The Washington Post national education reporter describes how she wrote her new book about her hometown’s efforts to integrate schools — and why she’s opposed to engaging in media criticism.

By Alexander Russo

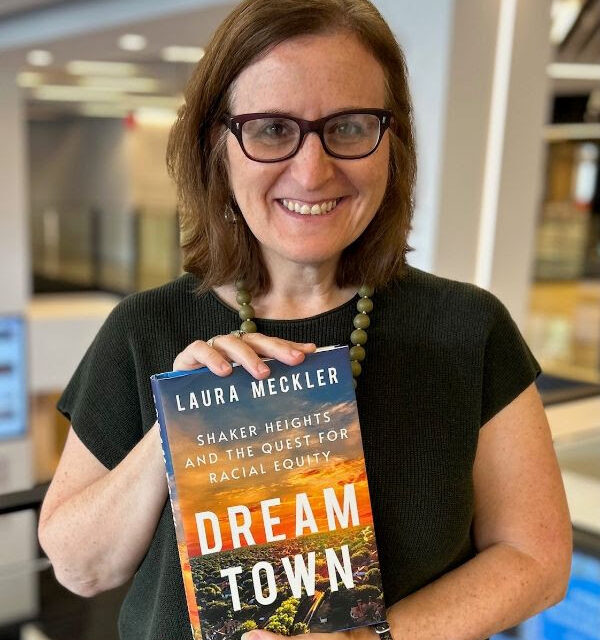

Washington Post reporter Laura Meckler is one of the most independent-minded reporters on the education beat.

She was among the first reporters to address the questionable effectiveness of closing schools and the early evidence that reopening could be done safely.

And now, with this week’s publication of “Dream Town,” the national education reporter is also a first-time author.

Her new book about integration efforts in Shaker Heights, Ohio, has already been featured on Fresh Air, excerpted in the Post, reviewed in the Cleveland Plain Dealer and Minneapolis Star Tribune, and covered in the Akron Beacon Journal and Cleveland Signal.

As you’ll see from the following interview, Meckler isn’t much interested in “Monday-morning quarterbacking” historic coverage of Shaker Heights’ integration efforts.

But she does share interesting thoughts on This American Life’s blockbuster “Nice White Parents” podcast and on the value in covering school culture wars.

And there’s lots to be learned from her descriptions of writing a book about her hometown school district, deepening her understanding of parents’ views on de-tracking and other equity-minded reform efforts, and the education topics that most warrant coverage in the new school year.

The following interview has been edited and condensed.

Above: The author and her new book

For folks who haven’t yet read it, how do you describe what “Dream Town” is all about?

LM: “Dream Town” is a book about my hometown of Shaker Heights and its long-term relationship with issues of race. It’s the story of a community that starts out as an elite refuge for wealthy Clevelanders but evolves into a pioneer of housing and school integration, and then, in more recent years, struggles with questions of true racial equity.

What was the motivation to write this, your first book?

LM: I did not go looking for a book to write. I was not pining to write a book and casting about for a subject. But when I came to the Washington Post and talked to my new editor about this story about Shaker Heights, he almost immediately said, “That could be a book.”

And then when I finished reporting and writing my story about Shaker for the paper in November 2019, I found that I didn’t want to be done with the topic. I realized that there was a fascinating story to tell and thought I was well positioned to tell it. I started talking to colleagues who had written books and to book agents, and the more I talked about this, the more excited I got.

Then, when the pandemic hit in March 2020, I thought, “If not now, when?” And I got serious about it.

The book reminds me of This American Life’s “Nice White Parents” podcast or the documentary TV series “America To Me.” Where does the book fit in for you?

LM: Those are great comparisons. One difference between those efforts and this book is I take a long sweep of history — starting with the founding of Shaker Heights at the turn of the 20th century. To me, that context helps understand what is happening today.

As for other comparisons, in addition to the titles you mentioned I’d point to “Little Fires Everywhere,” a fictionalized story set in Shaker Heights that a lot of people read or watched once it was made into a TV series. Of course, my version is non-fiction!

There also has been a fair bit of academic work, like a book called “Despite the Best Intentions,” which is about a school district in Illinois that looks at some of the same questions.

I’d point to “Little Fires Everywhere,” a fictionalized story set in Shaker Heights that a lot of people read or watched once it was made into a TV series.

How much media coverage did you find and use for the book — and what insights or observations would you make about the quality of the coverage you found?

