COVID-19 changed how states use standardized tests. What might that mean for the future?

Americans have long debated the value of standardized testing requirements in K-12 education, such as those instituted under No Child Left Behind (NCLB) and continued under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). While research has shown that students’ performance on such tests tends to be predictive of their later outcomes in school (Goldhaber & Özek, 2019), arguments rage on as to whether testing can lead to improvements in students’ outcomes and, if so, whether the benefits outweigh the costs of administering them. For instance, critics have argued that test results rarely provide actionable and timely information about individual students’ skills or needs (Marsh, Pane, & Hamilton, 2006) and that test-based accountability leads teachers and schools to spend excessive time on test preparation and focus on a narrow band of tested subjects (e.g., Koretz, 2009, 2017).

Recent reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic offer some insight into state and federal officials’ current thinking about the usefulness of such tests and their overall costs and benefits. In the 2019-20 school year, as school buildings closed, all ESSA-required tests were canceled, prompting questions as to whether they ought to be required in 2020-21. Ultimately, the U.S. Department of Education (USDOE) allowed for some testing flexibility in the form of ESSA waivers. In turn, states’ waiver requests provide some clues as to how policy makers think those tests should be used in the future.

The uses of standardized tests

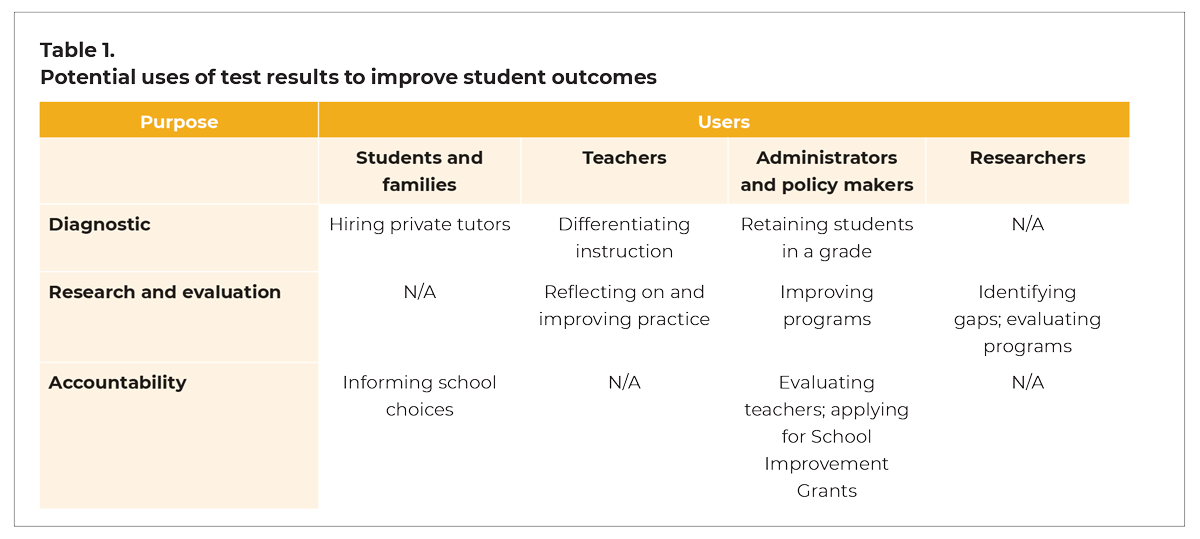

Beliefs about how testing can improve education typically fall into at least one of three categories. First, tests can be treated as diagnostic tools, used to determine how to target educational supports. For example, they might be used at the student level to make decisions about holding children back a grade, offering them extra tutoring, or giving them advanced coursework (e.g., Figlio & Özek, 2020; McEachin, Domina, & Penner, 2020). Similarly, test results can be used to diagnose schoolwide needs, as with NCLB’s requirement that School Improvement Funds and technical assistance be directed to schools based on their test scores (McClure, 2005). Second, test results can be useful for research and evaluation. For example, test scores are widely used to assess the effectiveness of educational interventions, practices, and policies, or to measure achievement gaps between groups of students. Third, under both NCLB and ESSA, tests are a prominent part of school accountability systems (O’Keefe, Rotherham, & O’Neal Schiess, 2021). Here, the idea is that rewards or sanctions connected to test results can drive teachers and schools to improve their practices (e.g., Dee & Jacob, 2011; Reback, Rockoff, & Schwartz, 2014; Wong, Cook, & Steiner, 2015).

