Prospective teachers share how the pandemic has affected their perceptions of teaching and their interest in entering the profession.

Even in the best of times, many school districts across the U.S. have struggled to staff their classrooms with the teachers they need. In particular, teachers of math, science, and special education tend to be in short supply, and Black, Latinx, Asian, and Indigenous educators (whose presence is associated with higher academic achievement and increased graduation rates, especially among students of color) have long been underrepresented in the profession (Gershenson, Hansen, & Lindsay, 2021; Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, & Carver-Thomas, 2019). Further, schools serving high percentages of socioeconomically disadvantaged and racially/ethnically minoritized students have been hit hardest by shortages of high-quality, diverse teachers (Dee & Goldhaber, 2017; Lankford, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2002).

These struggles are likely to persist and intensify. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, scholars predicted a national teacher shortage as high as 316,000 by 2025 (Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, & Carver-Thomas, 2016). The onset of the pandemic in spring 2020 appears to have made matters worse, with recent studies suggesting that the pandemic may be prompting teachers to leave the profession earlier than anticipated and at a higher rate than usual (Pressley, 2021; Steiner & Woo, 2021; Walker, 2021). These studies indicate that the pandemic is having negative impacts on teacher retention rates. As yet, however, little is known about how the pandemic may be affecting teacher recruitment.

To address this knowledge gap, we recently conducted a study of University of Maryland undergraduate students to find out how a variety of factors, including the pandemic, have influenced their desire to pursue teaching as a career. (For a more detailed description of our research, see Bill et al., 2021.) More specifically, we surveyed 1,676 undergraduates on their changing views of the teaching profession, and we then conducted focus-group discussions with 142 of the 1,254 survey respondents who had indicated an interest in teaching on our survey — we refer to these 1,254 respondents as undergraduate prospective teachers (UPTs).

The UPTs in our study expressed varying degrees of interest in teaching: 44% said that they had considered a teaching career in the past but had decided to pursue a different path; 13% reported that they were considering teaching as one of multiple career options; 35% expressed a desire to teach in the future (after working in another field); and 8% reported that they were actively enrolled in a teacher preparation program, with the intent to go directly into a teaching career. As a whole, though, their shared interest in the profession makes them an important group to understand if we hope to alleviate teacher shortages (U.S. Department of Education, 2015).

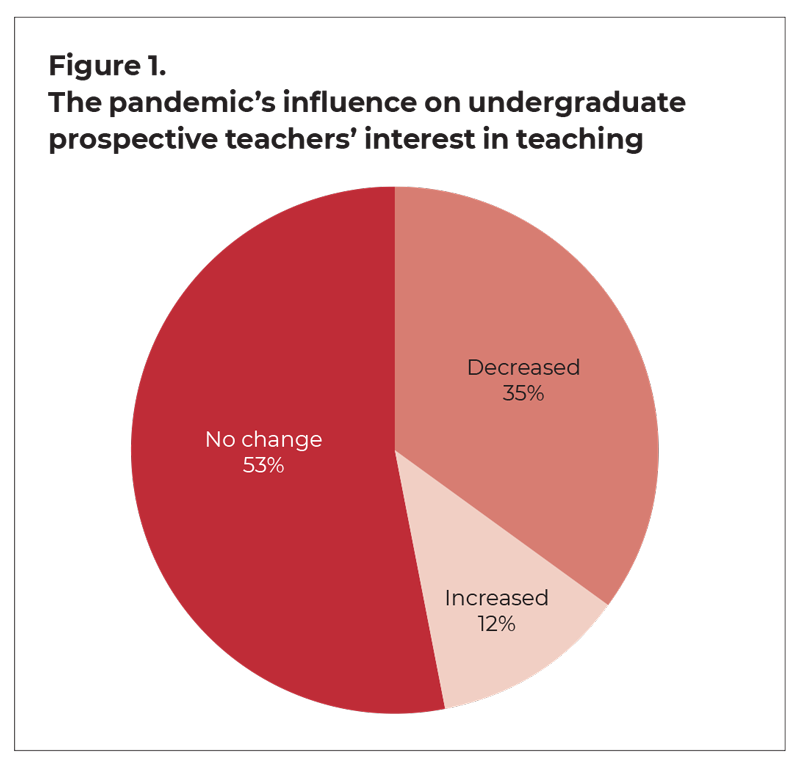

Although the majority of our survey respondents reported that the pandemic did not change their interest in teaching, it was an influential factor for many.

