The veteran NPR reporter shares proud moments, frustrations, and advice from his long tenure covering education.

By Kristen Doerer

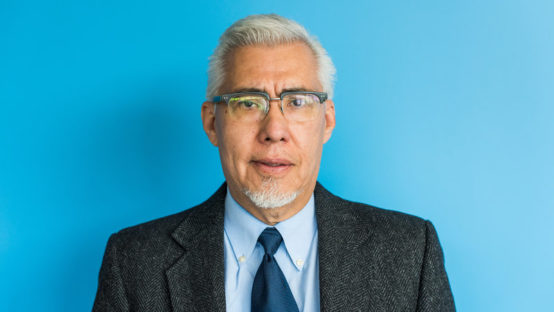

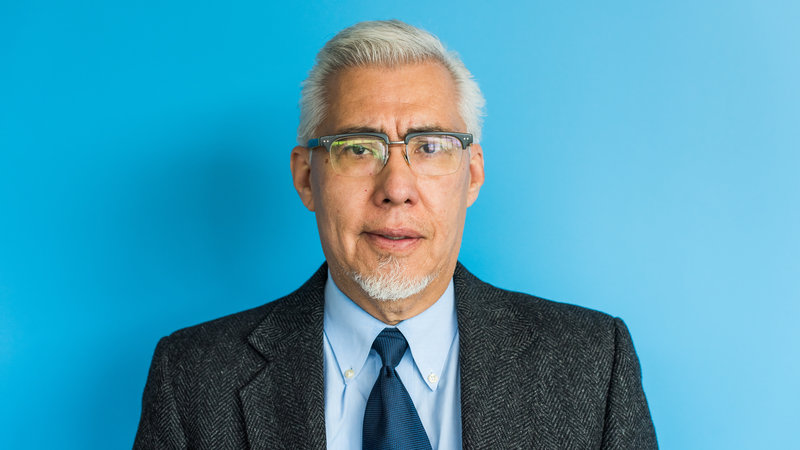

Claudio Sanchez retired in January, after gracing National Public Radio’s radio waves for 30 years with his spellbinding narration and dulcet voice.

Raised in Nogales, Mexico, Sanchez began his career on the U.S.-Mexico border, first as an elementary and middle school teacher and later as the executive producer for the Latin American News Service. He began as an education reporter at NPR in 1989, based much of that time in Washington, DC. Despite other outlets’ offers, Sanchez says he stayed there for three decades because NPR allowed him the flexibility and editorial support to tell the stories he thought most needed to be told. Those included stories on deported students facing challenges in a Tijuana school, the return of bilingual education to California, and the student loan crunch in 2008.

It’s rare to find a reporter who has covered one beat, especially education, for so long — and it’s even rarer for them to have done so for one outlet. So what wisdom does the veteran education reporter have to impart to the rest of us?

While the award-winning journalist is reluctant to prescribe how others should best report on education, he is happy to share his experience. In an interview spanning more than two hours, Sanchez answered my questions with stories of his own reporting, illustrating not only a long and robust career but also a love for storytelling.

In the following interview, he highlights the voices that he says matter most — students’ and parents’. He shares the story he’s most proud of, as well as some candid regrets, and what wisdom he hopes to impart to up-and-coming education reporters.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Sanchez announced his retirement in late January, after 30 years covering education for NPR

Kristen Doerer: What do you think has changed the most in the three decades that you’ve covered education?

Claudio Sanchez: I’m not so sure that things have changed that much. This is a field where trends come and go. Promising practices or policy are never given a chance because we all want immediate results. And so reporters are left with this sense that whatever you’re reporting on really won’t have a shelf life, so we come back and recycle our ways of reporting. And it’s just not healthy — for the journalists or for the public that’s relying on us for information that they can trust about their kids their children. Unfortunately, in my 30 years on the beat, I’ve seen education become a cultural battleground for competing interests. Sometimes [reporters] feed this monster called cultural wars, and we feed all kinds of agendas and politics.

KD: How did you try and avoid contributing to that dynamic?

