The best mentoring meetings focus on the underlying reasons for teachers’ instructional decisions.

Because effective teaching begins with careful planning for instruction, novice teachers (both student teachers and beginning teachers) can benefit greatly from mentoring in this area. Yet, much of the work of teacher planning can’t be observed directly, since it involves the hidden, internal process of envisioning how one’s plans might unfold in the classroom (Kennedy, 2006). To help novice teachers learn to plan effectively, then, mentors must find a way to make this process visible.

Co-planning — in which a mentor and novice meet to discuss options for teaching upcoming classes and decide together how best to proceed — can be a fertile means of teacher development (Feiman-Nemser & Beasley, 1997). However, mentors often neglect to take advantage of the opportunity to talk with novices, explicitly, about the hidden work of envisioning how instruction will go and using that process to inform one’s decisions about what to teach, how to teach it, and why (Feiman-Nemser & Beasley, 1997; Schwille, 2008).

How does efficient co-planning limit novice learning?

Recently, in my work with a study group for veteran teachers in an urban public school, I observed participants pursue two very different approaches to mentoring (Stanulis et al., 2018). Darcy, a 6th-grade teacher and mentor to a student teacher named Amanda, described co-planning as an opportunity to model her teaching practice: “I think I model a lot of things that [Amanda] could use [in] actual lessons or [with] discipline, or ways to plan a week so that it’s not the same.” In contrast, Brian, a 5th-grade teacher, described co-planning as an opportunity to help novice teachers think about their own learning goals, pushing them to identify what they need to learn about instruction. “We’re not just coming up with lessons for next week,” Brian told me. “We’re also [asking], ‘Hey, how are we moving you forward, how are we getting you into more of a leadership role?’”

In my experience working with mentors in U.S. elementary schools, I’ve found Darcy’s approach (which aims to show novice teachers what to do) to be much more common than Brian’s (which aims not just to show novice teachers what to do but also to get them thinking and talking about their goals for professional learning).

When I observe mentor teachers, I tend to find that they use their co-planning sessions mainly to focus on scheduling. For example, the bulk of Darcy’s time with Amanda was devoted to “filling in the boxes” on the schedule for the upcoming week’s classes. Darcy frequently talked with Amanda about what to teach and when, but she very rarely engaged her in conversations about how to teach and why. See, for example, what happened when Amanda and Darcy were planning reading lessons for the week:

AMANDA: What do we want to do Friday? I have no idea.

DARCY: Well, I still have some of the myths they can read independently. I will grab for you . . . I have to go look in the file. [Talking to self while writing on the schedule: Some of the myths for Friday reading.] Because that would be an easy one. I’m going to write down Black artist, just in case I come across somebody between now and the end of the day that I could pull for you. What else are you . . . let’s see . . .

AMANDA: OK.

DARCY: Your reading. I don’t know.

AMANDA: That’s what we don’t know. That’s what I need, too. What should I do for tomorrow for reading?

DARCY: I can’t remember if there’s anything else within [the curriculum] after [the last story]. There was another one there, or I have some plays of historical Black characters. They’re more of a play so they could read it in smaller groups. That would be a good one, too. Those are already copied, I just have to dig them out.

Darcy and Amanda’s planning consisted of finding activities that fit the curriculum. While Darcy provided Amanda with ideas and resources, she did not talk to her about objectives (e.g., What do students need to learn from reading myths? Why are we looking for Black artists and characters?); how to group or differentiate based on student need, and how the lesson might go (What might confuse students? What are the best ways to determine who reads what roles in the play?). Darcy herself acknowledged this: “I didn’t do a very good job of zeroing in on one lesson and just making that [lesson] the conversation . . . But, we’d usually kind of look through the week, pick some specific lessons, and work on what to anticipate, what things to change, what [materials] to prepare.”

