Brazil has come a long way in improving its public schools, but new reforms that lengthen the school day and improve teaching and compensation are still needed.

The primary challenge facing Brazil is how to improve basic education for all students ages 4 to 17. Only 40% of students who finish 5th grade are proficient in reading and only 36% in mathematics, according to data from national assessments. At the end of the 9th grade, only 27% of students achieve the expected skills and competencies in Portuguese, Brazil’s national language. At the end of high school, no more than 10% of Brazilian students are fully able to deal with the abilities and competencies requested in mathematics. So it is not surprising that Brazil was among the 10 worst scorers in the 2012 ranking of 65 participating countries in the Program for International Student Assessment (OECD, 2013).

Low levels of parental education and social inequities help explain some of the weak performance. Internal school issues also have negative effects on student learning. Students stay an insufficient time in school — about four hours a day, which is not enough to complete the entire curriculum. About 35% of high school students go to school at night and are most often taught by a separate set of teachers because classes are crowded during the day.

Although Brazil’s investment in education reached 5.8% of GDP in 2010, the per student public investment in basic education remains low, an average of $1,250 annually, as compared to an OECD average of $6,240 per student. Besides this low spending, the low quality of Brazilian education seems to be affected by poorly paid teachers who are not engaged and not prepared to improve the quality of education. The best students aren’t motivated to enter the profession because teaching is not an attractive career. Teachers’ colleges are excessively theoretical and don’t prepare teachers for practical classroom issues.

The lack of qualified teachers also affects the high school level. The nation has a shortage of teachers in math, physics, sciences, geography, and foreign languages. The Ministry of Education recently reported that 55% of high school teachers lack specific qualification on the subject they teach. Public schools, which enroll 85% of Brazil’s high school students, have in general unmotivated, poorly paid teachers without the required qualifications to create a good environment for teaching and learning, the report said. This report justified an announcement by the education ministry that it will launch an online teacher training for 490,000 high school teachers.

Reform efforts

Despite such discouraging data, there have been great efforts over the last 20 years to improve education in Brazil. In 2007, Brazil set forth an Education Development Plan (PDE), which amounted to a phalanx of proposals intended to improve how well the country educates its children. The central facet of that plan was creating the Basic Education Development Index (IDEB), a measure of the academic achievement of students in each municipality in the country. The PDE also called for the Brazilian Ministry of Education to focus on quality teaching and learning as national priorities. All of this has led to more efforts by the state and municipal governments to increase investments to improve classrooms, extend the school day, train teachers, improve curriculum, and provide teacher coaching. Brazil also has increased its effort to expand early childhood education.

One of the most positive efforts has been mobilizing civic groups, nonprofits, media, and other organizations to push for effective education reforms. Nongovernmental organizations and independent associations are developing research projects to improve the quality of public schools. The mass media and the press are looking to education as a major issue on the national agenda.

Some nongovernmental organizations are supporting states and municipalities to implement full-time secondary schooling. The Institute of Educational Co-responsibility (ICE) is one such group that’s been working toward that goal and other public school reforms since 2001, starting in Pernambuco state in Brazil’s northeast quadrant. As part of its effort, ICE has developed a new pedagogical model that enhances the role of students in the learning process and a new model of curriculum standards integrating instruction with active learning projects. ICE (www.icebrasil.org.br) is headquartered in Recife, the Pernambuco state capital, and is funded by the government and private foundations.

Expanding its reach

ICE’s pedagogical model differs from the Brazilian standard because it is student centered. That is, the model seeks to promote autonomy and leadership of young people in their learning process In addition, ICE’s school management model is ahead of Brazilian standards because it’s based on coordinating all school processes, monitoring results, and involving the whole school community. Thus, the ICE model intends to form a culture of evaluation in the schools.

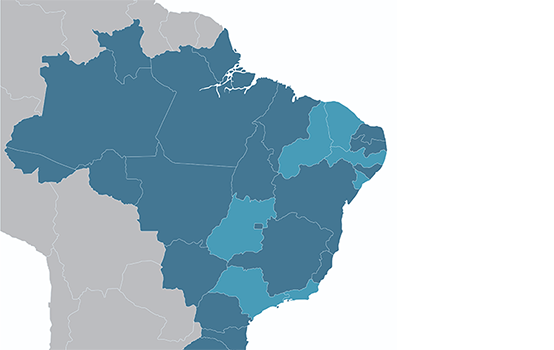

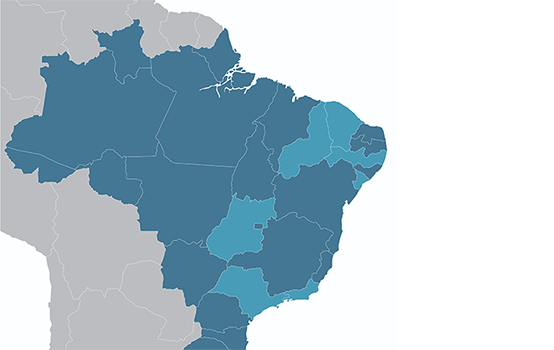

This innovative ICE method reaches almost 500 public schools in seven of Brazil’s 26 states (Pernambuco, Ceará, São Paulo, Goiás, Piauí, Rio de Janeiro, and Sergipe). By the end of 2014, ICE anticipates that 160 more schools will have implemented its methods. More than 350,000 students attend ICE schools, which operate with seven hours of instruction daily by teachers who receive higher salaries and other incentives than teachers who are not involved in the program.

Empirical evidence shows that in Rio de Janeiro the IDEB of ICE schools increased 36% between 2009 and 2011, while the IDEB of regular public schools operating the standard model in Rio increased by only 11%. Although the data do not allow claims of causal impact of the ICE model, the results are still impressive and make this experience one of the most promising in Brazil.

A new vision in Brazil

A future vision of Brazilian education necessarily means promoting radical changes in teacher training, professional development, and compensation, as well as implementing a standard national curriculum, reforming secondary schools, and increasing the school day. Some states — such as São Paulo, Pernambuco, and Minas Gerais — have launched policies that promote merit-based bonuses, which have met with teacher union resistance. Other necessary reform measures include increasing the quality of early childhood education, reforming the Brazilian high school system, expanding technical education, and improving university education in an effort to equip citizens with new skills, an ability to handle new information technologies, and scientific literacy.

What the new Brazilian education calls for is quality basic education, well-paid, merit-based teachers, and focus on the role of education in society. The major challenge is to convince parents and teacher unions about the urgency of these educational reforms.

- Related: Global voices Malaysia: A global effort for educational equity

- Related: Global voices India: The true gift of education is more giving

- Related: Global voices Burkina Faso: Two languages are better than one

- Related: Global voices Haiti: Making education a right

- Related: Global voices Israel: Helping underprivileged children succeed

- Related: Global voices Russia: Russia’s own Common Core

- Related: Global voices Australia: Can schools compete?

- Related: Global voices Japan: Good teaching goes global

- Related: Global voices | France: Leadership lessons for French educators

Reference

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2013). Results from Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2012. Paris, France: Author.

Citation: de Castro, M.H.G. (2014). Global voices | Brazil: A new agenda for Brazilian education. Phi Delta Kappan, 95 (7), 76-77.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Maria Helena Guimarães De Castro

MARIA HELENA GUIMARÃES DE CASTRO .