Indeed, data from our study offer valuable insights into these undergraduates’ interest in and perceptions of the teaching profession in the COVID-19 era. On one hand, the pandemic has increased their respect for teachers and the work they do; on the other hand, it has magnified their concerns about the heavy workload of teaching and the general public’s lack of respect for teachers. Although the pandemic’s lasting effects on teacher recruitment remain to be seen, our findings reaffirm that these issues are key factors in the career decisions of UPTs. If we hope to attract more of these prospective teachers into the teaching profession, then such concerns warrant serious attention.

The pandemic’s effects on interest in teaching

Although the majority of our survey respondents reported that the pandemic did not change their interest in teaching, it was an influential factor for many. More than a third (35%) of UPTs reported becoming less interested in teaching because of the pandemic, while 12% reported becoming more interested in the career (see Figure 1). Our data shed light on the reasons for these responses.

Unchanged views

For a variety of reasons, more than half (53%) of the prospective teachers in our study indicated that the pandemic has not changed their interest in teaching. For instance, some who still intended to pursue teaching described the pandemic as a rare, “temporary” situation that will end before they begin their careers, and others said that the pandemic did nothing to override the attractive features of a teaching career, like making a difference in students’ lives. As one said, “Good teachers are needed right now, especially since students are suffering from lack of motivation and stress due to COVID-19. I want to become a teacher, despite these challenges, so I can help students.”

Others had decided not to go into teaching before the pandemic. As many of them pointed out, the pandemic response did nothing to fix the most unattractive features of teaching that had turned them away from the career in the first place, namely the low salary and the public’s lack of respect for teachers. As one UPT put it, “I have always wondered whether I should be a teacher, but COVID-19 hasn’t changed that at all. The main reason I don’t want to is because of the pay compared to a job in a tech industry.” Said another, “It didn’t sway me in either direction, but it . . . was another example of how teachers are kind of just disrespected.”

Decreased interest

More than a third of UPTs indicated that the pandemic decreased their interest in teaching due in large part to their perceptions of “how teachers are being treated during this time.” For example, some participants thought policy makers’ responses to the pandemic put teachers at risk and illustrated school districts’ and the broader public’s disrespect of the teaching profession. As one explained:

If anything, COVID-19 has decreased my interest in becoming a teacher because teachers were put in danger because some schools required in-person classes. While I value my K-12 teachers and hold them to a high regard, it seems like many school districts and society in general does [sic] not. Teachers are so important . . . they deserve better and more respect.

Others reported that online teaching made it “much harder” to establish relationships with students, which was, in the eyes of some, the “only really good thing about teaching.”