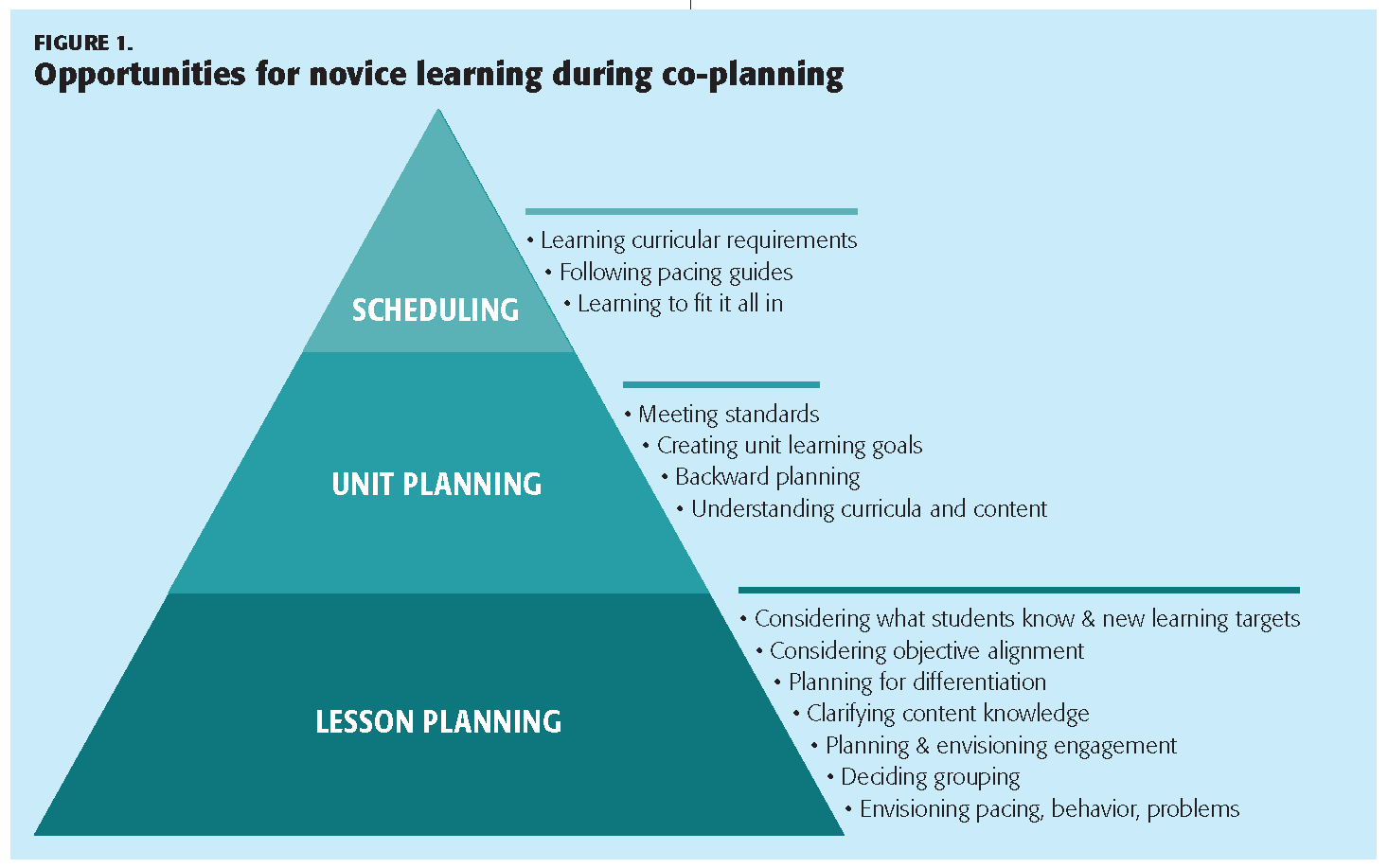

Of course, scheduling is just the tip of the iceberg of what novice teachers need to learn (see Figure 1) in order to become independent decision makers who take into consideration what students need to learn, what supports they need, and what might happen during a lesson.

The incentive to zero in on scheduling is powerful, though, given the time crunch mentor teachers tend to face every day — with a single co-planning session of this sort, they can sketch out a week’s worth of lessons. Further, since veteran teachers have likely thought through the how and why questions already, earlier in their career, they may no longer see the need to think about those questions when planning their lessons. Unless they are using a new curriculum or revising an old one, they can just pencil in some tried and true lessons and units. This sort of planning may strike them as both efficient and, given their professional experience, sufficient. What they may not realize, though, is that it denies novice teachers an important opportunity to learn.

How can co-planning become a learning opportunity?

Mentor teachers can shift their role in co-planning sessions by thinking about a wider and deeper range of novice learning goals. Instead of providing copies of lesson plans and explaining how they usually teach the class, educative mentors think aloud about why they make specific choices (taking into consideration the curriculum, standards, students’ needs, and so on).

Educative mentors like Brian start from a very different perspective on planning than schedule-focused mentors like Darcy. During co-planning sessions, Brian makes sure his mentees are learning how to consider a) what the students need to learn, b) the specific needs of students based on prior assessment, c) the best ways to engage and challenge students to meet learning goals, and d) how students might respond.

