The shift from the No Child Left Behind Act to the recently authorized Every Student Succeeds Act could beckon a renaissance of K-12 arts education in the U.S.

When Congress passed the Every Student Succeeds Act in 2015, arts advocates were relieved to see that the new law placed the arts alongside reading and math as integral parts of a “well-rounded education.” However, while this sent a welcome message to advocates, the status quo really didn’t change: The arts also had been described as a “core subject” in the No Child Left Behind Act (Zubrzycki, 2015). Of much greater consequence to arts educators are two other aspects of the new law.

Because ESSA reins in the federal government’s influence over local decisions about academic standards and accountability, states and districts will have more power to decide how best to gauge student progress toward becoming well-rounded. This promises to be a net positive for arts advocates since it removes a burden created by the previous law. By the government’s own estimation, NCLB’s narrow focus on achievement in reading and math led to decreased time spent on arts education, particularly in schools identified as “needing improvement” (GAO, 2009). Now that the threat of sanctions based on test scores has been reduced, local education authorities should feel less pressure to reduce arts instruction in favor of other subjects.

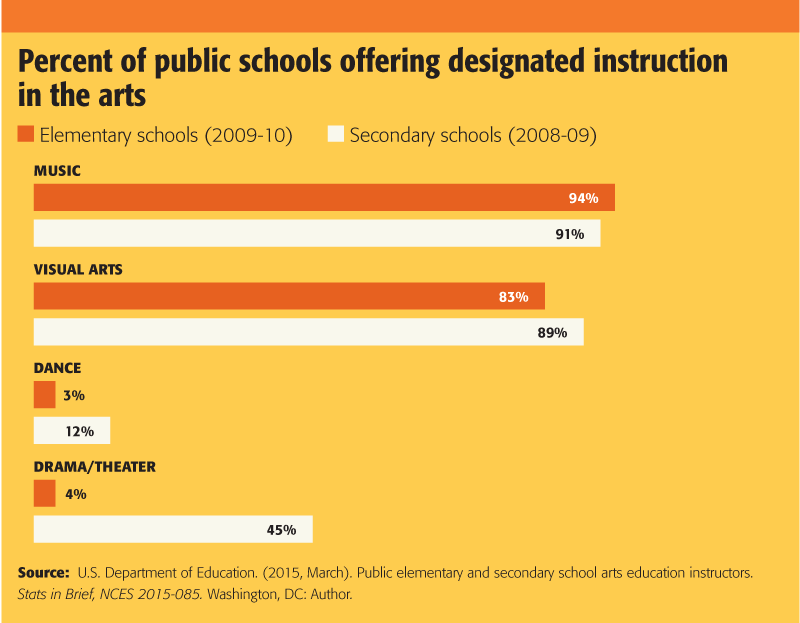

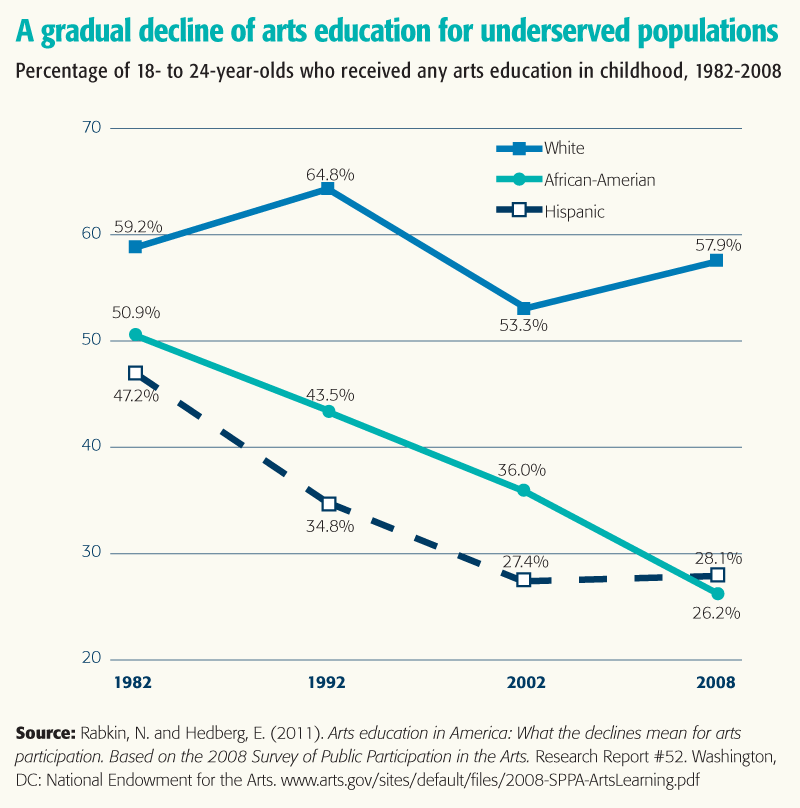

Even as they enjoy greater autonomy, however, many schools and districts will continue to struggle against resource constraints. Over the past quarter of a century — and since well before NCLB was enacted — access to arts education in the public schools has become less and less equitable, with minority students and students attending high-needs schools most often shortchanged (Rabkin & Hedberg, 2011; Yee, 2014; GAO, 2009; Stringer, 2014). This “arts opportunity gap” has grown so wide, noted former Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, as to become a “civil rights issue” (Walker, 2012).

This brings us to the second opportunity that ESSA provides: In an effort to close that opportunity gap, Congress has extended support for the Assistance for Arts Education program, which is designed specifically to benefit disadvantaged students. Among other things, it will offer grants for “outreach activities that strengthen or expand partnerships among schools, local education agencies, communities, and centers for the arts,” as well as encouraging coordination among “public or private cultural agencies, institutions, and organizations, including museums, arts education associations, libraries, and theaters” (ESSA, Section 4642).

As we argue below, this assistance, together with the shift toward greater local autonomy in educational decision making, has real potential to usher in a new era of cooperation among public schools and community-based arts organizations.

Arts-based partnerships

