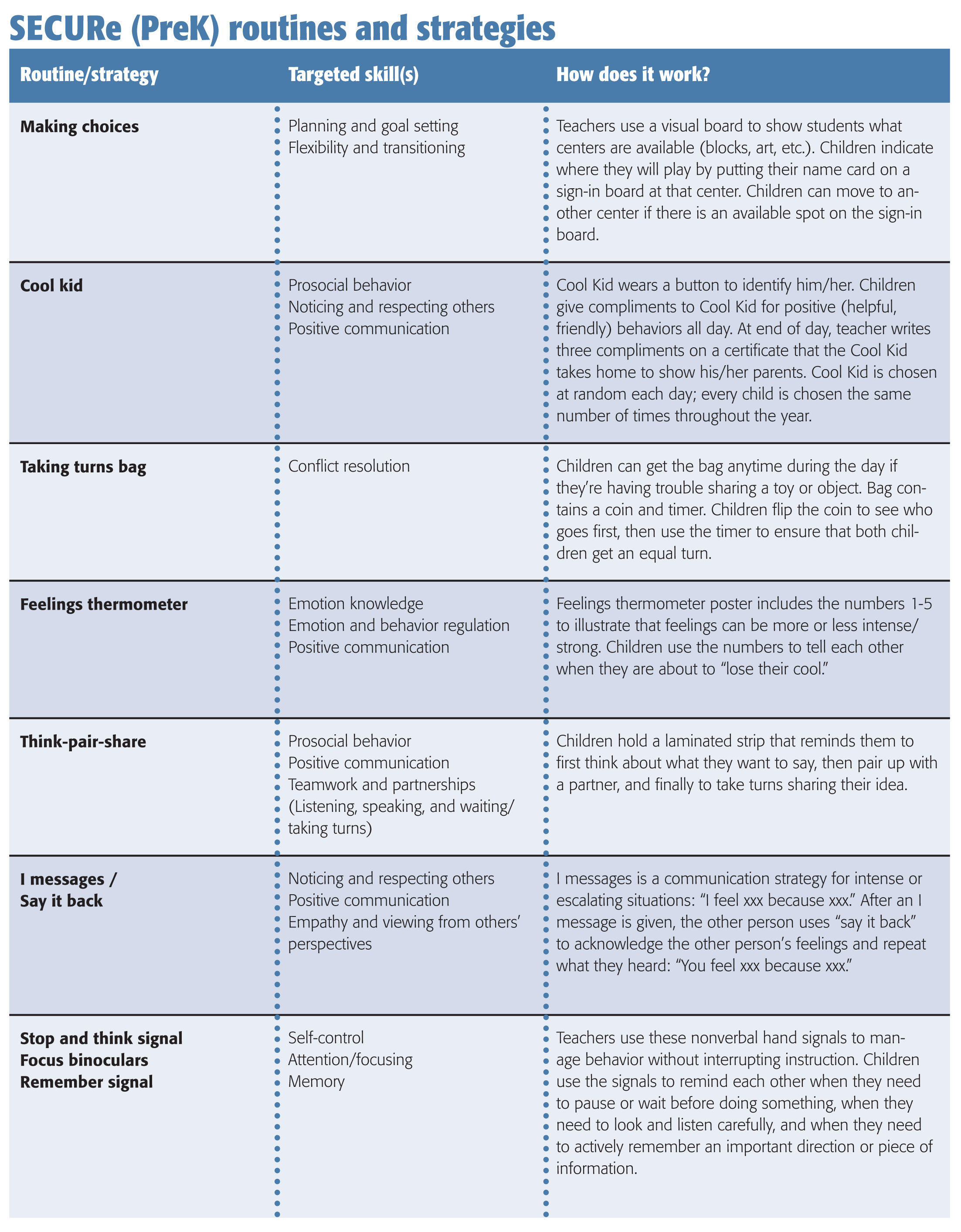

The second component of SECURe includes daily structures and routines that provide opportunities to practice skills in recurring interactions and relationship-building activities. In SECURe PreK, daily routines include Pocket Points, Brain Games, Making Choices, and Cool Kid. Pocket Points are a strategy to promote positive behavior in the classroom. Students can earn a Pocket Point when they do something kind or helpful: The teacher gives the student a brightly colored chip, and she puts the chip in a classroom jar. At the end of each day, Pocket Points are counted and if a certain number have been earned, the class gets a reward or special privilege.