Increased interest

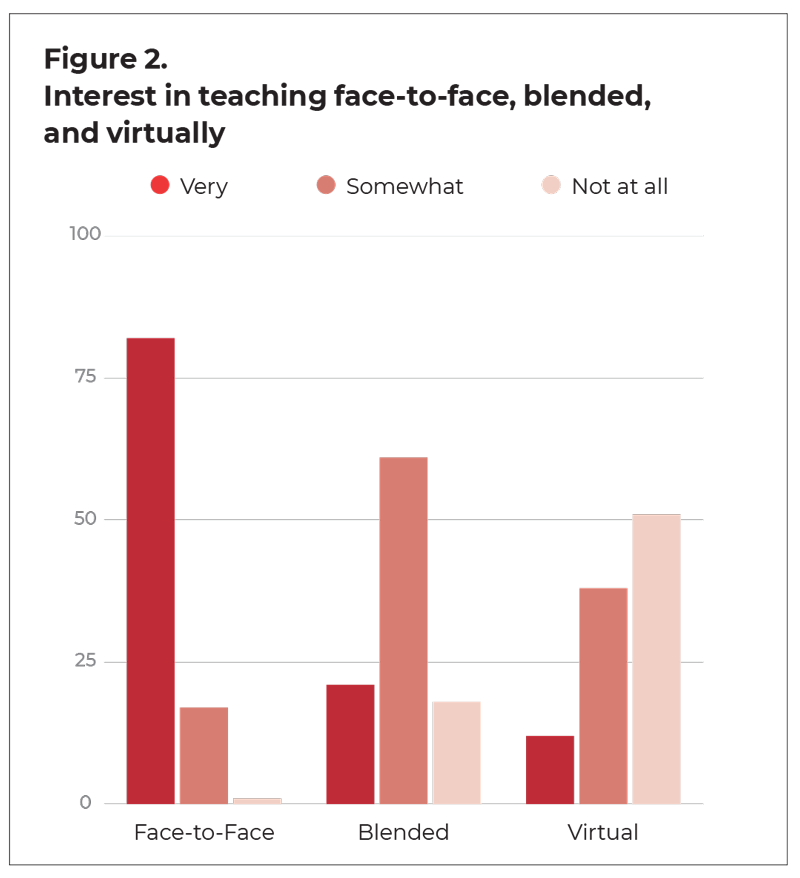

The pandemic increased interest in a teaching career for about 12% of prospective teachers in our study, in part because of the opportunity to teach virtually. Although nearly all survey respondents (99%) expressed interest in teaching face-to-face, almost half noted that they were somewhat or very interested in teaching virtually, as well; and more than 80% were somewhat or very interested in teaching in a blended format (see Figure 2). Some survey respondents perceived teaching as “more flexible and just as rewarding” in a virtual environment, and a small number of focus-group participants said the prospect of virtual teaching increased their interest in the profession. For example, one participant had begun “seriously considering teaching” as a result of the pandemic because the new virtual environment “made it possible to be more fluid, to teach fewer hours, remotely, or in informal programs.”

The opportunity to make a difference with students amid the challenges and uncertainties of the pandemic also spurred increased interest for this subset of respondents. As they explained:

I see on social media what teachers are doing for their students and think how much they care about their students and that I could also do, with my life, something that makes such a difference.

I’ve seen a lot of extreme measures that teachers are taking, and I have a lot of respect for them for doing that. And so it’s hard — [the pandemic is] a deterrent, but it’s also kind of a motivator. I want to be that change.

Finally, a small number of UPTs said in write-in survey responses that they have become more interested in teaching because they perceive it to be a stable job and “it’s hard to find jobs right now.”

The pandemic’s effects on perceptions of teaching

The pandemic increased UPTs’ respect for teachers because it highlighted the importance of their work and demonstrated how quickly they can and will adapt to meet students’ needs. But at the same time, the pandemic magnified existing concerns and raised new ones about the difficulty of teaching and the disrespect teachers endure.

Reaffirming respect

In our focus-group discussions, UPTs talked frequently about how the pandemic renewed their respect for teachers because it reminded them “how important teachers are to our society,” how they are “shaping the leaders of tomorrow,” and how they can play an important role in advancing social justice. As one participant said:

I think COVID has made me see how important teachers are . . . in terms of the racial justice and Black Lives Matter stuff. So many of our own presumptions and our perspective on the world is [sic] shaped in elementary school. . . . So if you don’t have the right teachers who are teaching you to be open-minded and to respect everyone equally, then it’s going to have an impact on you [for] the rest of your life.