Mentors can guide novices through this thinking by focusing on a unit, but lesson planning (because it includes less content) allows more time for in-depth conversation about the why questions. However, as Darcy’s example demonstrates, just planning a lesson together is not automatically educative. Mentors need to think carefully about the most effective way to engage novice teachers in co-planning sessions.

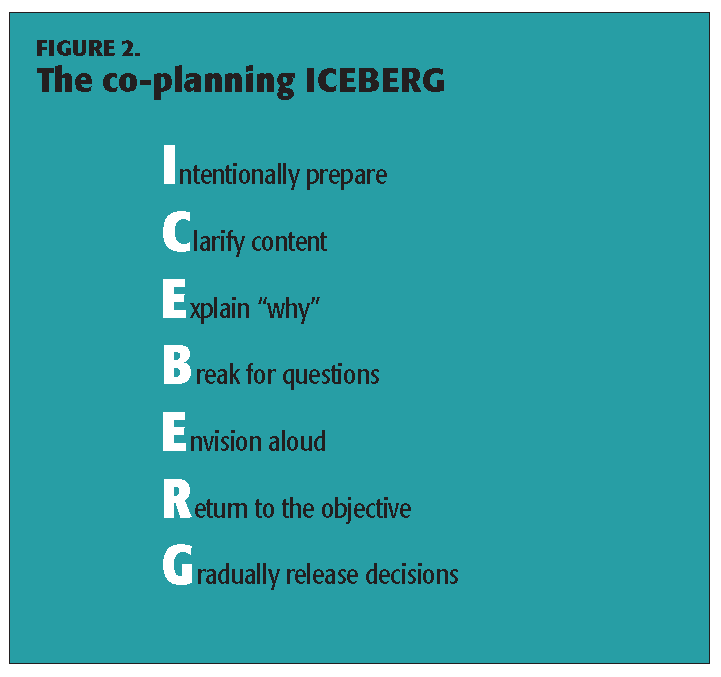

Neither Darcy nor Brian had time for co-planning during the school day, so the time they spent co-planning needed to be as efficient as possible. One way for mentors to make the most of co-planning time together is to prepare for their sessions ahead of time. Mentors need to know going in what they are going to teach the intern and why. The acronym ICEBERG (see Figure 2) can help mentors plan what they will discuss during co-planning sessions.

Intentionally prepare

An educative mentor considers ahead of time the novice’s professional learning goals and weaves those goals into the co-planning sessions. For example, when reflecting on one of his co-planning sessions with Molly, Brian said,

My main focus was to help [Molly] to think about differentiation as well as continuing to engage the students in higher-order thinking skills . . . I was challenging [Molly] to really dig into the content and help to understand the importance of differentiation.

During a co-planning session for a single science lesson on ecosystems, Brian and Molly not only planned for the lesson but also spent time on strategies for differentiation and higher-order thinking.

Clarify content

Often, novice teachers struggle with concepts and content they are teaching for the first time. Educative mentors can use co-planning sessions to explain content and clarify misconceptions both novices and students may have. See, for example, how Brian guided Molly during their co-planning for a lesson on ecosystems:

BRIAN: Do we want them to use the definitions for predator/prey, all those things you had in there?

MOLLY: Like the tertiary consumer? . . . That would be hard if you get way far into it.

BRIAN: Yeah, but at least some producers that are in that area.

MOLLY: Yeah, I think they should—

BRIAN: In the food web, they’re all consumers except for the base level.

MOLLY: I think it might be interesting to sort out who is only a prey and who is a predator and prey and who is only a predator, classify those.

Brian made sure to clarify the concept of the food web with his student teacher, specifically that all except the base level of the web were consumers, while simultaneously helping her envision where students might be confused on how to label predator and prey.

Explain the “why”

Depending on who is leading the co-planning session and doing the teaching, the novice or mentor should explain aloud why they are making certain instructional decisions about what or how to teach (Pylman, 2016). In the following example, Brian is co-planning a vocabulary lesson with Molly and trying to figure out how to help kids understand the activity:

Maybe we can even model that or . . . like if we see kids talking about it, maybe we could say, “Hey, would you mind writing that down and then doing it in front of the class so they can see you talking about it?” Because I think that they like to perform in that regard. If we can get them to be the ones that — “You can totally teach everybody this because that was so awesome what you did there,” and really build them up. Then give them that power to be in front of the kids, maybe they’ll pay a little more attention when kids are up there instead of us.

