How can teachers not only foster a growth mindset, but also create an environment in which this mindset can thrive?

We’re in a high school classroom in the basement of an old institutional-looking school building. There’s framed artwork on the walls rather than posters, and a large wooden desk in the corner — it feels like a college classroom. The students are preparing for a calculus exam, and the stakes are high. One student, Mary, looks up to the teacher and asks, “Did you say that x can be from 1 to infinity?” By asking this question, is Mary demonstrating a growth mindset? Does she believe that her intelligence or abilities can be changed through practice and learning?

Mary’s question could have several possible meanings. Perhaps, at the beginning of the semester, Mary’s teacher said, “Anyone who doesn’t ask a question each day will fail my class.” In that case, Mary’s question may have little to do with her mindset around learning; instead, she may have asked her question simply because she didn’t want to fail. Conversely, what if Mary never asked a question? Would this mean that she didn’t have a growth mindset? Not necessarily. She could very well believe that she can learn and grow through practice and hard work but is shy about speaking up in class. In short, having a growth mindset and displaying the behaviors associated with a growth mindset are not quite the same thing.

Although 77% of teachers have claimed that they are “familiar” or “very familiar” with the concept of growth mindset (i.e., the belief that it’s possible to change one’s intelligence or abilities), many teachers conflate growth mindset with other terms or concepts or have difficulties understanding how to best foster growth mindsets in their students (Beaubien et al., 2016). One concept that is associated with, but separate from, a growth mindset is intellectual risk-taking (IRT), which students demonstrate through behaviors such as contributing ideas, questions, or creative thoughts even when they might make a mistake or be judged by a peer or teacher (Beghetto, 2009; Soutter & Clark, 2021).

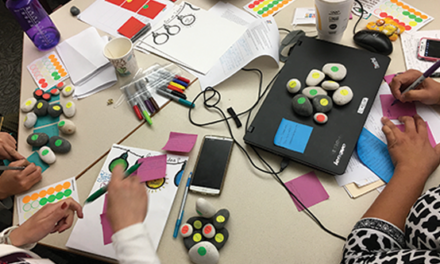

We spent a year observing 52 full-length classes and interviewing 23 students and teachers at a northeastern U.S. secondary school. All teachers at the school used a discussion-based pedagogy known as the Harkness method, which is centered on the egalitarian notion of students and teachers engaging in discussions to foster problem solving, collaboration, and deep comprehension (Williams, 2014). Growth mindset and IRT are consistent strengths of the school, and our research helped us discern the differences and overlaps between a growth mindset and IRT and understand what kinds of classroom environments foster both.

Mindset vs. behavior

A growth mindset represents a belief in the malleability of one’s intelligence and abilities. It stands in contrast to a fixed mindset, or a belief that one’s intelligence and/or abilities are predetermined at birth due to luck or other innate factors (Dweck, 2006, 2016; Farrington et al, 2012). Having a growth mindset is associated with a wide variety of positive academic outcomes, including curiosity (Dickhäuser et al., 2016; Jirout, Vitiello, & Zumbrunn, 2018; Ng, 2018; Ritchhart, 2015); resilience (Dweck, 2006); and academic achievement (Claro, Paunesku, & Dweck, 2016; Haimovitz, Wormington, & Corpus, 2016; Sisk et al., 2018; West et al., 2016). Growth mindset research has often focused on the positive impact of brief psychological interventions, such as teaching students that their brains can grow larger, to help students shift from fixed to growth mindsets (e.g., Sarrasin et al., 2018; Yeager et al., 2019). However, a body of literature also points to the importance of creating an environment where growth mindsets can thrive (Bardach et al., 2020; Yeager et al., 2019). For example, mastery-oriented classroom climates — those focused on learning over performance — tend to be more associated with students who have growth mindsets (Bardach et al., 2020).

Intellectual risk-taking refers to actions and behaviors, whereas a growth mindset refers to beliefs about oneself.

Intellectual risk-taking involves engaging in certain learning behaviors regardless of potential errors or judgment (Beghetto, 2009; Soutter & Clark, 2021). While these risk-taking behaviors are often associated with having a growth mindset, intellectual risk-taking refers to actions and behaviors, whereas a growth mindset refers to beliefs about oneself. IRT behaviors might include sharing ideas, asking questions, speaking up in class, exploring viewpoints contrary to one’s own, or attempting to learn something new (Beghetto, 2009; House, 2002). Like growth mindset, taking intellectual risks at school is linked to beneficial academic results for students, including higher levels of academic achievement (Beghetto, 2009; Streitmatter, 1997); positive studying behaviors (Cetin et al., 2014); engagement, motivation, and enjoyment of learning; problem-solving skills; and perseverance through difficulties (Cetin et al, 2014).