Some UPTs also described having a “newfound respect” for teachers because they demonstrated “flexibility” throughout the swift and tricky transition to virtual teaching. It was “very commendable how the teachers have adapted,” according to a number of UPTs, and it was inspiring to see how they were taking “extreme measures” to assist their students.

Growing concern

Although many UPTs acknowledged that teaching has always been a difficult job, they believed that it has become harder in the COVID-19 era because of the rapid, at times inadequately supported, transition to online and hybrid learning and the added pressure to maintain COVID-safe practices in classrooms. Most viewed pandemic teaching as “stressful” and “exhausting” work that imposed a heavy “emotional toll” on teachers. They agreed that “it’s a lot to take on, that job.”

Focus-group participants also reported concerns about the “lack of respect” teachers encounter, including the “bad-mouthing” of teachers they heard throughout the pandemic. As one UPT expressed it, “Why go to school and get a degree to get disrespected every day?” Many noted how “some people in society see teachers as basically glorified day care,” as “incompetent,” or as “not doing enough” to help children learn online. Others described a disconnect between these pejorative messages and the tireless efforts they saw teachers putting into their jobs. One UPT, who was a student teacher in a virtual classroom during the pandemic, said of her mentor teacher:

I can see how much outside-of-class time she’s putting in for the students. . . . So it’s just really discouraging to hear when people still aren’t respectful of teachers, even in a pandemic, when there’s so much going on. Like, if quality teachers aren’t given respect in this scenario, when are we ever gonna receive respect?

Respondents also noted that it was disrespectful for administrators and policy makers to push for a return to in-person schooling before vaccinations were available for teachers and support staff and without safety plans, adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), and other resources. One participant explained:

I’ve seen . . . the media emphasizing how teachers have to pick up the slack . . . when the school system doesn’t give them proper PPE in the classroom. I’ve seen teachers that had to set up, like, their own methods of social distancing. And I saw one teacher that put together shower curtains and PVC pipes to separate the kids in the classrooms. . . . I think the media really emphasizes how above and beyond teachers have to take it upon themselves, to go out of their way to take care of the kids. And that’s a good thing on the teacher’s part, but also, like, kind of shows systematically how teachers aren’t really, like, supported enough.

Other UPTs said that a lack of resources and training to support teachers’ abrupt transitions to virtual learning also indicated disrespect. Some perceived that teachers were “thrown under the bus with the virtual world” because they were not “provided resources to teach well totally from the get-go.”

Teachers’ low salaries added insult to injury because, as one UPT claimed, “teachers aren’t getting paid enough to be frontline workers.” Many of respondents said that the low salary of teaching, coupled with the disrespect they observed, was a “punch in the gut.” Several argued that “now’s the time when we should be paying teachers more,” particularly because of “all the hard work they’re putting into teaching their students.” One UPT’s comment sums up these widely shared perspectives: “It’s sad to see that, like, society views [teachers] as something less and that they aren’t getting paid what they should be getting.”

Implications for teacher recruitment

Because undergraduate prospective teachers (UPTs) are a critical component of the teacher pipeline, we sought to understand how the pandemic might be affecting their interest in and perceptions of teaching. Our findings suggest that the pandemic may be making it more difficult to recruit UPTs into the profession. Although roughly half of the UPTs we surveyed reported that COVID-19 had not affected their interest in teaching, that’s not a reassuring finding, given that so many of these respondents had already decided not to pursue a teaching career.

Notably, the pandemic increased interest in teaching for about 12% of survey respondents. Of those, some found the flexibility of virtual and hybrid teaching environments to be intriguing, some were eager to make a difference in students’ lives, and some perceived teaching to be an attractive and stable career. On the other hand, more than a third of UPTs reported that their interest in teaching decreased during the pandemic, mainly because the COVID-19 response reinforced their deep concerns about teaching’s heavy workload and low reward in terms of social respect and salary. In addition, the pandemic created new concerns about school systems’ lack of COVID safety protocols and inadequate support during the swift transition to virtual learning.

These findings should prompt policy makers and education leaders to promote initiatives that could alleviate at least some of the issues UPTs identified as disincentives to teach. Improving support for teachers and advancing policies that prioritize teachers’ well-being may address UPTs’ apprehensions about the difficulty of teaching. And while policy makers cannot mandate respect for teachers, they can address some of the factors that our participants saw as signals of disrespect, most notably teachers’ low salaries, the perceived pressure for teachers to return to classrooms they saw as unsafe, and the uneven support provided amid the rapid changes in teaching environments. While no one has a silver-bullet solution to the nation’s teacher recruitment woes, policies that address UPTs’ concerns about salary, safety, and support may increase the likelihood that members of this sizable pool of prospective teachers will pursue a teaching career.

Further, UPTs’ interest in blended instruction — and, to a lesser extent, virtual teaching formats — suggests that adjustments to the structure of teaching may help expand the teacher workforce. Emerging research (e.g., Bueno, 2020) explores the effects of blended and virtual teaching formats on student outcomes, but we know little about whether or how these formats might influence the labor market. Future studies are needed to understand to what degree UPTs might prefer virtual teaching opportunities and whether new teaching formats might attract more of them to the profession.

Although the pandemic has complicated teacher recruitment and disrupted how school systems deliver essential programs and services, it has also given us an opportunity to rethink how we might structure education investments in ways that make teaching a more appealing career. Federal COVID-19 relief funds have created opportunities for many schools to enhance working conditions and expand supports for teachers while mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on school communities (Turner, 2021). Changes such as these might help prevent the pandemic from becoming yet another drain on the teacher pipeline.

References

Bill, K., Bowsher, A., Rice, J.K., & Malen, B. (2021, March). Advancing equity: Expanding and diversifying the teacher workforce [Paper presentation]. Association of Education Finance and Policy Annual Conference, Virtual.

Bueno, C. (2020). Bricks and mortar vs. computers and modems: The impacts of enrollment in K-12 virtual schools. (EdWorkingPaper: 20-250). Annenberg Institute at Brown University.

Dee, T.S. & Goldhaber, D. (2017). Understanding and addressing teacher shortages in the United States. The Brookings Institution.

Gershenson, S., Hansen, M, & Lindsay, C.A. (2021). Teacher diversity and student success: Why racial representation matters in the classroom. Harvard Education Press.

Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2002). Teacher sorting and the plight of urban schools: A descriptive analysis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24 (1), 37-62.

Pressley, T. (2021). Factors contributing to teacher burnout during COVID-19. Educational Researcher, 50 (5), 325-327.

Steiner, E.D. & Woo, A. (2021). Job-related stress threatens the teacher supply. RAND Corporation.

Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the US. Learning Policy Institute.

Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2019). Understanding teacher shortages: An analysis of teacher supply and demand in the United States. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27 (35).

Turner, C. (2021, September 1). Schools are getting billions in COVID relief money. Here’s how they plan to spend it. NPR.

U.S. Department of Education. (2015). Title II Higher Education Act news you can use: Enrollment in teacher preparation programs [Issue brief]. Author.

Walker, T. (2021, June 17). Educators ready for fall, but a teacher shortage looms. NEA Today.

This article appears in the March 2022 issue of Kappan, Vol. 103, No. 6, pp. 36-40.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Kayla Bill

KAYLA BILL is a Ph.D. candidate in education policy at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Amanda Bowsher

AMANDA BOWSHER is a research affiliate at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Betty Malen

BETTY MALEN is a distinguished scholar-teacher at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Jennifer King Rice

JENNIFER KING RICE is senior vice president and provost and a distinguished scholar-teacher at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Jason E. Saltmarsh

JASON E. SALTMARSH is a Ph.D. candidate in education policy at the University of Maryland, College Park.