Rising income inequality — and the higher stakes surrounding education — are driving parents to become more involved in their children’s lives.

“Mother hovers over me like a helicopter,” wails despairing teenager Lenard in the classic parenting guide Between Parent and Teenager by child psychologist Haim Ginott, which was a best seller when it was published in 1969. Despite Lenard’s complaints, parents at that time were generally far less obsessed than they are now with controlling their children’s lives. Today, the expression helicopter parenting is widely used to refer to the heavily involved, time-intensive, controlling child-rearing approach that has become widespread over the last three decades. The trend toward more intensive parenting is not just about supervising and protecting children but also about getting immersed in how children perform in school, which activities they pick up, and even who their friends and romantic interests are.

Parents’ invasion in their children’s lives can take different forms. An extreme version of the pushy and demanding parent is Amy Chua, a Chinese-American professor at Yale Law School. Her best-selling 2011 book, The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, makes a brilliant (and humorous) defense of the stereotypically tough, East Asian approach designed to produce self-confident, hard-working children devoted to success. While Chua’s style is often associated with Chinese culture, intensive parenting has become increasingly popular across a number of industrialized countries, albeit with varying characteristics. Some parents suffocate their children with attention and advice but are more protective than forceful. For example, Fabrizio knew of an Italian mother who rented an apartment in the village where her 25-year-old son was doing his military service so that she could prepare warm dinners for him to recover from the fatigue of hard training. If all Italian mothers were this protective, the government might have to arrange special camps for accompanying mothers along the front line.

The lion’s share of the new intensive parenting consists of pushing children to become early achievers.

The psychologist Hara Estroff Marano (2008) has labeled this child-rearing approach overparenting. In her book with the contentious title A Nation of Wimps: The High Cost of Invasive Parenting, she blames overparenting for the supposed loss of independence of young American adults. Indeed, she asserts that parental intervention has extended its scope progressively into adulthood and that parents increasingly get involved in their children’s education well beyond high school and college. For instance, a growing number of parents meddle in their children’s admission process to graduate schools, visiting campuses and calling up and asking to meet with graduate admissions officers. Marano (2014) relates with horror that this parental invasion has now reached business and law schools, institutions that traditionally value applicants’ motivation and self-reliance.

Empirical evidence on intensive parenting

Parents who call up graduate admissions officers or prepare warm meals for their children in military service make for telling anecdotes, but as economists, we look for systematic evidence to corroborate the view that this is symptomatic of a more general pattern. When we consider a change in parenting and a potential explanation, we look at the data from many parents and children to see if there is real evidence that the explanation is credible.