Growth mindset and IRT often are found in tandem, which suggests that helping students to grow in their beliefs about learning can help influence their learning behaviors. But how do we foster these beliefs and actions? Do we have to start by fostering a growth mindset, or could we begin by trying to cultivate students’ risk-taking behaviors in hopes that this, in turn, bolsters their belief in learning?

Carol Dweck (2006) has noted that a growth mindset is inherently linked to one’s ideas about risk-taking and failure, noting that “people’s ideas about risk and effort grow out of their most basic mindset” (p. 9-10). However, fostering a growth mindset with students does not guarantee that those students will display intellectual risk-taking behaviors. For this reason, we aim to disentangle the two constructs so that we can implement pedagogical practices targeted to each.

Promising practices

Fostering a growth mindset by normalizing confusion

The literature on growth mindset emphasizes the importance of valuing the learning process rather than focusing on the final product (Dweck, 2016). In nearly every class we visited during our research project, we saw students working together not necessarily to come to a single conclusion, but to welcome multiple perspectives. As one student explained:

You concentrate on understanding the thought process where most of the work is happening, not the solving. It’s where you’re getting from point A to point B, not point A to Z. You really get to learn about how to think.

However, building this kind of culture can be difficult. How did the teachers authentically create this kind of environment? One thing that we repeatedly saw and heard was that teachers did not try to avoid confusion and disagreements, but actively embraced them. One teacher shared:

I teach them that it is their confusion that is in a way the engine driving the learning. [I tell them to] be sensitive to those moments where you’re going, “Wait I don’t get this” and mark that . . . And if you can bring that [confusion] to us in class, you’re gonna help us all get this. So, I privilege confusion. I privilege questions.

This sentiment of “privileging confusion” reflects a completely different way of conceptualizing school and learning from what most students are used to. Rather than seeking to hastily move past problems to come to a solution, to squash disagreements in order to arrive at a compromise, or to create shame around confusion, teachers encouraged students to fully embrace and work through these crucial elements of learning.

Similarly, teachers gave students multiple opportunities to solve problems on their own so they could practice problem-solving and collaboration skills. One student explained what this looks like in a math classroom:

You’re given problems you haven’t really learned how to solve yet. You solve them on your own, and then if you didn’t understand a problem, you could still write it on the board. You can go up in front of the class and say, “I kind of understood it, but I also didn’t understand fully how to solve it. I got to this point, and I didn’t know where to go next.” And the class will help you and that’s normal.

In the classrooms we observed, not knowing the answer, confusion, and even failure were treated as normal and even worthy of celebration. This aligns with the research on how a growth mindset develops (e.g., Dweck, 2016).

Foster intellectual risk-taking through explicit instruction

In our research, we identified pedagogical moves that fostered intellectual risk-taking behaviors associated with a growth mindset. For example, teachers coached their students explicitly on how to engage in productive dialogue using the Harkness method employed at the school. One teacher explained:

I give them very explicit training in how to frame a question. I have them write discussion questions and then I give them written feedback and we talk about them: “Why is that less fruitful and less open than that? How can we change that? Let’s open that up a little bit.”

Similarly, another teacher shared how she coaches students who may be struggling to enter classroom discussions:

Question-asking is the safest way to enter a conversation; it’s the lowest risk. The kids who are quiet, often I tell them two things. I say, “Come in with the first question. You don’t have to worry about synthesizing your idea to somebody else’s.” And the other piece is I say, “Think of me like a linebacker, and I’m gonna block for you, and then you come in right after.” Because oftentimes right after the teacher speaks — because we don’t speak that much — there’s a little couple of beats while kids are thinking about it. . . . So those are the two places where I recommend kids who are struggling with Harkness to participate until it becomes intuitive and natural.

