Why we should reconsider the 1968 conflict between the Ocean Hill-Brownsville community and the New York City teachers union

By Alexander Russo

Fifty years ago this month, New York City’s United Federation of Teachers (UFT) was deeply embroiled in a dispute with one of 32 community school districts that made up the massive New York City school system.

Under a pilot school decentralization project called “community control,” local administrators in the predominately African-American and Puerto Rican community of Ocean Hill-Brownsville had dismissed 19 educators from their schools and told them to report for reassignment at the central Board of Education.

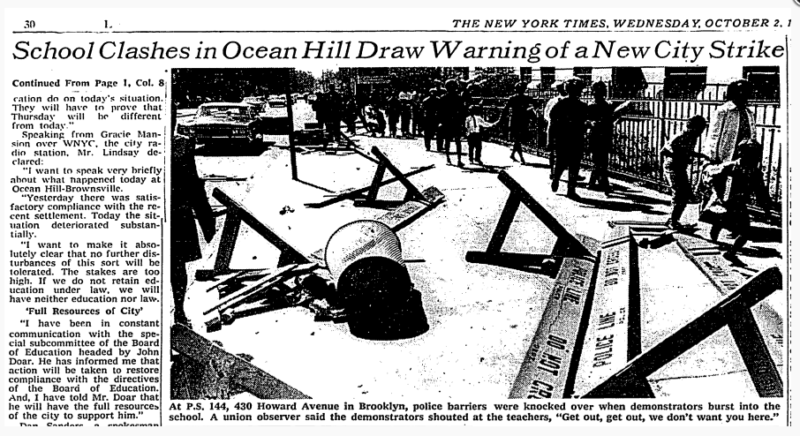

In response, the union — then predominantly white and largely Jewish — conducted a series of three strikes that shut down the million-student New York City school system. After a total of 36 days, the strike ended with the reinstatement of the teachers at their schools and the dissolution of community control.

There have been a handful of remembrances this year, including a long piece in Commentary and a two-part WNYC public radio series that aired last week. And for good reason. The conflict between the union and the community control board is an enormously important moment in the history of education in the United States. It was “the most infamous and largest teachers strike in American history,” according to journalist Dana Goldstein in her 2014 book, “The Teacher Wars.”

But the piece that has attracted my attention the most has been “The UFT’s Opposition to the Community Control Movement,” published as part of a series of retrospectives in the socialist quarterly Jacobin.

Written by City University of New York professor Steve Brier, the piece raises a number of questions about what really happened all those years ago – and how the media depicted the events.

In his piece and subsequent phone interviews, Brier says that the events of 1968 don’t actually fit the usual description of a conventional teachers strike. “When people hear the word ‘strike’ they assume it’s a labor issue,” Brier told me. “But that wasn’t the case here.” What happened in New York in 1968 was, according to Brier, “a political strike against the idea of community control.” And the outcome was partly the product of deeply flawed journalism.

Other experts and journalists disagree with Brier or don’t go as far as he does in advocating for a full-scale reconsideration of events. However, Brier is not entirely alone in taking a dramatically different view of what happened. Ocean Hill-Brownsville “should be spoken of in the way historians speak of Gettysburg, or Stonewall, or Kent State,” writes education advocate Chris Stewart on his site, Citizen Education. “It was a $7.8 billion strike against black communal power in education and an affront to our 400-year petition for material freedom to self-govern.”

From this perspective, what happened in 1968 might not even correctly be described as a teachers strike. Through the eyes of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville community, what happened in 1968 was an attempted revolt, a fledgling independence movement — a thwarted insurrection. But it’s rarely described from that point of view.

Related coverage: Oklahoma teacher walkout coverage was abundant, though marred by partisan politics

New York Times coverage from 1968

Fifty years ago, the New York schools were governed by a central school board headquartered at the infamous 110 Livingston Street building in downtown Brooklyn. The system was considered to be a sclerotic bureaucracy that couldn’t seem to get anything done. The arrival of unionization meant that teachers were no longer entirely under the thumb of principals and salaries were based on certifications and seniority.

But the system wasn’t effective at serving students of color, whose numbers were growing year by year. And efforts to promote integration — including a massive protest and school boycott in 1964 — had failed to produce meaningful action. Community control was piloted in three parts of the city to give local leaders and parents a stronger say in how neighborhood schools were being run.

Strikes were more common in those days, and conflict with the union wasn’t new to Ocean Hill-Brownsville. The year before, community leaders had objected to a UFT strike focused on the union’s desire to allow teachers to remove from class students who they said had been “disruptive.”