The formation of arts-based school-community partnerships has become a popular strategy for addressing declines in arts resources and opportunities for K-12 students. The most successful programs tend to take the form of a coalition that links cultural organizations and artists to local schools with oversight provided by a board that includes school and district officials, leaders of cultural institutions and organizations, government officials, philanthropists, and researchers. Such partnerships are thriving in Houston, Chicago, New Orleans, Boston, New York City, Seattle, Los Angeles, and Dallas, and they exist also in many smaller urban areas, towns, and rural communities. Fortunately, nearly every district is home to unique cultural resources that can be leveraged to enhance arts education.

Typically, these partnerships also rely on local backbone organizations, which build relationships among various stakeholders, coordinate their efforts, and serve as a hub for information sharing and strategic planning. For example, Young Audiences of Houston facilitated the creation of the city’s Arts Access Initiative; Boston Public Schools’ Arts Expansion Initiative is coordinated by the nonprofit organization EdVestors; and Ingenuity helped design the Chicago Public Schools’ Creative Schools Initiative.

These initiatives vary in their scope and employ a broad range of strategies, of which partnership coordination is one. Other important components include data measurement, outreach efforts to build community support, and advocacy for increased public funding, all of which contribute to offerings such as:

- Professional development opportunities for arts instructors as well as arts-integration professional development for classroom teachers;

- Teaching-artist residencies;

- Field trips to arts institutions;

- In-school performing arts events;

- Afterschool arts programs; and

- Grants to schools and classroom arts instructors to enhance arts education.

The effect of such programming can be powerful in areas plagued by resource constraints and inequities. Not only do partners work directly with school-based educators, equipping them to provide high-quality arts instruction, but they engage with arts organizations and artists to offer enriching complements to the school curriculum. For example, these partnerships might provide students with opportunities to visit a world-class art museum, see a live theater or dance performance, or learn about music from a trained classical musician.

Several of these partnerships also have created sophisticated data-collection systems to help identify local resources and needs. For example, Chicago’s Creative Schools Initiative maintains an inventory of school-level arts programs and levels of instruction, which allows it to pinpoint schools where specific community resources ought to be targeted. Likewise, Boston’s Arts Expansion Initiative and Seattle’s Creative Advantage have assembled user-friendly databases and guides that equip school leaders with easily accessible information on community programs and resources, along with suggestions of how they can best serve particular school needs.

Some of these partnerships also have come up with creative ways to leverage existing resources. For example, New Orleans’s KID smART has drawn upon the city’s immense pool of local artists to create professional development opportunities and arts residencies for local teachers. Dallas’s Big Thought has created an incredibly broad range of arts opportunities across all parts of the district by looking beyond classrooms and schools, reaching out especially to afterschool and summer programs.