Teachers also described how they set students up for success by allowing them to observe a discussion and to discuss what they notice so that they can have a foundation to build on when joining discussions themselves:

At the very beginning of the year, we bring in the entire 9th-grade class to a Harkness demonstration. . . . We ask our 9th graders to watch, to observe. What do you see? What surprised you? So that’s how we begin, that’s in a way our text. And it’s, you know, “Oh my gosh, they didn’t raise their hands!” “Oh my gosh, two people spoke at once; one said: Oh no, you go ahead!” “I really like the way they used each other’s names.” “I really liked the way they disagreed when they said I see where you’re coming from . . . however I also think this, so what do you think of that?” So, we’re giving them, very explicitly, a model.

Teachers did not expect 9th graders to enter high school already knowing how to have a meaningful discussion where risks are encouraged and opposing viewpoints embraced. They approached the construction of this kind of environment in a systematic, step-by-step way to establish classroom routines and expectations and helped students build the skills they would need (see also Ritchhart & Church, 2021).

Fostering growth mindset and intellectual risk-taking by creating a safe classroom environment

Our research found that one of the ways teachers can support the development of both a growth mindset and intellectual risk-taking is to thoughtfully and intentionally create a safe classroom community where students have opportunities to support one another and where students and teachers alike genuinely value mistakes. This is, of course, much easier said than done. The teachers approached this critical and complex task by employing specific strategies to build a sense of camaraderie and trust among students. One teacher shared:

For me, the fundamental ingredient is interpersonal chemistry and trust, so a lot of what I do is oriented toward developing that from the first day. I begin every class with some sort of activity that requires them to physically stand up, change seats, and engage with somebody in the class. I do a lot of very brief exercises that have nothing to do with text but everything to do with eye contact and conversation and expression of self because these are for me the nonnegotiables. . . . If you can get kids trusting each other, if you can get kids enjoying the space with each other, it’s gonna manifest in far deeper, far better intellectual conversations later. So for me that’s the core of everything that I do: comfort with self, trust, and enjoyment of each other.

Students told us that this kind of environment allowed them to risk being vulnerable, which in turn allowed for more meaningful discussions in which they experienced growth. For example, one student shared:

My history teacher this term has said a lot of our best discussions come from being vulnerable: Say something if you think it, even if it’s not something most people will agree with, because that’s what creates the best discussions.

Finally, students also spoke about the power of a classroom driven by student learning and questioning. Teachers we spoke to stayed out of classroom discussions as much as possible so that students could build on one another’s points, and students told us that this made them more willing to speak up and take risks:

When I’m being posed a question from a peer versus when I’m being posed a question from a teacher, I kind of have a different approach, or I react differently. When you’re in the very conventional teacher-student dynamic, it’s a lot more formal, and you have to get the right answer; otherwise, the teacher will judge you. . . . But when you’re posed a question from your peer or challenged by a peer, I find myself more free and willing to dig deeper and maybe make some mistakes. There’s no conditions on the thoughts you put out.

Targeting instruction to what students need

Perhaps you are a teacher who already engages in many of these practices with your students — you create a trusting, safe classroom where students feel like they belong, you value mistake-making and confusion, and you deliberately teach your students strategies for taking risks. Is there still value, then, in knowing when a student is displaying a growth mindset versus when they are only taking intellectual risks? We would argue yes, because this knowledge allows teachers to better target appropriate follow-up practices or interventions to specific students.

We hope all students can understand that learning is just right around the corner when we all take risks and explore together.

Perhaps you have a student who rarely takes part in class despite the use of best practices. What could you do? First, you could investigate whether the student feels like they will learn anything by engaging in class. You might ask the student questions about their thoughts on learning in general, or about your particular subject or topic, and discover that the student doesn’t understand that the mind can grow and change or has always been told their intelligence was innate. For students like this, who don’t have a growth mindset, a first course of action would be showing them that confusion is a normal part of learning and not a sign that they can’t ever understand the topic.

On the other hand, you might find out that your student does have a growth mindset but remains reluctant to participate in class. What then? You could question why the student does not feel confident in taking risks: Is it because they do not feel that they have the skills needed to engage? Do they need more help in forming questions, or do they feel the need to better understand the subject? Or perhaps they are quieter than their classmates and need their teacher to serve as “linebacker” by creating space for them in the conversation.

Ultimately, we hope all students can understand that learning is just right around the corner when we all take risks and explore together, just as this student did when posing a question about cell specialization: “I don’t think we ended up answering the question because it’s kind of not an answerable question — yet. But it felt cool to ask and find that other people were curious about it, too.”