CS: I always thought covering education out of D.C. was wrongheaded. I just thought that this is too much of a bubble. Not long had I been in D.C. covering education, I said to my editors, the last thing I want to do is go up to the Hill and cover hearings about education. It’s such a waste of time talking to these people who are so far removed. Even people on the right or the left who may have good ideas are living in a time warp because in our real America, the real world, things didn’t work the way they thought.

I very quickly said to my editors, “I want to be able to travel and get out to really concentrate on stories that make a difference and that have some relevance and some impact on a community in a town or a state.” I have to give NPR credit for saying, “OK, fine. Here’s your travel budget.” And I began to gravitate to the stories that I often identified with, which were stories about immigrant families, which is what my family background was. Why is it in this country we see kids as expendable? I tried to answer that question in every story I did.

KD: Sometimes politics in education stories are inevitable. How do you inform the public about them without amplifying them?

CS: I often think that’s in large part the editor’s job. A reporter often comes back with a really juicy story with lots of politics. An editor I think should watch out for and be able to advise a reporter, “Look. You’ve got all these legislators chiming in on the policy or on the cost, and you’ve got a governor who’s peddling some program or some policy to deal with dropouts. But where are the kids? Where are the teachers?” And reporters have to catch themselves. They have to say “Well, I’ve got a juicy story, but am I missing the forest for the trees?”

To learn more about how the media covers education, follow The Grade on Twitter and Facebook.

Here’s a 1998 interview with Sanchez in Phi Delta Kappan magazine

KD: What wisdom do you want to impart to young, up-and-coming reporters?

CS: In our search for “balance” in our stories, we often neglect fundamental truths about the triumphs and failures of our public education system. Education reporters too often become purveyors of the “tit-for-tat” journalism that clarifies nothing and serves no one.

I’ve learned that kids take a backseat to adults’ agendas. Too often, education, as a political issue, has been used as a blunt instrument with which to pummel an adversary, leaving a trail of casualties in its wake. We must not allow our stories to be misconstrued in support of political and ideological agendas — especially if they hurt kids. When that happens, we are complicit. The result? School choice, school funding, immigrant kids, the achievement gap, college access and so many other challenges we face don’t unite us. They divide us.

When I talk to other young reporters, I say to them, “When you write a story, try really hard to end the story with a sense of hope. Don’t let people feel like things are so hopeless, [that] it’s not worth their time worrying about their story or their community or their kids. You have to instill that.”

You could argue, well, that’s not a reporter’s job. A reporter’s job is just to report the facts, to give people accurate information about the community or policy or whatever. But I don’t know. I would argue that you leave people empty-handed if you don’t offer a perspective [of hope] in terms of the people you choose to put in your story.

KD: What advice would you have given your younger self?

CS: If I had known then what I know now, I think I would have been a little bit more aggressive and adventurous with stories I did, and not have settled for, you know, kind of piecemeal stories. I would have done less stories about policies about Congressman or Governor XYZ pushing or peddling some reform that in the end never mattered. Certainly, I would have talked less to all those think tanks that have their own agendas, especially in D.C. And certainly, a big one would be questioning the research, and not letting it drive coverage or drive the way you approach a sorry. To be not cynical or jaded, but to be skeptical.

KD: What was your favorite part about reporting and telling these stories?

CS: Oh, just talking to families and children. It just brought me back down to earth, sitting in a living room with someone or over the kitchen table, meeting in a parking lot with parents, going to a teacher’s house. I often try to get interviews with people outside of the school environment. I just realized that the setting often contributed to how free they felt in really telling you their story. And if you were talking to kids, the last place where you wanted to talk to them was at school.

It was always like peeling an onion. You just slowly but surely, if you did your job right, you would peel back the layers and layers and layers of stories. Eventually, you hit the spot and you wouldn’t have gotten there unless you had been talking to them for an hour or two.

Sanchez sharing his reporting wisdom at a recent conference.

KD: What story are you most proud of? And do you have any regrets?

CS: The one regret I kind of alluded to was not having done in my first seven years, what I did in the middle of my career and up until now — to really have honed in on the reason kids fail, which often is not their fault. And not having done more to explain the true reasons or the reasons why poverty may not be destiny but it’s a hell of a reason why kids and families don’t take advantage of school.

The proudest story that I can remember was in my first year reporting for NPR. It was a story I did when the first President George Bush had adopted the [Reagans’ Just Say No to drugs] slogan as well. The White House was going to pipe that message into all these school districts, 16,000 school districts. I went to Spingarn High School in D.C., a struggling school, to sit in on this speech and get the reaction from kids. I remember just sitting there with my mouth open about the story these kids had to tell. And there was one young woman who broke down very quickly. She said, “I know what the president is trying to do. And the message he’s trying to give us. But he doesn’t live where I live. He wasn’t there last night when my mother” — and I’m paraphrasing here — “When my mother took me and my little sister out to the street to hold on to the drugs that she was selling. She wasn’t there the next day when I had to take my little sister to school. And I thought about running away. But I can’t because I can’t leave my little sister behind. Drugs have taken over my neighborhood. Our Deacon at church is on drugs. Just about every friend I have is on drugs. The neighbors. It’s easier to buy weed or crack than it is to buy a gallon of milk.”

That’s the story we put on the air. There was only me saying, “Today, the president delivered a message to the youth of America, and here’s how some kids reacted in Washington D.C.” And then it was the voice of this one young girl. The reaction was overwhelming.

KD: In the past 30 years, has there been an improvement in covering immigrant communities in education?

CS: No, absolutely not. To me, it’s ironic. I have to be honest. Up until recently, I don’t think NPR covered immigration well. In fact, we did away with the immigration beat for a period of time. It’s ironic because the demographic shift in our schools is obvious; it’s there for everyone to see. And this country — at least our schools are so ill-prepared for it. And I think that what keeps schools and reporters from addressing some of the more pressing problems having to do with immigrant kids is the larger debate about xenophobia in this country.

KD: Is this lack of coverage partially an issue of the lack of diversity among education reporters?

CS: It’s pretty clear we’re not nurturing enough, we’re not growing enough reporters of color. More important than the diversity question, or as important, is where are we training these reporters? You have to wonder what is it that those organizations are doing to attract more diversity. What are they offering? And then in trying to build a diverse group of folks, we have to make sure that the diversity is not just racial or ethnic, but diverse also in terms of background.

Sign up here for the week’s best education news and newsroom comings and goings.

In the last couple of years, Sanchez has circled back to some of the stories and characters from his earlier reporting. For example: A Kindergarten Story, 13 Years Later.

KD: Are there any stories that you think that the education beat should be covering? Or are there any angles that we are missing in our coverage?

CS: We should be doing more reporting about things that matter but that we’re not doing. Here’s a good school that’s doing the right thing and raise the question in your piece: why isn’t that school down the street doing the same thing? And hopefully there’s an answer for that. I find that when you get parents involved in stories, parents are the ones hungriest for solutions.

We’re also missing the stories of parents. I think they’ve been left out of way too many education stories. I initially was saying you don’t know you don’t have kids’ voices. I would say that parents are a close second. Because most people can identify with the positions that parents can take.

KD: Why did you decide to retire?

CS: I don’t know the answer to that. Truly. I liked finding new ways to do stories, but I guess I had an inkling that what was really bearing down on me was looking at the daily diet of news and being frustrated by the things I had to cover. Not that my editors were saying you have to cover, but that we were obligated to cover, whether it’s Secretary DeVos, Senator Alexander on the Hill peddling some plan for higher ed, or Governor XYZ’s next school reform plan, or how last year’s election brought in more teachers, or the teachers strike. To me, those began to feel very tedious. I guess my answer is it became harder to dig into a new angle — although I think they’re there. There are definitely ways to cover them in very fresh news ways. It just became more of a task — a little harder to do. But I have to say that having made the decision I thought: Am I leaving at the right time? Because there’s so much more work to do.