LM: There has been a ton of newspaper coverage of Shaker. The New York Times alone has done about a dozen stories that are solely or primarily about Shaker Heights since 1963 which is pretty remarkable. But in terms of my research, the most valuable sources were local. I relied on coverage in particular from the Black press and the suburban newspaper that really covered Shaker Heights closely for many years. I would also give a shout-out to the high school newspaper, which has served an important role over the years and even more so today, with the scarcity of local news coverage.

As for the quality of the coverage, I’m not going to Monday-morning quarterback other people’s coverage of what they did in the moment. There were lots of times I thought, “This is this is so short. I want to know more about what happened here.” But there has been a real effort to write about Shaker and race over the years. Sure, with the benefit of time, we can all look back and say, “Well, maybe you missed this piece, or you missed that piece,” but I’m not going do that. I am grateful for what we have in terms of the historic record.

I’m not going to Monday-morning quarterback other people’s coverage… I am grateful for what we have.

Part of what you were doing with this book was going back and re-reporting your own reporting —

LM: I would say building on it. I wouldn’t necessarily say re-reporting it.

Ok, building on. Was there anything that you learned that was new or different from what you found in 2019?

LM: I think the 2019 story holds up very well. I don’t think there’s anything that is substantively different. I think that I just go much deeper. The story was centered on a particular controversy around a teacher and a Black student in her AP English class. I was able to tell a much fuller story — learning more about how and why things unfolded as they did, and frankly including more of what I already knew but didn’t have space for even in what was by any measure a long newspaper story.

So it just goes a lot deeper into those events, but I don’t think it’s inconsistent with what was reported in 2019. It just makes you realize how normally what we do every day just really scratches the surface. Beyond that particular element, with the book I was able to put all of this into the sweep of history and also to report deeply on other equity struggles the district has confronted, including some that unfolded as I was reporting the book.

What we do every day just really scratches the surface.

Looking at the overall book reporting process, did you experience any major (perspective-altering) surprises about the Shaker story or the focus on school integration?

LM: The thing that surprised me the most was how far back the Shaker schools’ tracking or levels system has been criticized as racially biased. I had been vaguely aware of some critiques in the early 1980s. In fact, there was a major Urban League report in 1980 that went after leveling in a comprehensive way. Parent groups had expressed concerns even before that and certainly since.

I knew there had been an investigation by the federal Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights; in fact, there were three investigations over the years. And, most shocking to me was an academic paper I found buried in the back of a box of documents in storage in the high school basement. It was a sharp critique of Shaker’s levels system written by a white Shaker graduate for a college class at Harvard—in 1969! His concerns were prescient and would be echoed over and over through the years. It was both amazing and also very sobering to read that.

I would mention one other thing. I came to believe that fostering a sense of belonging is critical to success for diverse school districts like this one. That’s not something you can do with a single program or initiative. It has to run through everything that happens in the community.

The thing that surprised me the most was how far back the Shaker schools’ tracking or levels system has been criticized as racially biased.

Can you tell us a little bit about Ludlow and how you came to put it in various parts of the book?

LM: Ludlow is a central part of the larger Shaker story. It was the first neighborhood where Black families moved in any numbers into Shaker Heights. The story of what the Black and white families living in Ludlow did to beat back the overwhelming pressures toward white flight, blockbusting and resegregation was truly remarkable. The ethos of Ludlow eventually spread to the rest of the community, as Black families began moving into other neighborhoods. Ludlow also comes back later in the book because in 1987 there was a school consolidation and Ludlow was one of four schools that closed. And it returns again at the end of the narrative with a fresh discussion of a new master facilities plan.

Closing schools is a big event in any community, but perhaps especially so in a place like Shaker. Could you say more about the closing part of the story as well?

LM: At a certain point in the 1980s, the district realized that they had a lot more capacity than they had students, and they needed to close schools from a financial point of view. Of course, closing schools is always a fraught proposition, and there were several efforts that failed for various reasons. But ultimately, the decision was made to close four of the nine elementary schools. At the time, it was seen as a very balanced solution. Looking back, you can ask whether it was as equitable as people felt it was at the time.

Looking back, you can ask whether it was as equitable as people felt it was at the time.

That was particularly true for one neighborhood called Moreland, which is the lowest-income part of Shaker and where students were and still are bused the furthest. This was done to create racially balanced schools, something Shaker has long been proud of.

However, one unintended consequence is that parents who have the greatest barriers to school involvement in terms of flexibility of their schedules and a lot of other issues are facing the biggest distances to getting there. And so that’s a conversation topic right now.

In recent years there was also a conversation about potentially reopening Ludlow Elementary School. Doing so would have meant closing a different school, which set off a firestorm of protest. These things are incredibly fraught.

Reading about what happened to Ludlow, I can’t help but think about “Nice White Parents.”

LM: “Nice White Parents” was a fascinating podcast. That said, I found it somewhat misleading — if you want some media critique. I actually did reporting in [District 15] as well, because this part of Brooklyn was the site of a very progressive and what turned out to be a largely successful integration plan for its middle schools. You actually had what you might call nice white parents who pushed to transform a system that was advantaging kids from families like theirs.

I think that a lot of the reporting for the podcast was done before that plan came along, and there was a lot of ugliness that preceded it, which was well documented and fascinating to hear. But I think [journalist Chana Joffe-Walt] was less focused on what wound up being a very important turn of events.

She does acknowledge this new plan in her final episode, but to my mind, the podcast was out of balance given that this particular district was the focus. All that said, very few other parts of New York City have done the same thing as District 15, and there are plenty of so-called nice white parents protecting their privileges.

“Nice White Parents” was a fascinating podcast. That said, I found it somewhat misleading.

What insights, lessons, or advice would you want to share with your fellow education reporters and editors, based on the experience of writing this book?

LM: To really understand what’s happening in a particular school or community, it really takes time. There are so many different constituencies and so many different perspectives. I don’t just mean in terms of race, but I mean, teachers versus parents versus students themselves, along with administrators and people who live in the community at large.

It takes time to really find the people who are thoughtful and to talk to enough people that you feel like you’ve captured the dynamics at play and the diverse points of view as well. So I would urge education editors to give their reporters lots of time to work on their stories! Of course, in today’s world reporters are stretched incredibly thin, so we have to carefully pick our long-term targets and do those stories really well.

What’s an example where extra time allowed you to find important nuance?

LM: One of the things I write about in the book is the effort to de-track classes and combine kids with mixed abilities into the same classrooms in Shaker. I talked to several Black parents about this issue who told me that this was actually not their priority. Some of them, in fact, outright opposed it. They said that what they were more concerned about was making sure that the right people were in the right classes and that some kids shouldn’t be in lower-level classes. You might think all Black families support de-tracking, but that’s not necessarily the case. That’s just one of many examples.

You might think all Black families support de-tracking, but that’s not necessarily the case.

What about moving over to the education beat? What surprises or nuances have you experienced? What insights have you gained?

LM: I was attracted to this beat because I thought covering schools would be an excellent way to write about so many of the social, economic and cultural pressures that define American life, and I have found that to be 100% true. On the other hand, I can’t say that I had the entire American school system shutting down amid a global pandemic on my Bingo card, so everything about this story has been a surprise on some level. I’ve been struck by the depth of the academic and social emotional losses over the last three years and believe that while the story will change and evolve, in one way or another it will be with us for a very long time.

Looking forward to the new school year, what topics do you think are most important for national education journalists to cover — and why?

LM: The two big stories are clear: continued pandemic recovery in all its dimensions and culture war politics. I know the culture war stories are not your favorite, but they are impacting life for students and parents in states across the country and are an important part of the macro political debate heading into the 2024 presidential race.

I also think the resurgent school choice movement is a big story, as a rising number of states adopt universal Education Savings Accounts, which give generous vouchers to any family regardless of income.

And violence in school continues to be a huge story, as well—both mass shootings (past and inevitably future) but also everyday acts of violence that get less attention.

Finally, since I have the opportunity, I’ll point readers to a series the Post is running this year on the rise of homeschooling and its implications. I’m working hard on those stories alongside my talented colleague Peter Jamison.

All that said, the wonderful thing about a beat like education is that there are all sorts of other stories to tell, and we are lucky to have so many talented reporters out there telling them.

Previously from The Grade

‘A gift’: John Woodrow Cox on covering school gun violence

A bold, imperfect start for the Washington Post’s Laura Meckler

Progress — and challenges — at the Washington Post

Nice white journalist

New book exposes flaws in media coverage of Northern integration efforts

New documentary highlights the need to deepen school integration coverage

Behind the scenes of ‘America to Me’

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alexander Russo

Alexander Russo is founder and editor of The Grade, an award-winning effort to help improve media coverage of education issues. He’s also a Spencer Education Journalism Fellowship winner and a book author. You can reach him at @alexanderrusso.

Visit their website at: https://the-grade.org/