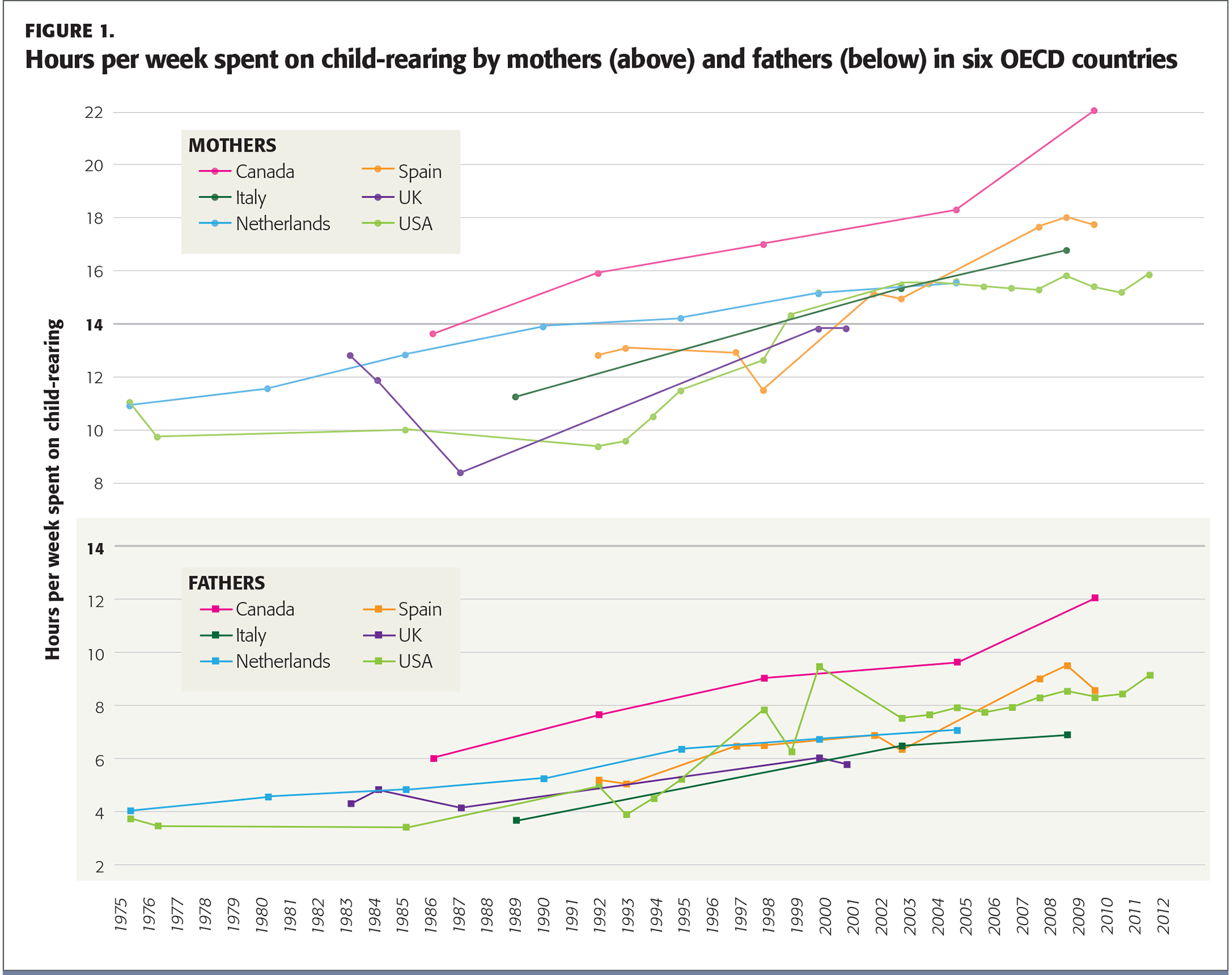

The data confirm that over recent decades, parents have devoted an increasing share of their time to child-rearing.

To measure whether parenting really has gotten more intense in recent decades, the natural first step is to look at survey diaries that record how people spend their time. (Our analysis of parents’ time diaries builds on the important contribution of the economists Garey and Valerie Ramey, 2010.) In a growing number of countries, statistical offices collect information on how people spend the 24 hours that they have at their disposal each day. For instance, in the United States, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has an ongoing project called the American Time Use Survey (Hamermesh, Frazis, & Stewart, 2005), and similar projects exist in other countries. The data confirm that over recent decades, parents have devoted an increasing share of their time to child-rearing.

Figure 1 shows the weekly hours spent by mothers (upper panel) and fathers (lower panel) on child-rearing in Canada, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The plots for the Netherlands and the United States are especially revealing because the data go back all the way to the 1970s. In 2005, Dutch mothers spent about four more hours a week on childcare than in 1975, while Dutch fathers spent three extra hours. This means that, on average, children in 2005 got a full extra hour per day of interaction with their parents compared to children in 1975. In the United States, the increase in time spent on parenting is even larger: Between the late 1970s and 2005, the time mothers and fathers spent per week with their children went up by approximately six hours each, which translates into an additional hour and 45 minutes of parent-child interaction per day. For Canada, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom, data are only available for shorter time spans, but in all cases, there is clear evidence of an increasing trend in time spent on parenting.

The effect of this increase on the attention received by each child is further amplified if one takes into account the decline in fertility that took place during the same time. In the Netherlands, the average number of children per family (as measured by the total fertility rate) fell from 3.1 in 1960 to 1.7 in 2014, and in the United States it fell from 3.7 to 1.9 during the same period. If one takes into account that today there are fewer children to care for, our estimate that parent-child interactions went up by one to two extra hours a day is actually an understatement of the additional attention received by each child.

Another element to take into account is the “quality” of the time that adults spend with their children — watching TV together is different from truly engaging with a child in a joint activity. This dimension is harder to quantify, but certainly parents are, on average, better educated today than a few decades ago, which is likely to be related to the quality of parent-child interactions. Parents also have access to cheaper and more effective educational tools. In fact, an entire industry has sprung up that develops educational toys, websites, apps, and electronic devices designed to “stimulate” children and assist in their development. However, the net effect of these changes is hard to assess, as surely technology is also prone to misuse. A BBC News Education Report from Judith Burns (2017) argues that overuse of smartphones by parents disrupts family life. She quotes the results of a survey in which more than a third of adolescents said they had asked their parents to stop checking their devices all the time. This calls into question whether the quality of child-adult interaction is actually higher than in the past.

Another interesting observation is that in both the United States and the Netherlands, the time spent on childcare activities has increased more for college-educated parents than for less-educated parents. In the Netherlands, in 1975, college-educated mothers spent one hour a week more on child-rearing activities than did non-college-educated mothers. For fathers, the educational gap in childcare time was half an hour. In the first decade of the current century, the gap went up to about two and a half hours for both mothers and fathers. During the same period, the change was even larger in the United States. In the 1970s, less- and more-educated parents spent about the same time on child care. Today, there is a gap of more than three hours between these groups.

The diaries also tell us what activities parents do with their children. Back in 1976, the average couple in the United States spent two hours a week (76 minutes for mothers and 43 minutes for fathers) on playing, reading, and talking to their children, and 17 minutes a week (10 and 7 minutes, respectively) on helping them with homework. In 2012, the average couple spent six and a half hours a week (204 and 184 minutes) on playing, reading, and talking to their children, and more than an hour and a half (65 and 31 minutes) on helping them with homework. Overall, the time American parents spend on these activities went up by a factor of 3.5, from less than two and a half hours to more than eight hours per week.

The impact of intensive parenting is reflected in children’s experiences. In the United States, the percentage of kids walking or biking to school fell from 41 percent in 1969 to 13 percent in 2001 (Gibbs, 2009). Among six- to eight-year-old Americans, free playtime decreased by 25% between 1981 and 1997, whereas time spent on homework more than doubled. This is interesting, as one might have suspected that parents have simply learned to enjoy fun and games with their children. They may do that, too, (especially with games that have a high educational content that parents enjoy more than children do), but the lion’s share of the new intensive parenting consists of pushing children to become early achievers.

Our theory is that parents are responding to changes in incentives, especially concerning the economic environment in which their children will live as adults.

In sum, the evidence shows unequivocally that parents spend much more time with their children today than a few decades ago. The question is: Why? Are today’s parents wiser, more aware, perhaps even more loving than their own parents were? Is this increase in parent-child interaction time bringing up a great generation of super-educated and highly motivated adults? Or rather, as suggested by critics, is this just the sign of an irrational frenzy that will grow a generation of “mama’s boys” and “daddy’s girls” lacking independence and imagination?

Our theory is that parents are responding to changes in incentives, especially concerning the economic environment in which their children will live as adults. What happened that makes parents increasingly obsessed with what their children are up to? To answer this question, we go back in time.

Rising inequality in the 1980s

The 1980s were a turning point for Western countries in political, economic, and cultural terms. During that time, there were also sharp increases in economic inequality, particularly in the United States and the United Kingdom. In the United States, the ratio of income shares going to the wealthiest 10% versus the poorest 10% more than doubled between 1974 and 2014 (from 9.1 to 18.9). In the United Kingdom, it increased from 6.6 to 11.2 during the same period. In Italy, it went up from 7.7 in 1984 (first available data) to 12.6. Even countries that were traditionally highly egalitarian witnessed an increase in inequality: The ratio increased from 3.5 to 7.3 in Sweden, and from 5.3 to 7.8 in the Netherlands.

A significant portion of the surge in income inequality during the 1980s was driven by increasing returns to education. In the United States, the ratio between the average wages of college-educated workers and those of high school graduates increased from 1.5 to 2. In addition, there was a sharp increase in the return to postgraduate education (Acemoglu & Autor, 2011). The British economists Joanne Lindley and Steve Machin (2011) show that in both the United Kingdom and the United States the wage premium for workers with postgraduate education has increased relative to workers with only a college degree. In the early 1970s, the average wages of the two groups were about the same, whereas in 2009 a worker with a postgraduate qualification earned, on average, a third more than a college graduate (and as much as 136% more than a high school graduate). And these figures likely underestimate the value of a postgraduate degree, since many of those earning these degrees end up in academic or teaching jobs that are not very highly paid (except for a few elite schools) but are associated with significant nonmonetary benefits (such as prestige, research freedom, and job security). Today, the economic return of postgraduate education is very high, and the increasing appeal of advanced education is apparent in that the share of workers holding a postgraduate degree has boomed over the years.

Another contributing factor to the rise in overall inequality is an increase in wage inequality among people with the same education level. This shift is explained both by higher pay differences across subjects (such as the significant increase in wages for graduates with finance and engineering degrees relative to those with degrees in humanities and social sciences) and by pay differences across graduates who obtained their degrees from different universities (Rendall & Rendall, 2016). All these changes to inequality have a common consequence: They increase stakes in education.

We believe that the change in economic conditions is responsible for at least part of the increasing investments parents make in their children. For this argument to be credible, though, it is crucial that parenting styles really matter in terms of success in school and life. How strong is the evidence that an intensive parenting style or, more broadly, the time parents spend interacting with children improves their school performance? A number of studies in developmental psychology suggest that the evidence is in fact quite strong (e.g., Chan & Koo, 2010; Dornbusch et al., 1987; Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1991).

Taking stock

Our own research looked at data from the Program for International Student Assessment and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997, which confirm that parenting styles have significant impacts on school performance and risky behavior (Doepke & Zilibotti, 2019). The children of involved parents who adopt an authoritative parenting style are more likely to do well in school and to receive higher degrees, and they are less likely to engage in potentially harmful risky behaviors. In terms of education outcomes, the children of permissive parents rank in the middle, and the children of parents who are authoritarian but uninvolved do least well. All the results hold true when we hold constant the parents’ education background.

All these pieces of evidence are consistent with our general thesis: There has been a shift in the intensity of parenting, as measured by the time parents devote to interacting with their children. This shift has occurred in a period characterized by increasing inequality, a booming return to education, and generally higher stakes to bringing up children. As a result, parents have become increasingly worried about their children’s school performance and have responded by engaging in more intensive parenting, choosing parenting styles that are conducive to children doing well in education. Hence, the rise of helicopter parents can be understood as a rational response of parents to a changed economic environment.

References

Acemoglu, D. & Autor, D. (2011). Skills, tasks, and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings. In O. Ashenfelter & D.E. Card (Eds.), Handbook of Labor Economics 4 (pp. 1043–1171). Amsterdam: North Holland.

Burns, J. (2017, April 23). Parents’ mobile use harms family life, say secondary pupils. BBC News.

Chan, T.W. & Koo, A. (2010). Parenting styles and youth outcomes in the UK. European Sociological Review, 27 (3), 385-399.

Chua, A. (2011). Battle hymn of the tiger mother. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

Doepke, M. & Zilibotti, F. (2019). Love, money, and parenting: How economics explains the way we raise our kids. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Dornbusch, S.M., Ritter, P.L., Liederman, P.H., Roberts, D.F., & Fraleigh, M.J. (1987). The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Development, 58 (5), 1244-1257.

Gibbs, N. (2009, November 30). The growing backlash against overparenting. Time.

Ginott, H.G. (1969). Between parent and teenager. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Hamermesh, D.S., Frazis, H., & Stewart, J. (2005). Data watch: The American Time Use Survey. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19 (1), 221-232.

Lamborn, S.D., Mounts, N., Steinberg, L., & Dornbusch, S.M. (1991). Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development, 62 (5), 1049-1065.

Lindley, J. & Machin, S. (2011). Rising wage inequality and postgraduate education (Discussion Paper no. 1075). London, UK: Centre for Economic Performance.

Marano, H.E. (2008). A nation of wimps: The high cost of invasive parenting. New York, NY: Broadway Books.

Marano, H.E. (2014, January 21). Helicopter parenting — It’s worse than you think. Psychology Today.

Ramey, G. & Ramey, V.A. (2010). The rug rat race. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 129–176.

Rendall, A. & Rendall, M. (2016). Math matters: Education choices and wage inequality (working paper). Monash University.

Steinberg, L., Mounts, N.S., Lamborn, S.D., & Dornbusch, S.M. (1991). Authoritative parenting and adolescent adjustment across varied ecological niches. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 1 (1), 19-36.

Note: This article is adapted from Love, Money, and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids by Matthias Doepke and Fabrizio Zilibotti. Copyright © 2019 by Matthias Doepke and Fabrizio Zilibotti. Published by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

Citation: Doepke, M. & Zilibotti, F. (2019). The economic roots of helicopter parenting. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (7), 22-27.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Fabrizio Zilibotti

FABRIZIO ZILIBOTTI is the Tuntex Professor of International and Development Economics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He and Matthias Doepke are the authors of Love, Money, and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids .

Matthias Doepke

MATTHIAS DOEPKE is a professor of economics at Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill. He and Fabrizio Zilibotti are the authors of Love, Money, and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids .