Given the seriousness of the pandemic and the intense political debate surrounding school reopening, journalists need to work extra hard to avoid fanning readers’ fears.

By Alexander Russo

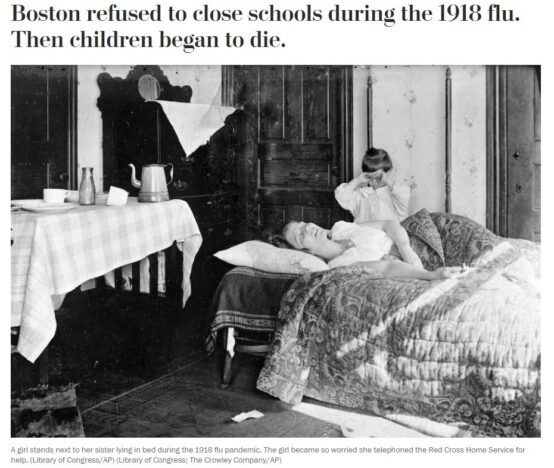

Last week, Boston Globe education editor Sarah Carr criticized a Washington Post story headlined Boston refused to close schools during the 1918 flu — then children began to die for its over-the-top treatment of the scary topic that’s dominated news coverage lately:

“While the health risks and precautions of reopening schools need to be taken very very seriously — and there are some valid arguments for not doing it at all — the framing, timing and headline of this story seem needlessly alarmist,” wrote Carr about the piece, which among other things failed to clarify that COVID-19 is much less likely to kill children than the Spanish flu.

But Carr’s comment also raises an important question for education journalists: how to convey serious risks and strong emotions that surround the heated reopening debate and inevitable reports of school-based infections without unnecessarily (or misleadingly) fanning readers’ fears?

That’s not an easy task, given the seriousness of the situation and the intensity of the politics. But careful, contextualized reporting is all the more necessary when the stakes are so high and the debate is so polarized.

“While the health risks and precautions of reopening schools need to be taken very very seriously — and there are some valid arguments for not doing it at all — the framing, timing and headline of this story seem needlessly alarmist.” – Sarah Carr

The Post story is far from the only instance in which school reopening coverage could be described as needlessly alarmist, which I’m defining as emphasizing danger and emotion at the expense of context and data.

Earlier this month, the Times published a story headlined A School Reopens, and the Coronavirus Creeps In. Its depiction of events at an Indianapolis area high school were overheated and decontextualized in several ways — starting with the horror-movie headline.

A widely shared mid-July New York Times story, Older Children Spread the Coronavirus Just as Much as Adults, Large Study Finds, was based on a flawed Korean study and made claims that have not stood up to scrutiny. The Times recently published an updated story about the research.

An early August Washington Post story opened with the statement that “most American parents think it is unsafe to send their children back to school.” However, the poll results presented in the story show that, while nearly 40 percent of American parents think it’s unsafe to send their children back into school buildings, roughly 60 percent favor a return to some form of in-person instruction, full time or hybrid.

Some of the other incidents that turn out to have been overdramatized in much of the early coverage include the outbreak of cases at a Georgia camp, the cases that showed up in Israeli schools, and the childcare cases in Texas this summer.

Here’s the Washington Post story that Carr identified as needlessly alarmist.

Here are some helpful ways to convey the very real risks of infection and transmission without making readers think that reopening in-person instruction will inevitably lead to a public health disaster:

CONTEXTUALIZE THE NUMBERS

Don’t just give readers a raw number without telling them the larger context. Don’t just give them a percentage increase without telling them the raw numbers, either. Without numerical context, readers may make mistaken assumptions about the situation.

Polls and other forms of data can also tell us more than anecdotes, which should be the color around real data. The most recent Gallup poll shows that a lot more parents nationwide want their kids on full-time remote learning than a couple of months ago — but still, a strong majority want SOME kind of campus presence for their children.

Infection rates vary widely from state to state, community to community, even neighborhood to neighborhood. So do the thresholds that have been set by local officials to reopen schools in person. Be sure to tell readers what the local rate is so that they’re not universalizing the story you’re telling them. (At present, 19 states meet the 5 percent World Health Organization threshold for community reopening, according to Johns Hopkins.)

CONTEXTUALIZE ANECDOTES AND QUOTES

Vivid anecdotes are great, but don’t just present them to readers without information about what they represent. Are they typical cases or outliers?

Dramatic quotes are important, too. Go ahead and use them, but then contextualize what’s being said. Does the sentiment being expressed match the research?

Coverage that relies or focuses too much on school infection anecdotes and vivid quotes runs the risk of readers assuming that the situations and feelings being expressed are representative. Why else would you be including them?

PROVIDE BACKGROUND INFORMATION

One easy way to limit the danger of perpetuating unnecessary concern is to fight back against efforts to juice up your story (including the headline). What’s happening out there is dramatic enough; it doesn’t need that kind of amplification.

In pretty much every reopening story, it’s important to convey to readers the infection levels in the surrounding community, whether the schools being described are following widely agreed-upon protocols, and if it’s been established that transmission of the infection on campus has occurred. Otherwise, readers may assume that school-based infections are spiking, that transmission is taking place, or that safety protocols were ineffective.

The reopening options aren’t binary and shouldn’t be presented as if they are. Parents who need to go back to work and can’t supervise remote learning will find family to take care of children, or leave them home alone, or send them to childcare facilities. Some districts that are going remote only are offering childcare and some supervised remote learning in school buildings. Teachers in some places are threatening to strike, while others are participating without widespread protest.

This New York Times story featured a horror-story headline and a lack of contextual information.

I’m sure that there are many who take the opposite view that media coverage has downplayed the risks of in-person reopening, endangering students, teachers, and parents.

But that’s not what I’ve been seeing or hearing from the researchers and health experts I’ve spoken with. I’m also not the only journalist expressing concerns about the coverage being produced. Freelance writer David Zweig has stories published in WIRED and the New York Times that question the narrative around school reopening. ProPublica’s Alec MacGillis has been raising a series of coverage concerns on Twitter. And The Atlantic’s Ed Yong noted in a recent overview of the nation’s flawed response that media coverage had “added to the confusion.”

Adding to the confusion is not something that education journalists should want to be a part of. So the next time you’re writing about school reopening, try some of these strategies and see how they work. Finding the right balance between conveying real risks and reminding readers of important contextual factors is difficult but important. Scary as it may be to break away from the stories that your competitors and colleagues are all writing, there can be enormous power in writing something different.

Previous commentary:

Smart ways to cover the wrenching debate over reopening schools

Reopening coverage should focus on students’ needs

Misleading coverage of school shootings in 2018

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alexander Russo

Alexander Russo is founder and editor of The Grade, an award-winning effort to help improve media coverage of education issues. He’s also a Spencer Education Journalism Fellowship winner and a book author. You can reach him at @alexanderrusso.

Visit their website at: https://the-grade.org/