- Related: How to increase arts education

- Related: A districtwide commitment to arts integration

- Related: On the goals and outcomes of art education: An interview with Lois Hetland

Universities have proven to be great resources as well. For example, the Houston Education Research Consortium — a researcher-practitioner partnership between Rice University and the Houston Independent School District — has worked closely with the city’s Arts Access Initiative to collect data on student participation and outcomes. Similarly, Los Angeles’s Arts for All has a long-standing partnership with Harvard University’s Project Zero, conducting joint research into what constitutes a quality arts education.

In all, these partnerships have compiled an impressive list of resources and accomplishments, providing a strong hint of their potential to scale up effective and equitable arts education programs across the country. However, we don’t mean to suggest that creating and maintaining such partnerships is simple. Doing so can be complicated and difficult work, and as we describe below, educators and community leaders would be well-advised to keep in mind a number of lessons from the field.

Key considerations for successful partnerships

Key considerations for successful partnerships

While every school-community arts-based partnership has its own unique goals and strategies, successful partnerships share some key strategies as well:

- Secure broad buy-in and support. In addition to reaching out to education officials and arts organizations, successful partnerships tend to engage a range of local stakeholders, including government officials, business leaders, community activists, and philanthropists. Securing funds for arts education resources has been a chronic challenge for schools, particularly for those serving historically underserved student populations. However, the healthy growth of partnerships in various cities suggests that communities are eager to provide students with arts education opportunities — advocates may just have to cast a wide net to find the support they need.

- Be proactive in identifying and addressing potential conflicts. The downside of working with multiple partners is that they are likely to have differing and perhaps conflicting interests and needs. For example, arts organizations often struggle with the expectation that they align their programs and services to the local school system’s curriculum — one large-scale evaluation of school-arts partnerships in Los Angeles found that over half of the participants believed their own needs were not being met adequately due to compromises they had to make (Rowe et al., 2004). Such conflicts may be unavoidable, but they can be minimized if educators and arts professionals identify their needs up front and are willing to keep negotiating them over time.

- Designate an independent body to oversee partnerships. Initially, arts education partnerships may thrive on the grassroots energy and commitment of their founders. Over time, though, maintaining those partnerships becomes impossible unless somebody assumes responsibility to coordinate among the various players, especially in school districts with high teacher and administrator turnover. Without exception, the most successful and enduring partnerships depend on a backbone organization, usually a nonprofit, to facilitate the work, negotiate among schools and cultural institutions, advocate for increased public and private funding, and ensure that local needs are being met.

- Seek out, share, and analyze data. The most successful partnerships make a regular habit of assessing their own strengths and weaknesses, measuring their progress against specific goals, and changing course as needed. Arts organizations and cultural institutions may not have much experience collecting and analyzing performance data, and school systems may not collect or report much data about student performance in the arts. But if they mean to identify and address inequities in students’ access to high-quality arts education, then all partners — cultural institutions, schools, intermediary organizations, and others — must be willing to seek out, share, analyze, and use reliable information about local needs and program effectiveness.

By transferring educational decision-making authority back to the state and local levels, ESSA provides a great opportunity to reverse the decline in arts education that occurred under NCLB. Nonetheless, many schools will continue to struggle with resource constraints unless they can find new funding. The creation of school-community arts education partnerships appears to offer a promising strategy for addressing these challenges, but it should be seen as a way to enhance, not replace, traditional K-12 arts education. A successful strategy requires a blended approach that draws support from the public, nonprofit, and private sectors.

Early indicators provide a reason to be optimistic. For example, since the adoption of Chicago Public Schools’ Arts Education Plan, the number of active community partners serving schools has risen to an all-time high, with 96% of schools having a relationship with at least one partner. In addition, the city has seen steady increases in the number of elementary arts teachers employed in the system, and private funders have increased their giving to programs that promote arts access (Silk, 2016). In Boston Public Schools, too, access to arts learning has increased significantly, including increases in public funding for more in-school arts teachers and buy-in from 70 external partner organizations (Perille, 2016). For high school students, participation in arts education opportunities has more than doubled since 2009, and in 2013, the Arts Expansion Initiative launched a program that enables partner organizations to offer high school students credit-bearing arts education courses that otherwise would be unavailable (Gibson, 2016).

