Contributing editor Amber C. Walker reflects on how her experiences as a student shaped her perceptions and beliefs as a journalist, and urges others to do the same.

By Amber C. Walker

I sometimes wonder where I would be today if my kindergarten teacher hadn’t encouraged my mother to have me take the admissions exam for Chicago’s selective elementary schools.

That one test result earned me a coveted spot at Edward W. Beasley Academic Center, one of the city’s gifted and talented elementary programs, where I matriculated to one of the top-performing high schools in the country.

And that, in turn, set the foundation for me to become the first person in my immediate family to graduate from college, earn my master’s degree, travel the world, and earn a decent, fulfilling living. If I have children of my own, they will likely attend high-performing, well-funded community schools.

As an adult covering K-12 education, I find that my experience also shaped my belief that if students, no matter their backgrounds, are treated with dignity and are provided with educational spaces where they feel safe to take risks and be vulnerable, coupled with the tools and resources they need to absorb the curriculum, they will succeed academically.

It is not easy, but it is possible. I’ve seen glimpses of it during my time learning in, teaching in, and writing about classrooms.

My experience shaped my belief that if students, no matter their backgrounds, are treated with dignity and are provided with educational spaces where they feel safe to take risks and be vulnerable, coupled with the tools and resources they need to absorb the curriculum, they will succeed academically.

If things had gone another way, my entire educational experience would have fit into a two-block radius in some of Chicago’s most academically disadvantaged schools.

I would have gone to Parker Community Academy, which the neighborhood folks call “Big Parker.” According to Parker’s most recent Illinois school report card, only 8% of students met expectations in language arts and 3% in mathematics.

Behind Big Parker was Robeson High School, consistently ranked as the worst public high school in Chicago. Robeson closed in 2018, along with three other high schools in Englewood, as Chicago Public Schools decided to consolidate the under-enrolled neighborhood high schools under one roof in a new building.

If I had been one of the 40% of students to graduate from Robeson in 2007, I likely would have attended Kennedy King College, a community college a half-mile down the road.

If things had gone another way, my entire educational experience would have fit into a two-block radius in some of Chicago’s most academically disadvantaged schools.

When my mother enrolled me at Beasley, an elementary magnet program named for the first African-American pediatrician to practice at what is now known as Northwestern Memorial Hospital, she believed I would get a better education there than I would at the neighborhood schools.

Still, it irked me that I could not go to school in my neighborhood.

In my 6-year-old mind, a school was a school, so why did I have to wake up earlier than other kids to go to mine, which was about 3 miles from my home?

Although I saw my Englewood peers as smart kids who showed leadership, intellect, talent, and potential, that mindset was not sown into them in the same way my classroom experience made it crystal clear for me.

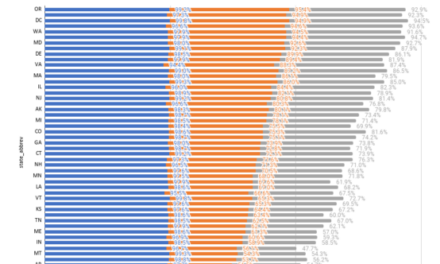

I felt like an anomaly not attending my neighborhood public school. Fast-forward 25 years, it’s the reality for 90% of Englewood’s high school students. This mass exodus from neighborhood schools to charter schools and CPS schools outside of the area also exists, though not as pronounced, at the elementary level.

As an education reporter, it is clear to me that Englewood’s schools are not inherently bad, but decades of neglect and divestment by the district and the city created these student outcomes, not the perceived shortcomings of a community and its kids.

Although I saw my Englewood peers as smart kids who showed leadership, intellect, talent, and potential, that mindset was not sown into them in the same way my classroom experience made it crystal clear for me.

In 2003, I entered Walter Payton College Prep High School, which my mother insisted was the best choice because I’d be exposed to a more diverse student body (Beasley was majority African American while Payton boasted a nearly equal mix of Black, white, and Latinx students) and it was a brand-new, state-of-the-art selective school.

I eventually warmed up to Payton and would share stories with my friends from Englewood about how challenging my classes were, the fancy stores and buildings that occupied the affluent neighborhood surrounding it, and how I was adjusting to meeting folks who lived in every corner of the city from a multitude of racial and socioeconomic backgrounds.

My Englewood peers were grappling with overcrowded classrooms, the loss of longtime teachers, and the deaths of classmates from gun violence in the community.

My Englewood peers were grappling with overcrowded classrooms, the loss of longtime teachers, and the deaths of classmates from gun violence in the community.

Although I appreciated the excellent education at Payton, many of my Black peers and I grappled with the effects of being stereotyped by faculty and other students.

My freshman year I was essentially perp walked from a classroom to the principal’s office by a chemistry teacher who refused to let me enroll in his 10th-grade class, although I’d earned credit for the freshman biology class from my middle school. The administration offered no recourse.

During my junior year as I worked with a guidance counselor on my college application planning process, he dissuaded me from applying to my choice schools, despite exceeding their GPA and test score averages, saying they would be too difficult for me. Instead, he encouraged me and other Black students to focus on Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU’s) since they would be a better social and academic fit.

I also faced countless microaggressions from white, wealthy peers about everything from my hair (which I cut in 11th grade to start my first set of locs), to my clothes not being expensive enough, to being from Englewood.

The day our ACT scores were released, one of my white male peers made it a point to ask the Black students what we got as a way to make himself feel better about his score. He was disappointed to find out that many of us had scored higher than him.

Despite the school’s diversity, most of my friends were other Black and Latinx students because those were the only folks I felt comfortable enough being authentic around. About a decade after I graduated, the racial issues experienced by Payton students made national headlines.

From these experiences, as well as my time as a classroom teacher and an education reporter, I know it is not enough to have skilled instructors teaching without a healthy school culture and climate.

As reporters, we have to dig deep enough to uncover the systemic, unconscious factors that might be at play.

From these experiences, as well as my time as a classroom teacher and an education reporter, I know it is not enough to have skilled instructors teaching without a healthy school culture and climate.

The sum of my educational experiences was a driving factor for me to pursue teaching and, eventually, education reporting. In both endeavors, I sought to illuminate how systems and history directly influence students’ educational outcomes.

I don’t think of myself as exceptionally gifted. I was just given a shot when I was 5 years old that changed the trajectory of my education and my life. I was lucky to attend a child-parent center, a successful early childhood model aimed at students from low-income neighborhoods that prioritized literacy and parental involvement in the classroom. I was fortunate to have a mother with a work schedule that allowed her to meet the school’s requirements.

All of these happenstances snowballed to get me to where I am today. I want to get beyond “happy accidents” to ensure that all kids, no matter where they are from, can access a quality education.

Previous pieces from Amber C. Walker:

Improving source diversity in education journalism

Introducing Amber Walker, The Grade’s new columnist & editor

What it’s like being a rookie education reporter

Writing great profiles in the age of remote reporting

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Amber C. Walker

In addition to being a consulting editor and columnist for The Grade, Walker is a multimedia journalist and digital content strategist. You can find her @acwalker620 across platforms.