These three ways of using test results are not mutually exclusive, but they are based on different theories of action about how testing can lead to improved student outcomes. And, relatedly, these theories of action vary depending on who is expected to use the test results. (Table 1 lists some of the most common combinations of purpose and user imagined by testing advocates.)

For years, a majority of the American public has supported federal testing requirements (Henderson et al., 2019). However, this support appears to be fragile and declining. For example, 41% of respondents to the 2020 PDK poll endorsed the view that there is “too much emphasis on achievement testing” in public schools, up from 37% in 2008 and 20% in 1997 (PDK International, 2020). And when survey-takers are given more information about the ways in which tests are actually administered and the scores are used, support declines still further — for instance, a recent study found that when people are told that test administration consumes an average of eight instructional hours per year, net support for testing requirements falls by 20 percentage points (Henderson et al., 2019).

The question is not only whether the pandemic will change how state tests are used, but also whether that will, in turn, have implications for how testing is viewed by the public and the viability of testing policy going forward. And for recent evidence of policy makers’ thinking about the uses of standardized tests, we can look to their requests to waive specific testing requirements for the 2020-21 school year.

ESSA test waivers in 2021

Given the challenges of administering tests during the pandemic, when large numbers of students were learning remotely, the U.S. Department of Education (USDOE) allowed states to request waivers from some ESSA testing requirements for the 2020-21 school year. Specifically, on Feb. 22, 2021, USDOE released formal guidance explaining how states could request temporary ESSA flexibility in three areas (Rosenblum, 2021): They could ask to waive accountability and school identification requirements (such as the use of test data to differentiate schools); they could ask to waive some public reporting requirements (especially those related to test scores); and they could request flexibility in test administration (allowing them to administer tests remotely, for example, or to lengthen testing windows, making it easier for schools to keep students physically distanced for tests).