Brain Games are also used flexibly as a skill-building and classroom management tool. Brain Games are a set of fun, motivating games that require students to use their cognitive regulation and executive function skills — including Stop and Think Power, Focus Power, and Remember Power. For example, in the Freeze Game, students dance around to music in a circle. Each time the music stops, students use their Stop and Think Power to stand completely still, waiting for the music to start again. Brain Games include discussion questions for teachers to facilitate with students: What helped you be good at this game? How can you use Stop and Think Power to help you in school today? Teachers might remind students to use Stop and Think on the playground while waiting for a turn on the slide or in the classroom to raise a hand instead of shouting an answer. Students play Brain Games at a specific time each day, but teachers also use the games during transitions or other down time. SECURe routines organize the day around a predictable set of activities that help students continue to build skills in daily and ongoing interactions. (See table below).

Other SECURe strategies designed to promote positive interactions include the Taking Turns Bag, Feelings Thermometer, Focus Binoculars, Think-Pair-Share, and Say It Back, among others. As with I Messages and Stop and Stay Cool Steps, students and teachers can use these strategies to address a variety of classroom challenges. They support adults to be warm and responsive and also provide language for dealing with conflicts or disruptions when they arise.

What we have learned

During the 2012-13 academic year, SECURe PreK was piloted in a large, urban public school district that primarily serves students from low-income and non-English speaking homes. We located our pilot work with SECURe in vulnerable contexts because there is a growing body of research documenting links between the stresses associated with poverty and challenges for children with self-regulation and behavior. Funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the pilot study included 12 Head Start classrooms (morning and afternoon classes with six lead teachers) embedded within two elementary schools in the district. Forty-two additional classrooms (including Head Start as well as a tuition-based preschool) from the remaining six schools in the district were also included in the study. The 12 SECURe classrooms each received training, curriculum, classroom materials, school-year PD and coaching, technical assistance for SECURe PreK. The other 42 classrooms continued their standard practice. Implementation of SECURe PreK included daily use of the structures and routines as described above, and twice weekly lessons that each lasted about 15 minutes.

Focus groups conducted with teachers in the fall and spring suggested that individual teachers varied in the degree to which they embraced different SECURe strategies, largely based on the challenges they observed and were struggling with in their classrooms. For example, in a classroom that was described by the preschool program director as having an unusually challenging group of students, the teacher used the SECURe Feelings Tree to create her own daily routine. Each day after returning from recess, the teacher organized children in a circle on the rug to discuss what went well and what didn’t go well on the playground. The teacher used the SECURe Feelings Tree, Feelings Faces picture cards, and I Messages sentence strip to encourage students to talk about what happened, how they felt about it, and what could be done in the future to create a more friendly and successful playground time. This teacher said using the SECURe strategies helped manage what was otherwise a difficult and chaotic time of day — the return from recess. She spent five to 10 minutes in this “feelings circle” each day, in addition to the prescribed program activities. This time was well spent, she said, because it enabled children to calm down, address problems and hurt feelings immediately, and then return to general instruction with everyone ready to focus on learning. At the end of the year, the program director praised her for turning around an otherwise unruly classroom.

In another classroom, the teacher put less emphasis on emotion-related strategies but more on cognitive regulation skills, playing Brain Games multiple times per day and frequently using strategies like Stop and Think and Think Alouds. Stop and Think is a reminder for students to slow down and think before they act; it builds self-control and supports students to be planful and reflective about their behavior. Think Alouds are a process by which teachers narrate their own thoughts or feelings. Many cognitive and social-emotional skills involve things we say internally to ourselves in order to concentrate, maintain control, choose appropriate behavior, etc. Think Alouds make this mental activity explicit so children can build understanding as well as metacognition skills. In end-of-year focus groups, this teacher commented that SECURe helped her “think about my own thinking.” Thus, it appears that individual teachers may adopt specific program components with ease, and find their own way of integrating SECURe strategies into classroom management and instructional practices. We suggest this is ideal — that teachers are given a large toolkit of resources to address potential classroom management challenges and are able to choose the best tool to fit each situation, each teacher’s style and preferences, and the needs of particular groups of students. Our implementation data and written feedback from teachers confirms the power of routines and structures as management tools. For example, one teacher wrote, “Overall, I really enjoyed using SECURe because I do feel it helped me with behavior management. I think SECURe gives students words to express themselves in appropriate ways. It gives them ways to control their feelings and learn how to deal with them.”