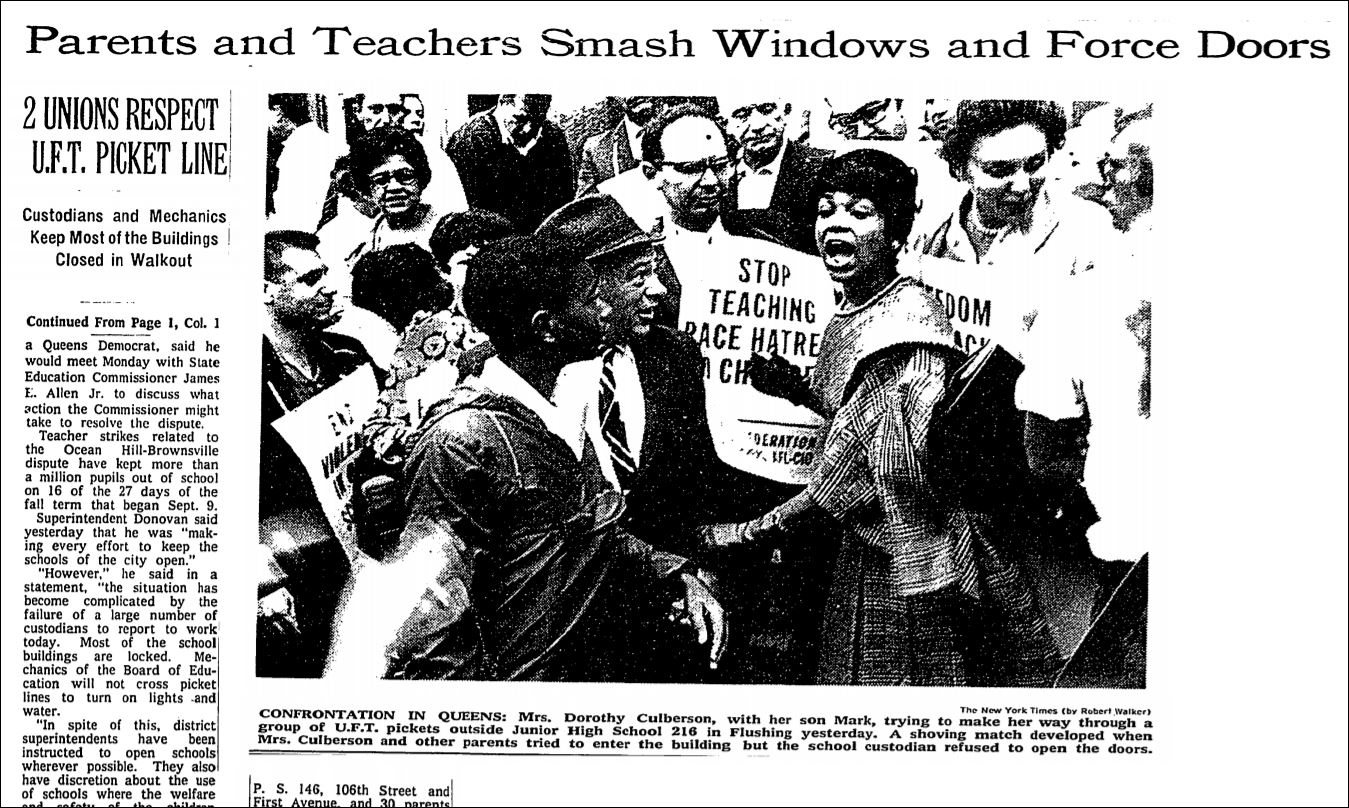

But the conflict intensified in 1968, first focusing on the abrupt reassignment of the 19 educators from Junior High School 271. Did community control give the community power to remove and reassign teachers, regardless of what the contract said or what the central office wanted? Opinions differed.

The strike finally ended in November, when the teachers were reinstated and the state disbanded the community control experiment. (A watered-down version was passed by the state legislature the following year.) The UFT had won. Community control — and the African-American and Puerto Rican community that had turned to it — lost. White UFT teachers returned to the school under police escort.

But the union victory came at a significant cost. The conflicts between unions and progressives had become so strong that, as Goldstein notes in her book, the teachers’ union “became downright villains… to large segments of the American left.”

Related coverage: Teacher strike coverage illustrates need to amplify parent, student voices

New York Times coverage 1968

A central complaint about the media coverage has been that it was biased along racial and gender lines. According to Brier, the New York Times and other mainstream print outlets did an inadequate job of reporting from the community perspective what the community wanted. The Ocean Hill-Brownsville community control effort “was not what they were focused on,” says Brier. “They were focused on the political process.”

Liberal outlets like The Nation, The Guardian, I.F. Stone’s Weekly, and the New York Review of Books were “willing to go beneath the headlines and sensationalism and go in the classrooms and evaluate what was going on,” according to Brier. But they, and the African-American paper the Amsterdam News, which had also thoroughly covered the events, had much smaller audiences.

Mainstream news also exaggerated reports of racist rhetoric from Ocean Hill-Brownsville against whites and Jews and failed to hold the UFT accountable for promoting them, according to Brier. The Times “bought the Shanker line that community control advocates were crazy anti-Semitic black nationalists.” In so doing, he says, journalists became complicit in the mischaracterization of the conflict and the demise of the local control experiment.