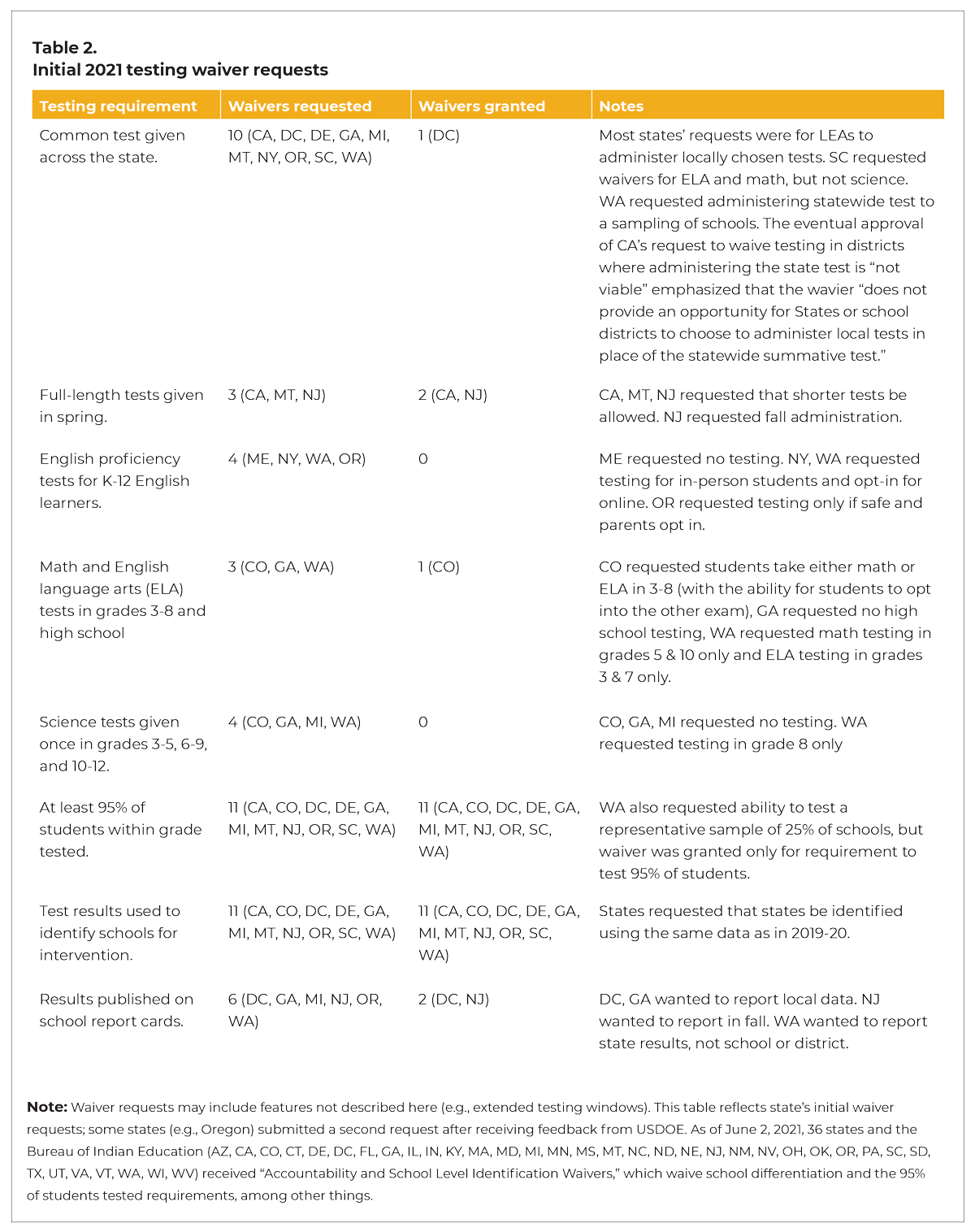

Relatively few states chose to take advantage of these options. Indeed, while USDOE guaranteed requesting states they would waive requirements that 95% of students participate in testing and that test results be used to differentiate schools, just 36 states requested such waivers. Moreover, just 12 states (see Table 2) requested waivers that went beyond those minimal requests. Given that we don’t know what sorts of political negotiations went on behind the scenes — whether among local officials or between states and the USDOE — it’s impossible to say precisely why so many states chose not to request more waivers (though this does leave the impression that many policy makers continue to assign high value to annual testing and have little interest in changing the status quo).

But what might we learn from the 12 states that did request additional waivers? As it turns out, their requests bore some striking similarities, suggesting a shared sense of priorities for the future of testing policy:

Flexibility wins out over comparability

Several of the 12 states requested changes (many of which the USDOE approved) that allow local districts to make their own decisions about the timing and length of tests, the grades and subjects tested, and even the testing instruments they use. In short, they requested that districts be given more flexibility to use tests in ways that best meet their needs, even if this means that it will become difficult to compare students’ and schools’ performance from one district to another, or from one year to the next (Kuhfeld, Domina, & Hanselman, 2019).

When it comes to using tests for purposes of school accountability, this doesn’t necessarily pose a problem. Though researchers tend to prefer growth-based measures of school performance (Polikoff, 2017), most states determine school quality based on a single set of end-of-year test scores, rather than by assessing students’ progress over multiple years — that is, their accountability systems don’t require scores to be comparable over time, so they don’t need tests to be consistent from one year to the next.

But when it comes to educational research, it does create serious problems to give districts so much flexibility. For instance, if a district decides to introduce new tests or testing protocols every few years, then how can researchers analyze long-term trends in student performance? Further, even where common tests are administered statewide, other areas of flexibility may make results difficult to compare across jurisdictions or years. In particular, waiving the requirement that 95% of eligible students participate in testing could have a massive effect on student subgroups, particularly those whose numbers are already small (where losing a few students could significantly change the makeup of the group). If the students being assessed vary by large percentages from year to year, comparisons across years and between groups become less reliable. As a result, uncertainty about student achievement, including how it was affected by the pandemic, is likely to echo across education research, policy, and practice for years.

