Teacher dissatisfaction is causing more turnover at rural schools compared to urban and suburban schools, and recruitment strategies alone won’t address the issue.

Perennial teacher shortages — including those education is experiencing post-pandemic — receive a great deal of attention. It is widely believed that such teacher staffing problems are primarily due to an insufficient supply of new teachers in the face of two large-scale demographic trends: increasing student enrollments and increasing teacher retirements due to an aging workforce.

The prevailing policy responses to school staffing problems have focused on increasing the supply of new teachers through a wide range of initiatives. Underlying these initiatives is the common assumption that school staffing problems are due to inadequate numbers of newly qualified teachers, and hence, the best solution is to increase that supply.

But are these initiatives coming at the problem from the wrong angle? To answer that question, we need to understand the reasons for shortages.

Understanding teacher shortages

Teacher shortages are not new. For most of the past century, they have come and gone again and again in the U.S. education system. However, since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, teacher shortage concerns have dramatically escalated. It has been widely predicted and reported that the stress brought on by the pandemic spurred a drop in the supply of new teachers and a surge in the departures of existing teachers. However, it remains unclear how these current staffing problems compare to those of earlier decades. The available evidence since the pandemic began has been mostly limited to data from specific states and locales. Until recently, there have not been large-scale national data available to determine how widespread and how deep teacher staffing problems have become in recent years.

Over the past three decades, our research teams have used large-scale nationally representative U.S. Department of Education data to examine teacher demand, supply, turnover, and shortages (e.g. Ingersoll, 2001; Ingersoll & Perda, 2010; Ingersoll et al., 2019; Ingersoll & Tran, 2023). Recently, we decided to focus on rural schools. Research and reform on teacher shortages and turnover has tended to focus on schools in urban areas because of an assumption that schools in those settings suffer from the most serious teacher staffing problems. However, some researchers and reformers have argued that rural schools represent an important, but neglected, segment of the population of schools, students, and teachers. In this view, rural education exemplifies a case of “spatial injustice,” where inequities and deficits in key resources, such as local funding and adequate teacher staffing, are deeply rooted in geography (Tieken, 2017; Tran & Dou, 2019; Tran et al., 2020).

A focus on rural schools

In our new analysis, we looked at national data to provide an overall portrait of teacher staffing problems and turnover in rural schools across the nation. Our method is comparative, focusing on rural schools and comparing them to urban and suburban schools. Our main data source is the nationally representative Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS); its successor, the National Teacher Principal Survey (NTPS); and their supplement, the Teacher Follow-Up Survey (TFS). These data are collected by the Census Bureau for the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the data collection agency of the U.S. Department of Education. Together, these are the largest and most comprehensive data sources available on teachers in elementary and secondary schools. NCES has administered these surveys regularly from the late 1980s to 2021.

Our analyses revealed six key findings, which bolster the argument that rural schools suffer from serious teacher staffing problems. It is important to note that the most recent data we analyze were collected in spring 2021, one year after the pandemic began. Other data we analyze are from earlier years. Hence, our data may or may not reflect all the changes wrought by the public health crisis. Our hypothesis is that our findings, and the trends we uncovered, have continued over time and will become even more pronounced in the future.

The rural school sector is shrinking.

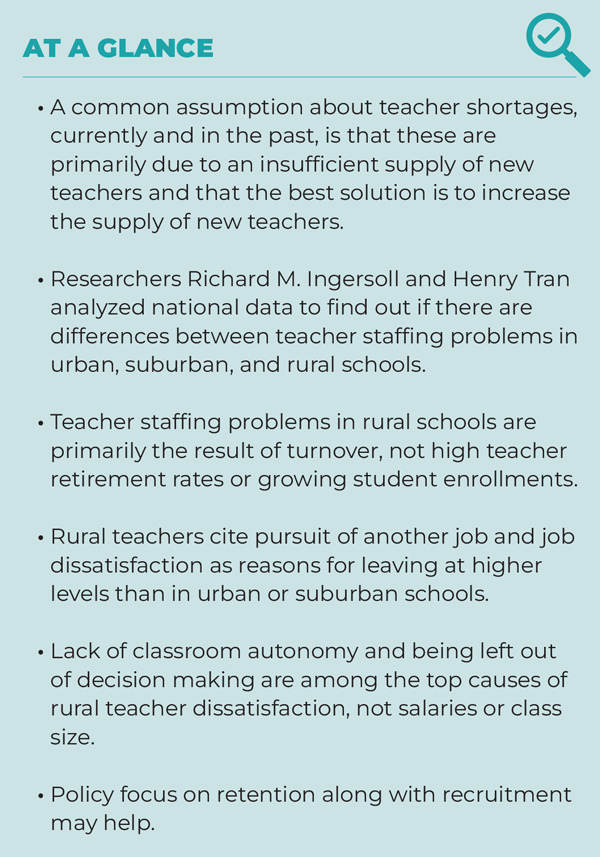

We began our analysis by examining demographic changes in rural education, including student enrollments and the size and age of the teaching force. The data show that, over the past two decades, the number of schools, students, and teachers in rural areas have decreased sharply. This is in contrast to urban and suburban communities. For example, while the teaching force in urban and suburban school systems both increased by about a fifth in that timeframe, it decreased by about a fifth in rural schools (see Figure 1). Moreover, unlike in urban and suburban schools during the past decade, the average age of the rural teaching force has decreased, resulting in a decrease in the number and percentage of teachers approaching retirement age.

Given these demographic changes in rural schools, traditional teacher shortage theory would predict that such schools should see demand for new teachers decrease. Thus, they should have less difficulty staffing their classrooms and suffer less from teacher shortages. In contrast, theory also would expect the opposite in urban and suburban schools — their increase in students, retirement-age teachers, and the number of teachers employed could lead to staffing problems. Do the data confirm this?

Rural schools suffer from serious teacher staffing problems

The most grounded and accurate measures of the extent of teacher staffing problems and teacher shortages in schools are data from school administrators on the actual degree of difficulty they encounter filling open teaching positions. These data show that over the past two decades, in any given year, most schools have had openings for teachers. A significant percentage of these schools have had difficulty filling their open positions.

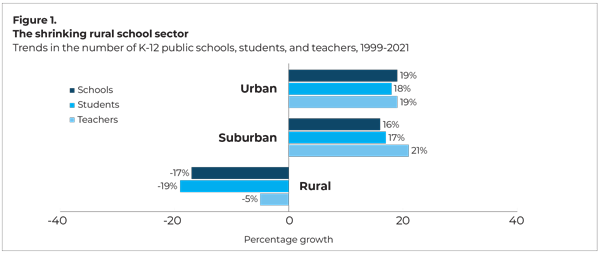

For instance, at the start of the 2020-21 school year, about 80% of public secondary schools, urban, suburban, and rural alike, had to recruit and interview teachers for open teaching positions in one or more of their key subjects. Among the rural schools, 59% had serious difficulty filling one or more of those openings — a percentage that was higher than in urban or suburban schools (Figure 2). The data also show large differences in vacancies and staffing difficulties for certain subject areas. The fields of mathematics, science, and special education have long experienced the most serious staffing problems.

In short, despite a decrease in the number of students and teachers, many rural schools have nevertheless suffered from difficulties staffing their teaching positions, even more so than urban and suburban schools.

Rural schools suffer from a revolving door of teachers

The above data from school administrators on the degree of difficulty filling openings is a useful empirical measure of teacher staffing problems. However, these data do not indicate the sources of these difficulties.

Our analyses show that the need for new hires in rural schools and the accompanying staffing difficulties are not driven by increases in student enrollments, because student enrollments in rural schools have decreased. Rather, the data show that the hiring of new teachers in rural schools each year largely serves to fill spots vacated by teachers who departed their schools at the end of the previous school year. Most of those departures are not due to teacher retirements. Our data indicate that pre-retirement teacher turnover is the primary driver of staffing problems in rural schools.

Teachers were over twice as likely to move out of rural schools and to urban or suburban schools as they were to move from urban or suburban schools to rural schools.

Researchers have long held that elementary and secondary schools suffer from high teacher turnover (Lortie, 1975; Tyack, 1974; Murnane et al., 1991). To put this in context, we analyzed national data from the NCES Baccalaureate and Beyond Survey, a longitudinal survey that followed college graduates for 10 years, to compare teacher attrition rates (those leaving the occupation entirely) to attrition rates for other lines of work. We found that attrition in teaching is, in fact, lower than in some professions, such as childcare workers, secretaries, and paralegals. It is slightly higher than for police officers and nurses and far higher than for many professions, such as lawyers, engineers, architects, physical therapists, and pharmacists. K-12 teachers form one of the largest occupational groups in the nation, so their relatively high departure rates means that, numerically, the flow of teachers in and out of schools is quite large.

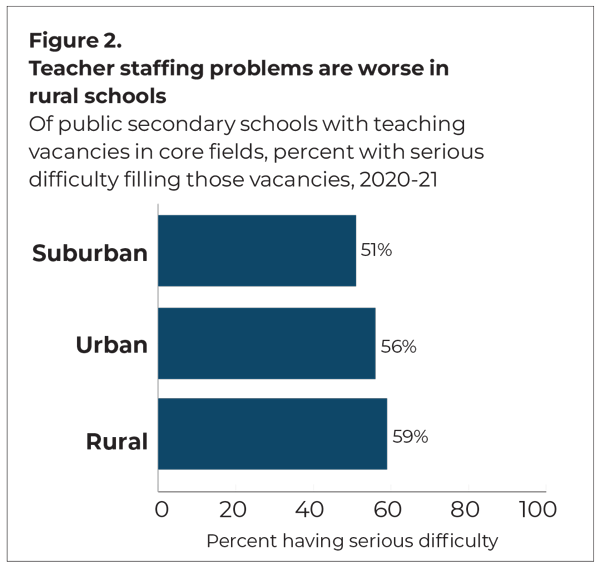

To try to capture the magnitude of the flow of teachers in and out of schools, we analyzed the national SASS and TFS data on both teacher hiring and turnover for 2013, the most recent data available. While these data are older, we have found these same patterns and proportions in other years. As shown in Figure 3, about 90,000 teachers entered rural public schools at the beginning of the school year. By the next school year, about 145,000 — equivalent to 162% of those just hired — departed from their schools, either to other schools or to other lines of work. Thus, during the 10 to 12 months before, during, and after that school year, there were about 245,000 teacher job transitions into, between, or out of rural public schools. This represents about one quarter of the entire rural public teaching force — a scenario reflecting a “revolving door” (Figure 3).

Total teacher turnover as depicted in Figure 3 is evenly split between its two major components: migration to other schools and attrition from teaching altogether. Teacher migration, of course, does not decrease the overall net supply of teachers and does not contribute to overall shortages. However, cross-school and cross-district moving usually does result in the need to replace staff. This means potential staffing difficulties and staffing problems. Moreover, as we show in the next section, teacher cross-school migration is asymmetric. The flows to and from schools in different locations are not evenly balanced.

Of course, not all teacher turnover is detrimental. Across a range of occupations and industries, job and career changes are normal and common. However, employee turnover can be costly for employers. And high levels of departures from an organization can be a symptom of underlying problems. Research has also shown this to be true for schools (Ingersoll & Tran, 2023). Our research has documented that one negative consequence of teacher turnover is its pivotal role in teacher shortages.

Rates of turnover differ between types of schools

The overall levels of turnover mask large differences in teacher departure rates across different settings. Teacher turnover is not spread evenly. In any given year, almost half of all public school teacher turnover takes place in just one quarter of public schools.

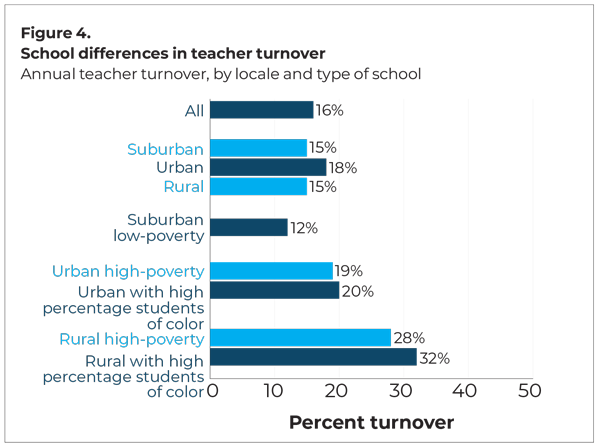

As shown in Figure 4, overall, there are not large differences in teacher turnover among rural, urban, and suburban schools. There are, however, large differences according to the demographic composition of the students and the community. Low-poverty suburban schools have the lowest levels of teacher turnover at 12% annually. On the other hand, urban schools with high levels of students of color or high levels of students from high-poverty communities have among the highest rates of turnover. Teacher turnover is even higher in high-poverty rural schools and rural schools with high levels of students of color. These rural schools face the most extreme teacher turnover of all schools, experiencing departures of between a quarter and a third of teachers annually (Figure 4).

Exacerbating the issue for rural schools are the large differences in the destinations of teachers who migrated from one school to another. Teachers were over twice as likely to move out of rural schools and to urban or suburban schools as they were to move from urban or suburban schools to rural schools. The result is an annual reshuffling of a large portion of the rural teaching force, with a net loss to rural schools and a net gain to urban and suburban schools.

Job dissatisfaction is the primary driver of rural teacher turnover

There are many reasons for teacher turnover. The TFS data show that teachers often indicate that their departures are due to retirement; school staffing actions (such as layoffs, terminations, school closings, and involuntary cross-school transfers); or family reasons (such as pregnancy, child rearing, health problems, and family moves). Another set of reasons involves teachers pursuing another job. Those include teachers who moved to another school because they felt it was a better teaching assignment and those who left teaching to pursue another career or to go back to school.

Notably, the most frequently cited set of reasons for leaving involves teachers’ dissatisfaction with various aspects of the teaching job. Forty-one percent of teachers departing from rural schools indicate they departed to pursue a different or better job, and 61% cite dissatisfaction as a main reason for their departures. Rural teachers cite pursuit of another job and job dissatisfaction as reasons for their departures at higher levels than in urban or suburban schools.