Still, more evidence is needed. One promising development toward that end is a research effort in Houston to evaluate the Arts Access Initiative through a school-level randomized controlled trial. This effort will be the first to rigorously evaluate the benefits of these partnerships and explore ways to improve their execution. Of particular interest is that the leaders of the initiative are committed to evaluating the program across a broader set of outcome measures than standardized test scores alone. As recent studies suggest, access to arts education may help improve graduation rates (Thomas, Singh, & Klopfenstein 2015), critical thinking skills (Bowen, Greene, & Kisida, 2014; Kisida, Bowen, & Greene, 2016), empathy, tolerance (Greene, Kisida, & Bowen, 2014), and cultural consumption (Kisida, Greene, & Bowen, 2014). And if researchers continue to learn more about the effects of arts education on additional outcomes like school engagement, character skills, interest in art and culture, and long-term educational aspirations, this should inform policymakers’ thinking as they consider broader definitions of student success under ESSA.

References

Bowen, D.H., Greene, J.P., & Kisida, B. (2014). Learning to think critically: A visual art experiment. Educational Researcher, 42 (1), 37-44.

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). (2015). 114th Congress. http://edworkforce.house.gov/uploadedfiles/every_student_succeeds_act_-_conference_report.pdf

Gibson, C. (2016). Dancing to the top: How collective action revitalized arts education in Boston. Boston, MA: EdVestors & Boston Public Schools Arts Expansion Partners. www.edvestors.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/BPS-Arts-Expansion-Case-Study.pdf

Government Accountability Office (GAO). (2009). Access to arts education: Inclusion of additional questions in education’s planned research would help explain why instruction time has decreased for some students. GAO-09-286. Washington, DC: Author. www.gao.gov/assets/290/286601.pdf.

Greene, J.P., Kisida, B., & Bowen, D.H. (2014). The educational value of field trips. Education Next, 14 (1), 78-86.

Kisida, B., Bowen, D.H., & Greene, J.P. (2016). Measuring critical thinking: Results from an art museum field trip experiment. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 9 (1), 171-187.

Kisida, B., Greene, J.P., & Bowen, D.H. (2014). Creating cultural consumers: The dynamics of cultural capital acquisition. Sociology of Education, 87 (4), 281-295.

Perille, L. (2016, November 29). A blueprint for successful arts education. Education Week. www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2016/11/30/a-blueprint-for-successful-arts-education.html

Rabkin, N. & Hedberg, E.C. (2011). Arts education in America: What the declines mean for arts participation. Based on the 2008 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts. Research Report #52. Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts.

Rowe, M., Castaneda, L.W., Kaganoff, T., & Robyn, A. (2004). Improving arts education partnerships. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp.

Silk, Y. (2016). State of the arts in Chicago Public Schools: Progress report 2015-16. Chicago, IL: Ingenuity. www.joomag.com/magazine/ingenuity-state-of-the-arts-progress-report-2015-2016/0495510001479939351?short.

Stringer, S. (2014). State of the arts: A plan to boost arts education in New York City schools. New York, NY: Office of the New York City Comptroller.

Thomas, M.K., Singh, P., & Klopfenstein, K. (2015). Arts education and the high school dropout problem. Journal of Cultural Economics, 39 (4), 327-339.

Walker, T. (2012, April 5). The good and bad news about arts education in U.S. schools. NEA Today. http://neatoday.org/2012/04/05/the-good-and-bad-news-about-arts-education-in-u-s-schools-2/

Yee, V. (2014, April 7). Arts education lacking in low-income areas of New York City, report says. The New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2014/04/07/nyregion/artseducation-lacking-in-low-income-areas-of-new-york-city-report-says.html?

Zubrzycki, J. (2015, December 15). In ESSA, arts are part of well-rounded education. Education Week. http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/curriculum/2015/12/esea_rewrite_retains_support_f.html

Originally published in April 2017 Phi Delta Kappan 98 (7), 8-14. © 2017 Phi Delta Kappa International. All rights reserved.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Brian Kisida

BRIAN KISIDA is an assistant research professor of economics and public affairs, University of Missouri, Columbia, Mo.

Daniel H. Bowen

DANIEL H. BOWEN is an assistant professor of educational administration and human resource development, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas.