During some of my most grueling days as a school principal — which sometimes started at 5 a.m. and didn’t end until after 9 p.m. — I would come home bone-tired from meetings, overwhelmed with student, staff, and parent concerns, drowning in unanswered emails, and feeling the weight of deadlines pressing on my chest like a bag of stones. On those days, I would collapse into bed with my phone, pull up a YouTube video of the poet Mary Oliver reciting “Wild Geese,” close my eyes, and listen to the poem again and again.

You do not have to be good, the poem begins. Every time, I felt as though Oliver herself had just absolved me for my failure to meet the principalship’s near-impossible demands. You do not have to walk on your knees / for a hundred miles through the desert repenting, she assured me. And subsequent lines stirred in me the belief that I could press on, that better days were on the horizon: Whoever you are, no matter how lonely / the world offers itself to your imagination / calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting–

I first read “Wild Geese” in my graduate-level Philosophy of Education class. On the last day of the semester, just before dismissing us, the professor asked if someone would be willing to read something aloud to the class. I broke the awkward silence — “I’ll do it.” She handed me a dog-eared copy of Dream Work, a collection of Oliver’s poems, and told me which one to recite. After I finished, the room stayed quiet; the poem swelled in the air between us, filling every inch of classroom space. Finally, she thanked all of us and wished us well on our ascension into educational leadership.

I didn’t understand poetry’s significance to my work until much later in my career, but now I know that a poetic practice is essential to effective change leadership.

Poetic leadership

Today, as a principal supervisor, I am responsible for coaching and supporting leaders through one of the most arduous periods in the history of American education. Over the past year, principals have had to keep hundreds of students physically and emotionally safe during a global pandemic, even while participating in a national reckoning with racial injustice. I’ve seen principals tear up in anguish over how to heal their school community, how to emerge stronger than we were before the pandemic, how to avoid reverting to the status quo, and how to create a more humane, just, and student-centered school community. The principals I work with have made a commitment to critical pedagogy, which requires them to ask hard questions about the way the school day is structured, whose voices and stories are represented in the curriculum, who plays a role in decision making, and how their schools uphold or subvert dominant educational myths. Without a sense of hope that things can, in fact, be different, the toughest principals can grow weary when doing this work. My job as a principal coach is to make sure the leaders in my care don’t become jaded.

I often find myself thinking about poetry and what it did for me as a principal, and also about Maxine Greene’s (1986) argument that we can use poetry to spur change:

Poets move us to give play to our imaginations, to enlarge the scope of lived experience and reach beyond from our own grounds. Poets do not give us answers; they do not solve the problems of critical pedagogy. They can, however, if we will them to do so, awaken us to reflectiveness, to a recovery of lost landscapes and lost spontaneities. (p. 428)

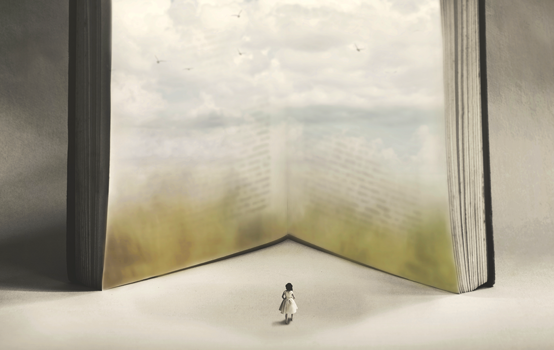

As Greene says, poetry can provide the vision we need to make the leap between our present state and what feels impossible. Poems behave like portals; they show us new and different perspectives and in turn help us gain empathy for others. Reading poetry requires us to grapple with questions about what it means to be human — to feel love, grief, joy, despair, shame, and renewal. Poetic experiences enrich our inner lives, making us more self-aware, compassionate, and open-minded.

Poetry also often helps us express our feelings at significant moments in history. Amanda Gorman, America’s first National Youth Poet Laureate, delivered her poem, “The Hill We Climb,” at President Joe Biden’s inauguration to overwhelming bipartisan acclaim. Gorman’s poem was both a literal and figurative convocation — a counterstatement to Trumpism that illustrated the pain and suffering caused by racism, sexism, and the pandemic, while at the same time inciting hope:

The new dawn blooms as we free it.

For there is always light,

if only we’re brave enough to see it,

If only we’re brave enough to be it.