From this small, nonrandomized sample, the SECURe research team also collected data from children about their social-emotional skills and behaviors and from the district on classroom quality and student functioning (Jones & Bailey, 2014). Overall, we found positive effects of SECURe on classroom quality with classrooms observed to be generally more positive, emotionally supportive, and well-managed. In addition, by the end of the year, SECURe classrooms on average had more children rated as “meeting benchmarks” in the cognitive, literacy, and social-emotional domains of the Teaching Strategies Gold instrument (Jones & Bailey, 2014).

Another, larger pilot study of the effects of SECURe in K-3 classrooms found similar results (Jacob, Jones, & Morrison, under review). That study, which involved over 4,000 students in six schools (half of which implemented SECURe and half that did not), demonstrated that the program increased students’ attention skills and reduced their impulsive behavior, and also had a positive effect on literacy skills, especially among the lowest-achieving students in the sample.

Most teachers struggle with classroom management at some point in their career, some teachers struggle with it indefinitely, and many teachers leave the profession because of the daily stress and difficulty associated with managing children and classrooms. By implementing management strategies that actively build children’s social-emotional and self-regulatory skills, teachers maximize their management efforts and increase the likelihood that students will be able to respond successfully to their requests for on-task behavior. By providing concrete and age-appropriate strategies to help students learn to manage their attention, feelings, and behavior successfully, educators can support social-emotional development while enhancing classroom management and instruction. Addressing the needs of teachers around classroom management can have a significant effect on children’s learning and behavior outcomes as well as teacher quality, job satisfaction, and retention.

References

Bailey, R., Jones, S.M., Jacob, R., Madden, N., & Phillips, D. (2012). Social, emotional, and cognitive understanding and regulation in education (SECURe): Preschool program manual and curricula. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Boyd, J., Barnett, W.S., Bodrova, E., Leong, D.J., & Gomby, D. (2005). Promoting children’s social and emotional development through preschool education (NIEER policy report). Piscataway Township, NJ: National Institute for Early Education.

Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2011). Building the brain’s “air traffic control” system: How early experiences shape the development of executive function. (Working Paper no. 11.) www.developingchild.harvard.edu

Denham, S.A. (2006). Social-emotional competence as support for school readiness: What is it and how do we assess it? Early Education and Development, 17 (1), 57-89.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R.A., & Spinrad, T.L. (2006). Prosocial development. In W. Damon, R.M. Lerner, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.) Handbook of child psychology (6th ed., Vol. 3) Social, emotional, and personality development. New York, NY: Wiley.

Jacob, R., Jones, S.M. & Morrison, F. (Under review). Evaluating the impact of a self-regulation intervention (SECURe) on self-regulation and achievement. Early Childhood Research Quarterly.

Jennings, P.A. & Greenberg, M.T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79 (1), 491-525.

Jones, S.M. & Bailey, R. (2014, March). Preliminary impacts of the SECURe PreK on child and classroom-level outcomes. Paper presented at the meeting of the Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness, Washington, D.C.

Jones, S.M. & Bouffard, S.M. (2013). Social and emotional learning in schools: From programs to strategies. Social Policy Report, 26 (4).

Jones, S.M., Bouffard, S.M., & Weissbourd, R. (2013). Educators’ social and emotional skills vital to learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 94 (8), 62-65.

Lesaux, N., Jones, S.M., Russ, J., & Kane, R. (2014). The R2 educator. Lead Early Educators for Success (Brief Series). http://isites.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do?keyword=lesaux&pageid=icb.page660137

Marzano, R.J. (2003). Classroom management that works. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Raver, C.C. (2002). Emotions matter: Making the case for the role of young children’s emotional development for early school readiness. Social Policy Report, 16 (3).

Saarni, C., Campos, J.J., Camras, L.A., & Witherington, D. (2007). Emotional development: Action, communication, and understanding. Handbook of Child Psychology (6th ed., Vol. 3). New York, NY: Wiley.

CITATION: Jones, S.M., Bailey, R., & Jacob, R. (2014). Social-emotional learning is essential to classroom management. Phi Delta Kappan, 96 (2), 19-24.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Rebecca Bailey

REBECCA BAILEY is assistant director of the EASEL Lab at the Harvard Graduate School of Education in Cambridge, Mass.

Robin Jacob

ROBIN JACOB is an assistant research professor at the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Stephanie M. Jones

STEPHANIE M. JONES is the Gerald S. Lesser Professor of Early Childhood Development at the Harvard Graduate School of Education in Cambridge, Mass.