| Above: West End’s school daze: How students, parents, and staff are grappling with a new learning reality. (2020).

The success of the West End issue led us to a third neighborhood-focused issue in the city of Forest Park yet again with a strong focus on schools.

We scoured local publications including the Clayton Crescent, along with traditional coverage, and discovered an ethnically diverse city with a significant Hispanic and Vietnamese population located in the shadow of the airport, faced a formidable set of barriers exacerbated by the pandemic: poverty, over-policing, housing insecurity, and a public school system that’s still regaining its footing 13 years after losing its accreditation.

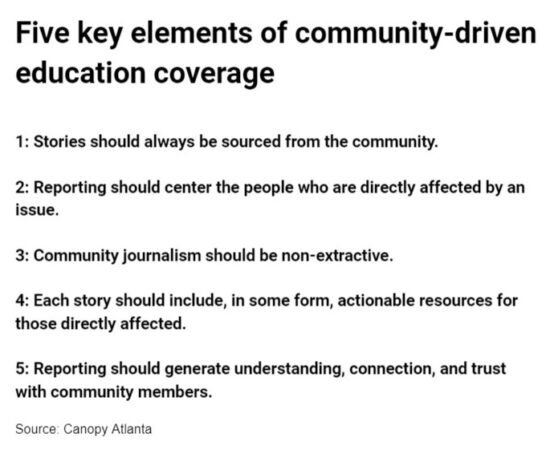

We knew any education coverage in Forest Park would have to contend with these intersectional forces. And we know that our efforts would only succeed if we followed the practices we’d adopted covering the West End:

1: Stories should always be sourced from the community.

Despite the story that demographics told, when we visited Starr Park, the family-friendly public space located a block off Forest Park’s main corridor, community residents spoke proudly of their neighborhood when asked three open-ended questions about the community’s top news priorities. For example, “What do you love about Forest Park,” or “What resources or information might help you?”

Ultimately, 120 people shared their thoughts through a questionnaire form, phone interviews and in-person conversations, an overwhelming response doubling the respondent reach of the previous community engagement effort in West End. As expected, schools were a priority, and it was clear that an educational story would make a significant contribution to the issue.

A paid four-member community editorial board further refined their neighbors’ feedback on schools. Local school council chair and parent Kesha Crockett steered the conversation about education during the weekly editorial board meetings. After the board’s deliberations, it appeared that our educational journalism coverage would have plenty of moving parts.

2: Reporting should center the people who are directly affected by an issue.

After reviewing the pared down list of education topics, the community issue editors recommended a series of five “annotated” as-told-to’s that would address multiple educational topics dependent on those interviewed.

The editors also assigned a tenacious interviewer in local journalist Jewel Wicker to tell the story. We paid four residents with ties to Forest Park to learn the tenets of community journalism. Three of these community journalism fellows with strong interests in education journalism partnered with Wicker for the story. These fellows contributed research and played a crucial role in sourcing interviewees.

In total, eight subjects told their perspectives in the final story, published September 2021.Through the vantage point of students, parents, a principal, and the local school council, the story examined what success looked like for the Forest Park school system while addressing lingering barriers of increased housing insecurity for students, teacher retention issues, and mental health access for youth.

3: Community journalism should be non-extractive.

Canopy Atlanta’s community journalism methodology is a quiver of guidelines aimed at achieving non-extractive journalism. Non-extractive journalism is not achieved by happenstance but by intentional planning.

We’ve found that much of traditional or legacy journalism tends to exist separate from the communities covered. Extractive and deficit-centered coverage has eroded community trust in journalism, especially in working-class, Black, and immigrant communities across the metro.

We discovered that local governments and agencies don’t always disseminate or present information in ways in which residents can engage, including barriers to attend public meetings or access information on public websites. We believe the disconnection of journalism from its communities has exacerbated inequality, creating a situation in which residents cannot always equitably access or shape the information — public records, civic knowledge, community narratives — they need to thrive.

It’s very important to us that we don’t just drop in, listen, report, and then leave. By committing to only three neighborhood-centered issues a year, we intentionally stagger our community interactions of listening/training/sharing over several months.

We value resident journalists by paying equitable compensation for their time. Community editorial board members and community fellows also receive a stipend for their work.

Everyone must commit to non-extractive journalism guidelines. All contributing journalists are expected to present their stories back to the community and be held accountable for their reporting.

Following the release of the issue, we live-stream panel discussions with editors and writers providing an opportunity for the public to provide story feedback.

Over two Community Issues, Canopy has produced dozens of narrative, investigative, and multimedia stories; trained 10 Journalism Fellows to build their communities’ abilities to keep accessing information and telling stories; and enabled hundreds of metro Atlantans to participate actively in the production of journalism about their communities.

4: Each story should include, in some form, actionable resources for those directly affected.

Telling stories is important, but it’s not enough.

In addition to stories, we compile resources on the topics that residents told us they wanted, including educational, mental health assistance, and policing and immigrant resources. We also provide convenient links to government and city services.

Our community journalism fellows and community liaisons compiled information that built out the Forest Park Resource Guide and Asset Map.

In our reporting, we encourage the use of open records to incorporate relevant and previously unreported civic information. In the Forest Park issue, we obtained the school budget through an open records request and incorporated it into our reporting and resource guide.

We also translated multiple stories from the Forest Park issue to make sure our Spanish- and Vietnamese- speaking community members can access the journalism they said they needed.

5: Reporting should generate understanding, connection, and trust with community members.

Fleshing out a community concern journalistically takes time and trust which allows for continuity and deep reporting. One concern not covered in our education story was students facing housing insecurity.

This October, we returned to Starr Park for a community launch of the digital issue that included a panel discussion about Forest Park schools with resident panelists Kesha Crockett (Community Editorial Board Member) and Rachel McBride (Forest Park Fellow).

During the panel discussion, McBride, who helped source student interviewees during Wicker’s reporting, announced that she was continuing our educational journalism coverage with an ethnography about Forest Park’s high student mobility rates.

“Canopy Atlanta helped me streamline what stories I want to tell, and what I care about relaying elsewhere,” said McBride. “Those stories are of home, the people are home … Build things that are beautiful and tell those stories from home.”

We will shepherd, edit and publish McBride’s stories as additional reporting for this community issue.

Brent Brewer is a Canopy Atlanta community journalism fellow and recent board member. He has been the managing editor/publisher of the Our West End Newsletter, a hyperlocal bi-monthly print publication, since 2006. You can follow Canopy Atlanta on Twitter at @canopyatl.

Related stories and columns from The Grade

Better ways to cover Black homeschooling

How book controversy coverage is missing the mark

A white parent’s perspective on media coverage of Black schools

How do we get Black kids’ literacy to matter?

Putting parents front and center |