School working conditions are strongly linked to rural teacher turnover

There are many reasons behind the turnover of the 61% of teachers who departed rural schools because of dissatisfaction. Interestingly, though teacher salaries in rural school districts are, on average, lower than in urban or suburban school districts, dissatisfaction with salaries and benefits are among the least likely reasons given by rural teachers for their departures. Of those rural teachers who indicated that their departure was due to job dissatisfaction, only 34% reported that inadequate or poor salary and/or benefits were reasons for their departure. Also among the least likely reasons given by rural teachers is dissatisfaction with the numbers of students they taught (18%).

On the other hand, rural teachers departing because of dissatisfaction most frequently cited dissatisfaction with school administration (63%); accountability/testing (55%); and lack of classroom autonomy or input into decision making (50%) as sources of dissatisfaction.

The implications of our findings

While rural education has shrunk in size, rural schools continue to have more difficulty keeping their classrooms staffed than do urban and suburban schools, which have both seen increases in students and teachers. The shortages in rural schools are largely due to high levels of pre-retirement teacher turnover, especially in disadvantaged communities.

School management and leadership play a significant role in the solution to some teacher staffing problems. Many of the reasons for rural teacher turnover can be changed through policy, with implications for the leadership of schools.

Long-standing theory on teacher shortages holds that the main source of the problem is an insufficient supply of new teachers in the face of student enrollment and teacher retirement increases. In turn, efforts to increase the supply of new teachers have long been a dominant reform strategy. Nothing in this study suggests these efforts are not worthwhile. However, the data indicate that teacher recruitment strategies, alone, do not directly address a major root source of teacher staffing problems — pre-retirement turnover. In short, recruiting more teachers, while an important first step, will not fully solve school staffing inadequacies if large numbers of teachers then depart in a few years. Increasing retention could prevent the loss of such investments and lessen the ongoing need for new recruitment initiatives.

School management and leadership play a significant role in the solution to some teacher staffing problems. Many of the reasons for rural teacher turnover can be changed through policy, with implications for the leadership of schools. The finding that neither salary/benefits nor class-size reduction are the main reasons for teacher turnover in rural schools is important because, on a practical level, salary increases, and class-size reduction are relatively expensive. In contrast, major reasons for teacher turnover include school management issues, such classroom autonomy and ability to have input into schoolwide decisions.

Altering these organizational conditions would not necessarily be easy. There can be numerous financial, political, organizational, and legal barriers to making these improvements. However, changing some of these organizational conditions would be less costly financially than teacher salary increases and class-size reduction — an important consideration, especially in disadvantaged settings. Retaining teachers through changing conditions, especially in high-poverty rural schools, could prevent some turnover in the future, which will come at a higher cost than making these changes that may encourage teachers to stay.

Note: This article is drawn from a longer paper published in Educational Administration Quarterly (Ingersoll & Tran, 2023).

References

Ingersoll, R. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: An organizational analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 38 (3), 499-534.

Ingersoll, R. & Perda, D. (2010). Is the supply of mathematics and science teachers sufficient? American Educational Research Journal, 47 (3), 563-94.

Ingersoll, R., May, H., & Collins, G. (2019). Recruitment, employment, retention and the minority teacher shortage. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27, 37.

Ingersoll, R. & Tran, H. (2023). Teacher shortages and turnover in rural schools in the U.S.: An organizational analysis. Educational Administration Quarterly, 59 (2), 396-431.

Lortie, D. (1975). School teacher. University of Chicago Press.

Murnane, R., Singer, J., Willett, J., Kemple, J., & Olsen, R. (1991). Who will teach? Policies that matter. Harvard University Press.

Tieken, M.C. (2017). The spatialization of racial inequity and educational opportunity: Rethinking the rural/urban divide. Peabody Journal of Education, 92 (3), 385-404.

Tran, H. & Dou, J. (2019). An exploratory examination of what types of administrative support matter for rural teacher talent management: The rural educator perspective. Education Leadership Review, 20 (1), 133-149.

Tran, H., Hardie, S., Gause, S., Moyi, P., & Ylimaki, R. (2020). Leveraging the perspectives of rural educators to develop realistic job previews for rural teacher recruitment and retention. The Rural Educator, 41 (2), 31-46.

Tyack. D. (1974). The one best system. Harvard University Press.

This article appears in the November 2023 issue of Kappan, Vol. 105, No. 3, p. 36-41.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Richard M. Ingersoll

RICHARD M. INGERSOLL is a professor of education and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Henry Tran

HENRY TRAN is an associate professor in the Department of Educational Leadership and Policies at the University of South Carolina, Columbia.