Since Gorman’s remarkable performance, I have seen poetry appear more frequently in unexpected places. At a recent professional development on curriculum integration, the presenter ended his session with a 2018 video clip of Gorman reciting a poem. Gorman has struck a chord with us and hopefully inspired a new commitment to poetry.

Mary Oliver, too, continues to inspire me. Poet Hayden Carruth described Oliver’s Dream Work collection as “a spirited, expressive meditation on the impossibilities of what we call lives, and on the gratifications of change.” Principals who meditate on the possibilities in education and the satisfaction of disrupting a pernicious system are doing their own courageous and creative dream work.

For instance, determining how to use the historic amount of federal education dollars soon to be infused into schools is an exercise in dream work. Do principals dare to dream of healing their schools through arts programs? Dare they dream to abolish harmful sorting and ranking mechanisms? Dare they dream of making their students’ communities their classrooms? Dare they, as Gorman would have it, step out of the shade, aflame and unafraid?

The power of dreams

This creative work, this dream work, may sound romantic, but it is not foolish. The harsh reality is that while the pandemic has presented educators with an opportunity to rethink our teaching strategies, institutional forces are at work to preserve existing structures. In their book, Imagination First: Unlocking the Power of Possibility, Eric Liu and Scott Noppe-Brandon (2009) attribute a lack of imagination to “path dependence,” the tendency for organizations to continue to institute practices out of habit, despite the evidence that these solutions are minimally effective. Dream work, then, is the ability to carve a new path by “rekindling a youthful naivete, a willful bewilderment” about the inadequacy we often tolerate in schools (p. 211). Fear-based narratives that focus on “learning loss” have been effective at keeping things like high-stakes testing, summer school remediation, and rote instruction intact both pre-COVID and now, as the pandemic appears to be ebbing.

School leaders must resist the rhetoric of fear and do the dream work of critical pedagogy, remaining ever vigilant to ensure that their quotidian job responsibilities and fear of declining test scores do not crowd out or stifle the changes we can and must make to our system. Leveraging the power of poetry is one way to inspire hope. Whether by reading and discussing a poem together before diving into a brainstorming session, or coming to a work session with a poem that inspires them, principals need to make space for harnessing the poetic imagination.

In fall 2020, I brought all of my leaders together to share a goal they were passionate about implementing in their schools. We didn’t talk about fear or test scores or COVID slide. Instead, we talked about hope. The leaders jumped in and offered up resources and encouragement to one another. We committed to our goals in this public forum and decided we would use the group as an accountability system. Throughout the school year, we’ve continued to meet biweekly and share our progress.

Until recently, my own poetic practice had remained private and personal. But this year I was moved to share poetry’s effect on me. One of the leaders I coach had written a heartfelt meditation on the pressure he has felt throughout his life to be perfect, and how heavy it feels when perfection eludes him (all of us) in leadership. I took this moment as an opportunity to share my own story of feeling overwhelmed as a principal, how I turned to poetry for refuge, and gave him a copy of Oliver’s poem to hang in his office as a reminder to go easy on himself — but also to keep reaching for more.

Though I’ve only just recently attempted to incorporate the power of poetry into my conversations, I aspire to incorporate it more regularly into my leadership coaching. I am especially looking forward to using poetry in a rising leaders academy that my colleagues and I are coordinating for the 2021-22 school year.

Like good poetry, an exhilarating personal goal can both console us and compel us to change — it can “awaken us to reflectiveness, to a recovery of lost landscapes and lost spontaneities,” as Greene (1986) says. This year, it feels especially urgent for leaders to evoke the power of poetry to imagine the possibilities on the other side of this global pandemic. During our most difficult days, when fear bears down and we are tempted to settle for more of the same instead of fighting for something new, we must make time for the dream work, time to listen to what stirs hope inside of us, what calls to us over and over, urging us to make dreams into reality.

References

Gorman, A. (2021). The hill we climb. In The hill we climb and other poems. Penguin Random House.

Greene, M. (1986). In search of a critical pedagogy. Harvard Educational Review, 56 (4), 427-442.

Liu, E. & Noppe-Brandon, S. (2009). Imagination first: Unlocking the power of possibility. Jossey-Bass.

Oliver, M. (1986). Dream work. Atlantic Monthly Press.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sarah Pazur

SARAH PAZUR is the director of school leadership for a network of public school academies in Michigan and the cofounder of FlexTech Education.