Widespread media reports about “record” numbers of educators running for office seem increasingly questionable. How did that happen? Why does it matter?

By Alexander Russo

While we wait for the results of today’s voting, let’s take a few minutes to consider media coverage of education issues leading up to Election Day 2018.

No doubt, there has been a lot of midterm-focused education coverage in the past few weeks and months – much of it quite interesting and useful.

But it hasn’t been as accurate as it should have been at times — in particular when it comes to writing about the “record number” of educators running for office, which has become something of the dominant narrative in the last few weeks.

A number of outlets — Vox, Christian Science Monitor, and Associated Press among them — have reported seemingly large numbers of educators running for office in 2018, based on numbers provided by the National Education Association.

However, the facts do not point to “record” numbers of educators running for office in 2018.

According to the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee, using a similar grab-bag definition including of administrators and former educators, there was actually a slight decline from two years ago.

And the real number, at least for current teachers, doesn’t appear to be anywhere near as high.

Education Week, which has been reporting on current teachers running for state legislature, has focused on 180 current teachers running nationwide.

Nearly 1,500 Teachers Are Running For Office In November’s Elections HuffPost 10/24

For weeks now, it seems, national media outlets have reported ever-increasing numbers of educators running for office in the 2018 midterms, usually based on data provided by the NEA.

An early October story from the Associated Press reported that the number of educators running for office “far exceed[ed] educator candidacies prior to this year’s #RedForEd protests.”

On October 22, the Christian Science Monitor reported “record numbers of educators on ballots in the general election,” citing National Education Association figures showing candidates for state office.

A CNBC story from October 31 reported that the number of educators running for office was “more than double the 2014 and 2016 numbers.”

On that same day, Vox reported that last spring’s teacher strikes pushed “a record number of educators” to run for office. The number is later described as “more than triple the number who usually run for office in an election cycle.”

“Teachers running for office in record numbers, motivated by low pay and education cuts,” claimed a November 2 USA Today story.

You get the idea.

Few of those relying on these figures seemed to question the numbers being reported by the NEA, ask how they were collected and compiled, or even wonder what the previous numbers were.

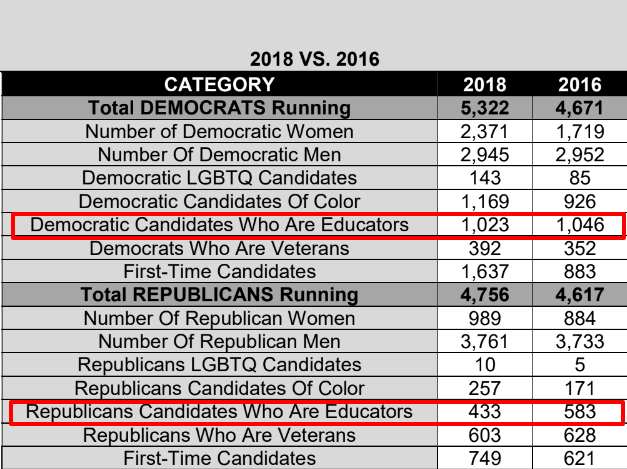

Screenshot from an undated DLCC “diversity report” showing fewer educators running for office in 2018 compared to two years ago.

This storyline came under scrutiny last week when Wall Street Journal national education reporter Michelle Hackman shared information on Twitter from the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee (DLCC) showing that fewer educators are running for state legislature in 2018 than did two years ago.

There are several similarities between the DLCC and NEA lists. Both include K-12 administrators and college professors, not just K-12 teachers. Both are focusing on candidates running for state legislature, not any other kinds of elected positions.

Both lists include both current and former educators. And neither includes non-legislative and local nonpartisan elections such as educators running for local school boards or educators running for Congress.

Perhaps as a result, the raw DLCC numbers differ only somewhat from the numbers being provided by the NEA. The DLCC reports fewer than 1,500 educators running for state legislature in 2018. As of Friday, the NEA was estimating that the total number of educators running totaled 1,779.

But the DLCC numbers paint a very different picture than the media narrative around “record” numbers of educators running for office. The DLCC numbers describe a small decline in educators running for state legislative office in 2018, compared to 2016.

How did media outlets decide to go with the NEA numbers and describe them as record-breaking increases? We don’t know.

The NEA claims only that the wave of educators running for state legislative office is “unprecedented.” But the NEA materials do not provide any information about previous campaigns. I’m told that the organization has no baseline data.

At least one education reporter acknowledged the possibility that media coverage may have gotten off track.

“Record numbers of educators are running in walkout states,” tweeted New York Times national education reporter Dana Goldstein in response to the DLCC numbers. “But the claim of a nationwide trend does appear to be vastly overblown.”

The Vox version of the “record” numbers storyline

Media coverage telling an oversimplified story based on iffy data isn’t, alas, an isolated occurrence.

Another example that comes to mind is school gun incident coverage, which turned out to have been based on flawed federal data that some outlets used without verifying its accuracy.

It took an independent effort by NPR to reveal that many of the incidents reported by the federal government and eye-popping numbers shared with the public were inaccurate or hadn’t taken place.

Over-abundant and overheated coverage of school gun deaths this year also made it seem to the public as though students were much more likely to die in schools from guns than actual data would indicate. While tragic and enormously upsetting, school gun deaths remain highly unusual.

Large or small, instances where media coverage exaggerates or misrepresents the facts have several consequences. They undercut public confidence in journalism. They result in exaggerated fears and perceptions (such as fears of being shot at school). They encourage misallocation of funds. They also tend to push out opportunities to delve into more thorough, thoughtful approaches.

Each week, The Grade takes a deeper look at education journalism. Sign up for the free newsletter.

To be fair, many of the articles that have focused on the “record” numbers of educators in state legislative races have been written by reporters who do not regularly cover education.

They may not have debunked the story early on, which would have been my first choice, but fulltime education reporters and national outlets like the New York Times, Washington Post, and NPR seem to have avoided producing similarly problematic stories.

And a few outlets have figured out ways to write about teachers running for office in insightful and interesting ways.

For example, Arizona public radio station KJZZ produced a thoughtful piece about newcomers and incumbents with education connections, breaking out primary winners into multiple subgroups including policy experts and nonprofit employees.

And Education Week took a very different approach, focusing on solely on current classroom teachers and doing its own reporting. “We wanted to be able to cite our own vetted analysis in all of our stories,” reporter Madeline Will told me via email. “So we built a database of current classroom teachers running for state legislature.”

But it’s hard not to wish that there were more terrific stories that could have been gleaned from the data about educators running for office if it had been examined more carefully.

For example, I’d be extremely curious to know more about unexpected states with spikes in educators running for office, or the breakdown of challengers versus incumbents who are also educators.

And what about the 30 percent of educators running for office as Republicans, a chronically under-covered part of the education world? Who are they and what motivated them?

It would also have been enormously interesting to compare educators running for local school board positions to state legislative races. Did more educators run for state legislative positions than for school board – and if so, why?

The long-term problem with simplistic and inaccurate storylines is that they spread misleading information to the public. But the most immediate consequence is that they preclude deeper, more interesting coverage that might otherwise have occurred.

Related posts:

‘Complicating the narratives’ in education journalism

Praise & criticism for media coverage of MA’s $41M charter school ballot debate

School board race reveals chronic gaps in political coverage

Make [education] reporting great again

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alexander Russo

Alexander Russo is founder and editor of The Grade, an award-winning effort to help improve media coverage of education issues. He’s also a Spencer Education Journalism Fellowship winner and a book author. You can reach him at @alexanderrusso.

Visit their website at: https://the-grade.org/