Vaccination laws require courts to balance individual rights and beliefs with the good of the public as a whole.

In 2000, public health officials declared that measles had been eradicated as a public health risk in the United States. Recently, however, measles infections have spiked around the world, including in the U.S. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2020), more than 1,000 cases of measles were reported across 31 states in 2019. This is the highest rate of measles in the U.S. since 1992. Compare this with 667 cases of measles reported in 2014, the highest rate in the past decade, and 55 in 2012, the lowest rate.

Immunizations protect individuals and the larger population, but age and certain medical conditions prevent some people from being able to be vaccinated safely. When immunization rates are high, community or herd immunity develops, protecting not only those who are immunized, but also those who cannot receive vaccines. However, when immunization rates are low, disease outbreaks may occur, creating a health hazard and putting those who cannot be immunized at risk.

Vaccination requirements were put in place in the early part of the 20th century as a way to address the spread of smallpox. Since then, state and local policy makers have implemented vaccination requirements to limit disease outbreaks and improve herd immunity in their communities. But some people consider it government overreach when authorities intervene in parents’ decision making about their children’s health care in this way. Some families have religious beliefs that prohibit medical intervention, including vaccination, or the introduction of foreign substances into the body. And some believe vaccines don’t help or that they can in fact make their kids sick or cause certain disorders. (The belief in a link between vaccines and autism spectrum disorder persists even though the peer-reviewed medical literature has debunked this claim; Taylor, Swerdferger, & Eslick, 2014). In response to these concerns, in the last part of the 20th century, many states reduced their vaccination requirements or began allowing more exemptions.

States have the authority to require vaccinations

It has long been clear that state and local governments, as part of their authority to regulate for the general welfare of their residents, can require vaccinations. More than a century ago, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a local government vaccination requirement in Jacobson v. Massachusetts (U.S. 1905). In this case, the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts, required the vaccination of all residents to combat the spread of smallpox. An exemption was made for those who could not be vaccinated for medical reasons. Jacobson refused vaccination, was fined, and challenged the city’s requirement. In spite of the argument that the state had no authority to require an individual to be subjected to this medical treatment, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the city’s authority to require vaccinations for the common good:

There are . . . restraints to which every person is necessarily subject for the common good. . . . Society based on the rule that each one is a law unto himself would soon be confronted with disorder and anarchy. Real liberty for all could not exist under the operation of a principle which recognizes the right of each individual person to use his own, whether in respect of his person or his property, regardless of the injury that may be done to others. [I]t was the duty of the constituted authorities primarily to keep in view the welfare, comfort and safety of the many, and not permit the interests of the many to be subordinated to the wishes or convenience of the few.

Although the Supreme Court has not ruled on vaccination requirements as a precondition for school enrollment or attendance, many other courts have upheld this requirement. In the first such reported case, Duffield v. School District of Williamsport (Pa. 1894), the Pennsylvania Supreme Court upheld a school board’s requirement that children be vaccinated for smallpox before they were enrolled in the district. The court found that the school board had the authority to require the vaccination as a way to “preserve the public health.”

It has long been clear that state and local governments, as part of their authority to regulate for the general welfare of their residents, can require vaccinations.

Current state requirements and exemptions

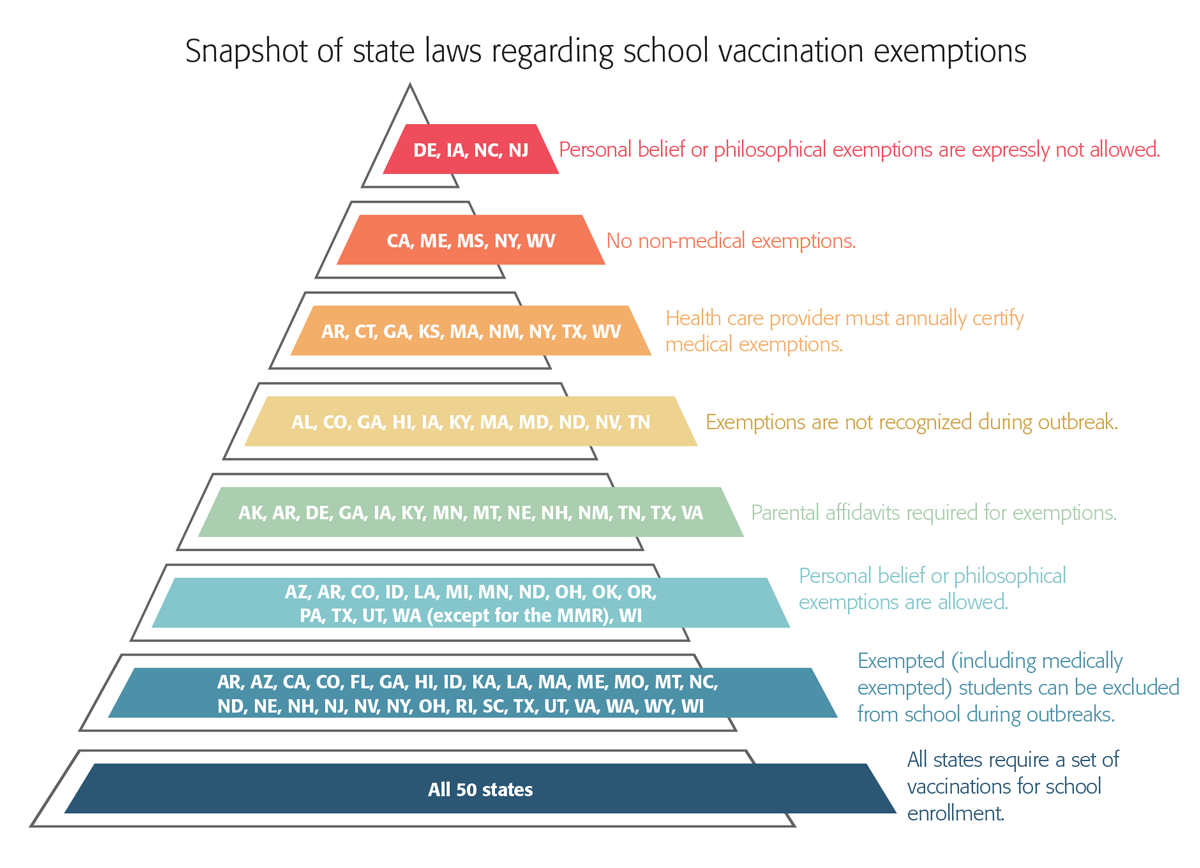

All states require students to have certain shots before enrolling in school to curb the spread of diseases. These requirements generally apply to all public, private, and preschool providers. They also grant exemptions to children for medical reasons, such as a weak immune system, although the specific exemptions vary from state to state. Additionally, 46 states allow exemptions on religious grounds, and 16 states allow parents to refuse vaccinations for their children for personal beliefs or philosophical reasons (CDC, 2017).

Because of a decline in vaccination rates and the subsequent outbreaks of measles, the most recent legislative trend has been for states to increase or tighten their school vaccination requirements. In 2015, Vermont removed its personal belief exemptions, and California removed both the personal belief and religious exemption. In 2019, Washington and Maine removed their personal belief exemptions, and New York removed its religious exemption (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2020).

Challenges to increased vaccination requirements

The four states — California, New York, Mississippi, West Virginia — with the most stringent vaccination requirements in the nation provide only for medical exemptions. The California and New York legislatures amended their statutes relatively recently, both in response to measles outbreaks in their states. Litigation challenging these stringent state statutes, alleging the right to personal belief and religious exemptions based on a variety of legal theories, has not been successful.

In Workman v. Mingo County (4th Cir. 2011), the federal Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld West Virginia’s law compelling vaccinations without a religious exemption. The parent in the case alleged that this violated her right to Free Exercise of Religion. The court found that it did not, citing a string of earlier cases that had ruled in favor of vaccinations over religious claims and a comment about vaccinations from the Supreme Court in a case about child labor (Prince v. Massachusetts, U.S. 1944). The Supreme Court there stated that the state’s “authority is not nullified merely because the parent grounds his claim to control the child’s course of conduct on religion or conscience. Thus, he cannot claim freedom from compulsory vaccination for the children more than for himself on religious grounds.”

F.F. v. State of New York (Sup. Ct. NY Albany County 2019) raises the issue of whether the repeal of the religious exemption from New York’s mandatory vaccination requirement violates people’s religious rights or discriminates against religious groups who reject vaccinations. The families argued that the legislature acted with hostility toward religion in repealing the exemption. The court found that there was no religious discrimination and that the state was acting to promote the public health in response to an increase in the spread of measles. Further, the court found that “Protecting public health, and children’s health in particular through attainment of threshold inoculation levels for community immunity from communicable diseases is unquestionably a compelling state interest.”

Similarly, the California courts have upheld the recent amendments to their vaccination requirements, which repealed the religious and personal belief exemptions after a measles outbreak in the state. In Love v. State Department of Education (Cal App. 3rd 2018), parents challenged this repeal, arguing that their right to direct the upbringing of their children, their privacy rights, and their children’s state right to education were violated. In Brown v. Smith (Cal. App. 2nd 2018), the parents alleged a violation of Free Exercise of Religion, Equal Protection, and their children’s state right to education. The courts found no merit in any of the parents’ allegations, repeatedly pointing to the depth of earlier court decisions finding that the state has a compelling state interest in protecting the health of the public through mandatory vaccinations. None of the constitutional allegations was found to rise to a level that would override that state interest.

Competing rights and the general welfare of all

Mandatory vaccination of children is a tough policy decision for legislatures because it involves competing rights and values and deciding whether the government or parents have the final say. But the science of vaccinations is clear: The greater the number of individuals who are immunized, the fewer the number of cases of the disease. When the vaccination rate is high enough, even those who are not medically able to be vaccinated are protected. When asked, the courts have consistently ruled in favor of protecting the general welfare of all.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). State school immunization requirements and vaccine exemption laws. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office for State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Support.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Measles cases and outbreaks. Atlanta, GA: Author. www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2020). States with religious and philosophical exemptions from school immunization requirements. Washington, DC: Author.

Taylor, L.E., Swerdferger, A.L., & Eslick, G.D. (2014). Vaccines are not associated with autism: An evidence-based meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies. Vaccine, 32 (29), 3623-3629

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Julie Underwood

Julie Underwood is the Susan Engeleiter Professor of Education Law, Policy, and Practice at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.