Even less useful feedback from states

It has always been difficult to use state test results for diagnostic purposes (such as to determine which students need remediation), given the lag between when tests are taken and when schools receive results. But where states have delayed their testing, as USDOE encouraged, using the results diagnostically will be especially difficult. In one extreme case, New Jersey received approval to move its state test into the fall, which makes it impossible for districts to use the results to inform summer programming, or for families to use them to select summer programs for their children. Even before the pandemic, states gave parents very little information about their children’s growth on such tests — they rarely said much more than whether their kids were performing below, at, or above state standards (Goodman & Hambelton, 2004). However, these waivers will make it even more challenging to get detailed, actionable, and timely information to parents.

A hard line on common assessments

According to our analysis, excluding proposals to waive the administration of common statewide tests, 70% of states’ waiver requests were approved by President Joe Biden’s administration. However, while many states requested permission to use assessments selected by local education agencies (LEAs), only the District of Columbia (where most LEAs are charter school networks) was able to secure such a waiver. But why would the federal government draw a particularly hard line here, while granting considerable flexibility in other areas (such as the timing and percentage of students tested)? We can only speculate, but it strikes us that federal policy makers may have been leery of agreeing to even a temporary waiver of statewide tests in 2021, since a second year without tests (after tests were canceled in 2020) might seem to suggest a permanent policy change, giving momentum to efforts to eliminate testing altogether.

General implications for testing policy

The fact that such a small share of states applied for additional waivers shows that there is still a lot of state-level support for standardized testing — or at least a state-level belief that testing is here to stay. But still, there are lessons to be learned from the waivers that states did seek.

Policy makers and testing advocates should be more careful to articulate a specific theory of action about who will be using the test results for what purposes.

First, the waiver requests that we reviewed — as well as the public opinion polls discussed above — suggest that in some states, officials have serious doubts about the usefulness of annual testing. We suggest, then, that policy makers and testing advocates should be more careful to articulate a specific theory of action about who will be using the test results for what purposes (as depicted in Table 1). Often, supporters of testing respond to criticism simply by insisting that tests are indispensable — for instance, they often make the vague assertion that “we cannot fix what we do not measure.” But while that may be an effective sound bite, it doesn’t provide much of a rationale for any specific aspect of a testing program. Testing, in and of itself, is not useful; a testing program should be designed with specific uses in mind. For example, if a purpose of testing is to help leaders or researchers evaluate the effectiveness of a program, having consistent statewide data from before, during, and after the program implementation is essential, and allowing localities to choose their own assessments would limit the ability of tests to accomplish this goal. On the other hand, a testing program intended to diagnose how teachers should differentiate instruction for individual students might be stymied by a testing program that is slow to share student-level results.

Second, we have a warning for those who — like us — believe that standardized tests can play a useful role in improving educational outcomes: Maintaining political support for such tests — and especially for statewide standardized tests — probably depends on demonstrating their diagnostic value, as the public tends to favor this use of testing (PDK International, 2020). By contrast, testing for accountability is controversial, and the use of tests to support research and evaluation doesn’t inspire much support from the general public. Most parents and educators do understand and support diagnostic uses of testing, though. Such testing provides concrete and immediate benefits to students and schools, benefits that have often been neglected even by staunch advocates of standardized testing. This is evidenced in part by how poorly state testing policy is typically designed for diagnostic purposes. Even prior to the pandemic, state test results have often taken too long to receive and provided too little accessible and useful information about what individual students need (Goodman & Hambleton, 2004; Marsh, Pane, & Hamilton, 2006; Mulvenon, Stegman, & Ritter, 2005). It is, therefore, no surprise that many might resist subjecting students to the stress of tests during already tumultuous times.

Sketching out a comprehensive plan for diagnostic state tests is beyond the scope of this article, but English language proficiency (ELP) testing may provide some useful lessons. As shown in Table 2, only four states requested waivers from ELP requirements, and these were minor, which may suggest that this sort of statewide standardized testing has few opponents. Why? Perhaps because it is more diagnostically useful than other tests. In our experience, stakeholders generally believe that ELP results are at least somewhat credible signals of important student skills and can be used to determine which students need specific services. In other words, because it provides timely, credible information that educators are able to use, few states saw a reason to waive this testing requirement.

The COVID-19 pandemic has given states the opportunity to abandon certain testing requirements, even as it has heightened concerns that many students need substantial interventions to address lost learning opportunities. We encourage policy makers to think more carefully, explicitly, and publicly about how their standardized testing policies achieve various diagnostic, research, and accountability objectives and ensure that the requirements that remain in place after the pandemic will actually allow tests to achieve those goals. This will bolster fragile political support for statewide tests and, more important, will help to ensure that standardized tests have benefits for more schools and students.

References

Dee, T. S. & Jacob, B.A. (2011). The impact of No Child Left Behind on student achievement. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 30 (3), 418-446.

Fazlul, I., Koedel, C., Parsons, E., & Qian, C. (2021). Estimating test-score growth with a gap year in the data. (Working Paper No. 248-0121). Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER).

Fensterwald, J. (2021, May 3). California state board likely to adopt long-awaited ‘student growth model’ to measure test scores. EdSource.

Figlio, D. & Özek, U. (2020). An extra year to learn English? Early grade retention and the human capital development of English learners. Journal of Public Economics, 186, 104-184.

Goldhaber, D. & Özek, U. (2019). How much should we rely on student test achievement as a measure of success? Educational Researcher, 48 (7), 479-483.

Goodman, D.P. & Hambleton, R.K. (2004). Student test score reports and interpretive guides: Review of current practices and suggestions for future research. Applied Measurement in Education, 17 (2), 145-220.

Henderson, M.B., Houston, D., Peterson, P.E., & West, M.R. (2019, August 20). Public support grows for higher teacher pay and expanded school choice: Results from the 2019 Education Next poll. Education Next.

Koretz, D. (2009). Measuring up: What educational testing really tells us. Harvard University Press.

Koretz, D. (2017). The testing charade: Pretending to make schools better. University of Chicago Press.

Kuhfeld, M., Domina, T., & Hanselman, P. (2019). Validating the SEDA measures of district educational opportunities via a common assessment. AERA Open, 5 (2).

Marsh, J.A., Pane, J.F., & Hamilton, L.S. (2006). Making sense of data-driven decision making in education: Evidence from recent RAND research (OP-170-EDU). RAND Corporation.

McClure, P. (2005). School improvement under No Child Left Behind. Center for American Progress.

McEachin, A., Domina, T., & Penner, A. (2020). Heterogeneous effects of early algebra across California middle schools. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 39 (3), 772-800.

Mulvenon, S.W., Stegman, C.E., & Ritter, G. (2005). Test anxiety: A multifaceted study on the perceptions of teachers, principals, counselors, students, and parents. International Journal of Testing, 5 (1), 37-61.

O’Keefe, B., Rotherham, A., & O’Neal Schiess, J. (2021). Reshaping test and accountability in 2021 and beyond. State Education Standard, 21 (2), 7-12.

PDK International. (2020). Public school priorities in a political year: 52nd Annual PDK Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward the Public Schools. Author.

Polikoff, M. (2017, March 20). Proficiency vs. growth: Toward a better measure. FutureEd.

Reback, R., Rockoff, J., & Schwartz, H.L. (2014). Under pressure: Job security, resource allocation, and productivity in schools under No Child Left Behind. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6 (3), 207-241.

Rosenblum, I. (2021, February 22). Letter to chief state school officers. U.S. Department of Education. www2.ed.gov/policy/elsec/guid/stateletters/dcl-tests-and-acct-022221.pdf

Wong, M., Cook, T.D., & Steiner, P.M. (2015). Adding design elements to improve time series designs: No Child Left Behind as an example of causal pattern-matching. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 8 (2), 245-279.

This article appears in the November 2021 issue of Kappan, Vol. 103, No. 3, pp. 48-53.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dan Goldhaber

DAN GOLDHABER is director of the Center for Education Data and Research at the University of Washington and the director of the National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research at the American Institutes for Research , Seattle, WA.

Paul Bruno

PAUL BRUNO is an assistant professor of education policy, organization, and leadership at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.