Brian is not only brainstorming ideas for how to better teach the vocabulary activity, but he is explaining why he thinks it would be a good idea for students to model for each other.

Break for questions

If the mentor is leading the co-planning session and going to teach the lesson, the novice should stop the mentor and ask questions that get the mentor to explain why. For example, Why do you do it that way? Why do you use that book? If the novice is leading the co-planning session and teaching the lesson, then the mentor should ask probing questions to encourage the novice to explain their decisions (Why do you want the students to write three paragraphs? What are the comprehension skills that we’re working with here?); to envision what might happen (What are some possible problems that you could see with that?), and think through organizational or management concerns (How are you going to group the students? When and where will they turn in their work? Are you going to grade it? How? Just by effort? By a rubric?).

Envision aloud

A staple of teacher planning is envisioning what might happen in a lesson. An educative mentor voices this process out loud. For example, Brian envisions aloud with Molly how to ensure students have enough work to do:

Some of the kids . . . they finish superfast because they get it and they know what they’re doing. Maybe at those points, we can just start saying, “Why don’t you make a T-chart and put synonyms on one side and antonyms on the other?”

If the novice is leading the co-planning session and plans to teach, the mentor encourages the novice to envision aloud. For example, Molly envisions a problem students might have with an upcoming major project:

I feel like if we tell them the whole project, I can imagine a few of them right now already freaking out. So maybe just give them the next step as they’re ready.

Return to the objective

Backward planning, or thinking about the end goals the students will need to meet at the start of the process, is a common planning strategy (Wiggins & McTighe, 2001). In educative co-planning sessions, mentors or novices backward plan by stating the objective(s) of the lesson — What do we want students to know and/or be able to do at the end of this lesson/unit? Then, the mentor and novice keep returning to those objectives when making decisions about activities and assessments. Does this align with (or measure) what we want students to know and be able to do? For example, when co-planning the culminating activity on ecosystems, Brian points back to the objectives:

We’re looking to see that they understand the purpose of food webs, or food chains, or the passing of energy from living organisms within an ecosystem. The important information that we would need to have in there is . . .

Gradually release decision making

There comes a time in most mentoring relationships when the novice teacher needs to take on more responsibility and become independent. The mentor needs to prepare for this step by gradually releasing responsibility to the novice. For example, instead of telling the novice what to do, the mentor may simply make suggestions while letting the novice choose — thus sharing the decision making. Some mentors describe this process as “letting the intern experiment” in their classrooms. For example, in a mentor study group session, Brian said it was important to ask novice teachers, “What do you think, or what might you try, or how might you start? And just kind of give them that opportunity to take a risk.” When co-planning, both Brian and Darcy often deferred to their student teachers to make decisions by asking them for ideas and telling them it’s OK to use a different method.

Planning to learn

Besides preparing for a lesson, educative co-planning considers the novice teacher’s learning and how to prepare that novice to plan thoughtfully and teach independently. Teachers spend a lot of time envisioning in their heads how they will enact their teaching, and it is vital that mentors learn to think and envision aloud so novices are able to learn from them. Bringing planning and learning together makes co-planning sessions a worthy use of the mentor and their novice’s time.

References

Feiman-Nemser, S. & Beasley, K. (1997). Mentoring as assisted performance: A case of co-planning. In V. Richardson (Ed.), Constructivist teacher education: Building a world of new understandings (pp. 107-125). London: Routledge.

Kennedy, M.M. (2006). Knowledge and vision in teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 57 (3), 205-211.

Pylman, S. (2016). Reflecting on talk: A mentor teacher’s gradual release in co-planning. The New Educator, 12 (1), 48-66.

Schwille, S.A. (2008). The professional practice of mentoring. American Journal of Education, 115 (1), 139-167.

Stanulis, R.N., Wexler, L., Pylman, S., Guenther, A., Farver, S., Croel-Perrien, A., . . . Ward, A. (2018). Mentoring as more than “figuring it out” on your own: Practices in educative mentoring. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2001). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Citation: Pylman, S. (2018). In co-planning, scheduling is just the tip of the iceberg. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (4), 44-48.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Stacey Pylman

STACEY PYLMAN is an assistant professor in the Office of Medical Education Research and Development, College of Human Medicine, at Michigan State University in East Lansing. Previously, she was an internship coordinator, instructor, and doctoral student in the College of Education.