There is some agreement with some of Brier’s viewpoint.

The tabloids and broadcast news outlets told the simplest, most controversy-laden version of events, according to WNYC’s Jami Floyd, who reported the stations’ recent two-part remembrance of the events. The resulting coverage was “really ugly.” The New York Times emphasized what Floyd calls a “false polarity” between the community and the school system “that really didn’t exist.”

Ira Rifkin, a young reporter at the time of the strike, wrote that coverage of violent protests of that period often became “decidedly more in favor of the official police position” through the editing process by labeling community protestors as the instigators.

In her book, New York Times reporter Dana Goldstein notes that Shanker claimed that striking would protect white teachers against “black racists.” But, she asks, if the community control group were racist, why did they replace the removed and striking teachers with ones who were demographically similar – mostly white and Jewish?

But many of those who have studied and written about the events have come to different conclusions. The UFT likely had “a sympathetic audience” among reporters at then-liberal outlets like the Times and Daily News, UMass Boston history professor Vincent Cannato said, a “natural, almost subconscious bias” based on shared race and class. But the anti-Semitism was real and it “wasn’t created by the media. It was there.”

Lawrence University history professor Jerald Podair, who wrote a book about the events, notes that the Times was actually hostile to the strike. “Every newspaper in New York City except the Daily News was very critical of the UFT,” according to Podair, who cites a rally in October when Shanker complained bitterly about media coverage and his supporters started screaming at reporters who were covering the event. The UFT picketed the Times and used its perceived criticisms as a rallying cry. ”A hostile media was a good way of drumming up support for the union,” notes Podair. “You find an enemy and you can gain support.”

According to Shanker biographer Richard Kahlenberg, the coverage at the time inaccurately portrayed the union leader as anti-civil rights. “I think too much of the press coverage at the time saw the story … as a continuation of the civil rights struggle in the South,” writes Kahlenberg in an email. “That was a mistake. In fact, many New York City teachers – including their leader Al Shanker – were strong civil rights supporters. They viewed the fight not as black vs. white but as management vs. labor, something few reporters understood.”

However, journalists and historians such as these “are dead wrong” about what was really happening, Brier says. As evidence, Brier notes that AFT president David Selden blamed Shanker for having authorized the mass duplication and distribution of two offensive flyers – and then denying have any prior knowledge of the effort. He also cites journalist I.F. Stone, who wrote that the union was “exploiting natural Jewish fears of anti-Semitism in order to win the community’s support for the strike and for its major objective, which is to prevent effective decentralization and community control of the school system.”

“I hate to use the term ‘fake news,’ but that’s what it was,” says Charles Isaacs, who crossed picket lines to teach in the community and wrote a 2014 book about what happened. “And the media ran with it.”

Related coverage: Media Coverage Of Big-City Northern School Integration Efforts Was Deeply Flawed, Says New Book

Archival image of UFT teachers picketing in 1968

How would today’s media do, given such a tumultuous, racially charged conflict, complete with anxious parents and claims of flawed journalism and the possibility of disinformation? We don’t really know.

It’s been observed that some of the coverage of the 2018 teacher strikes over-emphasized the political narrative (the so-called “red state rebellion”), paid too little attention to the role of classified staff in supporting striking teachers, and gave too little voice to parents and students.

But this year’s strikes have had little of the racial and religious rancor of the events of 1968. And even the Chicago teachers strike a few years ago was relatively free of deep or prolonged expressions of animosity. It didn’t explicitly pit one part of the city against the other, and it wasn’t nearly as prolonged.

We’ll have to see what happens if and when such a conflict emerges again in education. It could be soon, if districts like New York City make meaningful attempts to address racial segregation and inequality. One thing’s for certain: it probably won’t be easy for journalists to get the story right.

Resources

WNYC: Ugly Teachers Strike Begins

The Nation: The Tough Lessons of the 1968 Teacher Strikes( Goldstein)

Jacobin: Ocean Hill-Brownsville, Fifty Years Later (Stivers)

SUNY Press: Inside Ocean Hill-Brownsville: A Teacher’s Education (Isaacs)

Citizen Ed: The Death and Life of Black Voice in the American Public School (Stewart)

Commentary: The 1968 New York City School Strike Revisited (Podair and Cannato)

Jacobin: The UFT’s Opposition to the Community Control Movement (Brier)

Yale University Press: The Strike That Changed New York (Podair)

Media & Values: Covering Conflict: How the News Media Handles Ethnic Controversy

Stanford: Register of the Fred M. Hechinger Papers

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alexander Russo

Alexander Russo is founder and editor of The Grade, an award-winning effort to help improve media coverage of education issues. He’s also a Spencer Education Journalism Fellowship winner and a book author. You can reach him at @alexanderrusso.

Visit their website at: https://the-grade.org/