References

Bardach, L., Oczlon, S., Pietschnig, J., Lüftenegger, M. (2020). Has achievement goal theory been right? A meta-analysis of the relation between goal structures and personal achievement goals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112 (6), 1197-1220.

Beaubien, J., Stahl, L., Herter, R., Paunesku, D. (2016). Promoting learning mindsets in schools: Lessons from educators’ engagement with the PERTS Mindset Kit. PERTS: The Project for Education Research That Scales.

Beghetto, R.A. (2009). Correlates of intellectual risk taking in elementary school science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 46 (2), 210-223.

Cetin, B., Ilhan, M., & Yilmaz, F. (2014). An investigation of the relationship between the fear of receiving negative criticism and of taking academic risk through canonical correlation analysis. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 14 (1), 146-158.

Claro, S., Paunesku, D., & Dweck, C.S. (2016). Growth mindset tempers the effects of poverty on academic achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113 (31), 8664-8668.

Dickhäuser, O., Dinger, F.C., Janke, S., Spinath, B., & Steinmayr, R. (2016). A prospective correlational analysis of achievement goals as mediating constructs linking distal motivational dispositions to intrinsic motivation and academic achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 50, 30-41.

Dweck, C.S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Dweck, C.S. (2016). The remarkable reach of growth mindsets. Scientific American Mind, 27 (1), 38-41.

Farrington, C.A., Roderick, M., Allensworth, E., Nagaoka, J., Keyes, T.S., Johnson, D.W., & Beechum, N.O. (2012). Teaching adolescents to become learners. The role of noncognitive factors in shaping school performance: A critical literature review. University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research.

Haimovitz, K., Wormington, S.V., & Corpus, J.H. (2011). Dangerous mindsets: How beliefs about intelligence predict motivational change. Learning and Individual Differences, 21 (6), 747-752.

House, D.J. (2002). An investigation of the effects of gender and academic self-efficacy on academic risk-taking for adolescent students [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Oklahoma State University.

Jirout, J.J., Vitiello, V.E., & Zumbrunn, S.K. (2018). Curiosity in schools. In G. Gordon (Ed.), Psychology of emotions, motivations and actions. The new science of curiosity (pp. 243-265). Nova Science Publishers.

Ng, B. (2018). The neuroscience of growth mindset and intrinsic motivation. Brain Sciences, 8 (2), 20.

Ritchhart, R. (2015). Creating cultures of thinking: The 8 forces we must master to truly transform our schools. Jossey-Bass.

Ritchhart, R. & Church, M. (2021). The power of making thinking visible: Practices to engage and empower all learners. Jossey-Bass.

Sarrasin, J.B., Nenciovici, L., Foisy, L.M.B., Allaire-Duquette, G., Riopel, M., & Masson, S. (2018). Effects of teaching the concept of neuroplasticity to induce a growth mindset on motivation, achievement, and brain activity: A meta-analysis. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 12, 22-31.

Sisk, V.F., Burgoyne, A.P., Sun, J., Butler, J.L., & Macnamara, B.N. (2018). To what extent and under which circumstances are growth mind-sets important to academic achievement? Two meta-analyses. Psychological Science, 29 (4), 549-571.

Soutter, M. & Clark, S. (2021). Building a culture of intellectual risk-taking: Isolating the pedagogical elements of the Harkness method. Journal of Education, 1-12.

Streitmatter, J. (1997). An exploratory study of risk-taking and attitudes in a girls-only middle school math class. The Elementary School Journal, 98, 15-26.

Yeager, D.S., Hanselman, P., Walton, G.M., Murray, J.S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., . . . & Dweck, C.S. (2019). A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature Research, 573, 364-369.

West, M.R., Kraft, M.A., Finn, A.S., Martin, R.E., Duckworth, A.L., Gabrieli, C.F., & Gabrieli, J.D. (2016). Promise and paradox: Measuring students’ non-cognitive skills and the impact of schooling. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 38 (1), 148-170.

Williams, G. (2014). Harkness learning: Principles of a radical American pedagogy. Journal of Pedagogic Development, 4(3), 58-67.

This article appears in the September 2022 issue of Kappan, Vol. 104, No. 1, pp. 50-55.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Madora Soutter

Madora Soutter is an assistant professor in the Department of Education and Counseling at Villanova University, Villanova, PA.

Shelby Clark

Shelby Clark is senior research manager of Project Zero at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA.