To some, “ed finance” might sound like a back-office function best left to accountants toiling over spreadsheets in cubicles. Nothing could be further from the truth. School districts are major financial operations, and district leaders are the stewards of mega-budgets involving millions and sometimes billions of dollars. Their spending decisions are high stakes and high profile, and they are enormously consequential for students and their learning.

In practice, making decisions about how to spend public funds is a central function of district leaders, including superintendents and school boards. Take, for instance, the $2,400 per student, on average, that federal lawmakers delivered to districts in March 2021 as part of the American Rescue Plan. All across the country, district leaders have had to decide whether that money will be better spent hiring new staff or paying for part-time tutors, for recurring raises or one-time bonuses, to purchase laptops or issue a contract to manage the technology. Then, when that funding dries up in two years, countless districts will be making choices on how to trim their budgets.

At its most basic level, our education system depends on district leaders having financial fluency to leverage resources on behalf of students. And they must ensure their choices are equitable and financially sustainable, all while navigating a complicated landscape of stakeholder interests, advocacy demands, public reporting, and even career-ending missteps. And yet, most leaders haven’t been trained to make these kinds of strategic financial decisions. That’s because colleges of education, which prepare most of our aspiring district and school administrators and awarded more than 31,000 degrees in 2019 (DataUSA, n.d.), have largely bypassed this topic in their administrator-prep programs. That major omission leaves education leaders unprepared for their jobs.

Startling gaps in finance education

This year, with support from the federal Institute for Education Sciences, my team conducted an analysis of curricular offerings from 30 top-ranked institutions for graduate-level education administration, which often serve as models for lower-ranked programs (Silberstein, Roza, & Tollefson, 2022). To understand what finance preparation currently exists, and what’s missing, we compared the course content to a list of eight finance topical areas relevant to the role of school and district leadership. On average, relevant prep courses touched on just two of the eight areas.

Those financial topics that were included in university curricula tended to relate to the revenue side of the education finance equation, including training on revenue sources and state funding formulas. That’s curious because district leaders generally don’t control their revenues.

In contrast, we found scant coverage of the spending side of the equation, where district leaders play a much larger role. For example, most programs offered little to no skill-building on calculating spending tradeoffs, understanding key cost drivers, cutting budgets, and projecting equity implications from spending decisions. That’s a big mismatch and leaves district leaders unprepared to make sense of the financial topics that are the most relevant to their jobs.

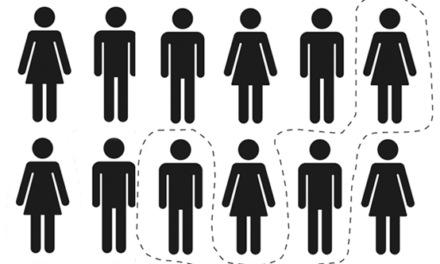

Principals, too, need preparation in finance. Larger districts tend to allocate a portion of their funds directly to schools (as happens in New York City, Atlanta, Chicago, Boston, Denver, and many others). In our center’s 2017-18 survey of principals from 14 districts in 11 states, fewer than half (46%) reported receiving any budget training at all in their certification or preparation programs (Jochim & Silberstein, 2020). Instead, these leaders tended to pick up whatever financial knowledge they have on the job — after they’d already assumed responsibility for spending decisions that have real impacts on real students. That seems deeply unfair to the principals, the students, and the communities they serve.

Further, thanks to a provision included in the federal Every Student Succeeds Act, states are now required to make their school-by-school spending data available to the public (Roza & Anderson, 2020), which will likely bring even greater pressure on districts to deliver resources more equitably to schools — pressure that leaders may not be prepared to handle. In a pilot program with 17 districts, we found that many superintendents, chief financial officers, budget directors, and other senior leaders had difficulty understanding the patterns that surfaced in new financial figures and identifying strategies to address inequities (Roza & Jarmolowski, 2021).

How has key financial content gone missing?

It’s probably not a surprise that faculty in education departments tend to gravitate toward foundational education topics like pedagogy and instructional leadership. These are, after all, education departments, and those topics are critical to any education leader.

Teaching instructional leadership must not come at the expense of teaching financial leadership.

But because education leadership brings such significant fiduciary responsibilities, teaching instructional leadership must not come at the expense of teaching financial leadership, even if doing so pushes faculty beyond their comfort zone. Research tells us that both matter for students and that financial decision making is essential to effective school leadership (Bloom et al., 2014; Grissom, Egalite, & Lindsay, 2021). By failing to provide would-be leaders with both, we’re effectively tying one hand behind their back.

The absence of education finance content in university education departments has made room for new post-preparation leadership programs to fill some of these gaps. These offerings tend to be unattached to university education departments and include topics that leaders didn’t get in their traditional prep programs. Examples include finance trainings offered by the AASA: The School Superintendents Association, the Association of School Business Officers, the Broad Academy (now at Yale), the Aspen Institute CFO Strategy Network, The Leadership Institute of Nevada, and a center I lead at Georgetown University called Edunomics Lab. While I don’t have participation figures for the other examples, an eye-popping 3,500 individuals over the last five years have participated in finance trainings and coursework delivered by Edunomics Lab alone.

In other words, the financial demands on K-12 leaders are growing and leaders know it. University education departments that don’t offer the financial training leaders need may lose participants to other universities that do or to other nontraditional leadership training programs.

Quick moves to ensure proper preparation

If they hope to prepare effective school and district leaders, then higher education faculty must start by recognizing that finance is an essential part of those roles. Leaders need to develop hands-on skills to manage budgets, construct cost-equivalent choices for investments, and understand key cost drivers and their implications for long-run fiscal forecasts. Building that capacity shouldn’t be left to on-the-job training. These finance topics must be included in the curriculum.

Education departments with limited finance depth among existing faculty needn’t start from scratch. The Institute for Education Sciences funded our center to develop skill-building finance modules, adapted from our certificate program and years of practitioner trainings. Faculty at select colleges of education around the country are currently piloting these free, off-the-shelf, highly adaptable modules (available at edunomicslab.org/elab-u), which are designed as ready-to-use lessons that can be incorporated into existing courses to meet practitioner needs. For higher education leaders looking to improve their offering, and for K-12 leaders looking to develop their expertise, they provide a place to start.

References

Bloom, N., Lemos, R., Sadun, R., & Van Reenen, J. (2014, November). Does management matter in schools. National Bureau of Economic Research.

DataUSA. (n.d.). General educational leadership and administration. Deloitte & Datawheel.

Grissom, J.A., Egalite, A.J., & Lindsay, C.A., (2021, February). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. The Wallace Foundation.

Jochim, A. & Silberstein, K. (2020, October). Taking stock of principals’ role in weighted student funding districts. Edunomics Lab.

Roza, M. & Anderson, L. (2020). New financial data spotlight the district role in distributing dollars across schools. Education Next.

Roza, M. & Jarmolowski, H. (2021, October). Four federal equity provisions and how they intersect. Comprehensive Center Network.

Silberstein, K., Roza, M., & Tollefson, J. (2022, February). Building financial leadership to do more fur students: Lessons from a landscape analysis of education finance curriculum in higher ed. Edunomics Lab.

This article appears in the April 2022 issue of Kappan, Vol. 103, No. 7, pp. 67-68.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Marguerite Roza

Marguerite Roza is a research professor at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., and director of the McCourt School of Public Policy’s Edunomics Lab.