A longtime school librarian breaks down little-understood procedures that are often left out of media coverage.

By Becky Calzada

I’ve been a school librarian for more than 20 years.

It’s a specialized field that required me to take graduate-school courses in children’s and young-adult literature.

But another aspect of this job that I learned – one that is seldom addressed in news coverage about library challenges – is the importance of following school policies to clearly define and communicate how to select books.

That includes having clear expectations if a parent raises a concern about a book.

Informal and formal reconsideration processes are an integral component of any collection development policy.

That way, any books in question undergo a thorough review via a committee that is representative of the greater community.

All schools have processes in place to decide how to proceed regarding book challenges.

However, there are documented cases in which schools have not followed their own procedures. They’ve simply removed a book (or books).

There are documented cases in which schools have not followed their own procedures.

Here’s how it used to work:

Before 2021, a parent with a concern reached out to the campus librarian or a principal.

A meeting would be scheduled to share the concerns and a follow-up conversation occurred. Questions were asked by a librarian to gain understanding or to clarify the problem so there was no confusion. The conversation exchange was grounded in seeking to understand the parent’s concern, sharing selection processes, and offering options for next steps.

Steps might include the librarian and the parent reading the book together, with the librarian sharing the professional reviews to confirm grade-level placement with the parent and a follow-up meeting to discuss the book.

Another action might include the parent deciding to restrict material for their student rather than filing an official book challenge.

However, a parent could submit a book challenge to have the book placement formally reviewed by a district committee — typically composed of a principal, librarian, teacher, and parents in the community. In some areas, there is also student representation on the committee.

In my 12 years of experience as a library coordinator, I have not seen any removals of books from our libraries.

A title may be moved from elementary to middle school or middle to high school, but we’ve never completely removed a book title at any reconsideration committee meeting in the district.

In my 12 years of experience as a library coordinator, I have not seen any removals of books from our libraries.

My experience is not universal, however.

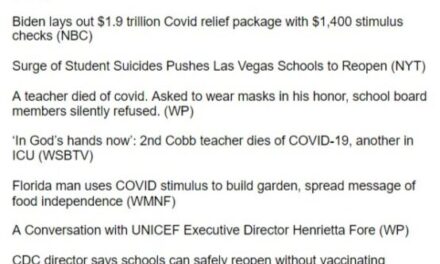

Since 2021, the number of book challenges has skyrocketed, and the procedures for addressing them appear to have broken down.

There were 729 attempts to ban or restrict books or other library materials in 2021. That jumped to 1,269 in 2022, and preliminary data from January through August 2023 shows 695 attempts from January to August this year.

In addition, there have been cases of documented harassment or death threats against librarians who have spoken out.

According to PEN America, book challenges most often involve books with LGBTQ+ themes or those that prominently feature characters of color. Those are followed by challenges over sexual content and materials in which the primary theme is racism.

Book challenge policies still exist, but unfortunately, we are hearing more and more about books being removed, apparently without following established procedures.

There are documented cases where books have been removed from campuses without following designated policies or due process for the book.

The removal is based on the reading of a few passages at a school board meeting which goes against legal precedent of Miller v. California, which requires looking at the work as a whole.

That’s why it’s so important for reporters to know how book challenges are supposed to be handled by schools. Stories about these controversial challenges should make it clear when school districts are ignoring or going against their own policies.

It’s so important for reporters to know how book challenges are supposed to be handled by schools.

Many of those policies allow a panel called a reconsideration who read the book in its entirety, come together, and follow an agenda to determine placement or even removal. In my community, we even go as far as having a lottery to choose which teachers and parents are selected for the committee.

Once a challenge is received, books are gathered for the committee to read, names are drawn, and books are sent to committee members with instructions to read the entire book. The complainant’s concern is not included, so all committee members read the book and come to their own conclusions regarding it.

Committee members often can guess what the complaint has been, but that’s not confirmed until a week before the committee meets, when the complainant’s concerns are shared along with professional library reviews, board approved selection policies, and any district guiding documents referenced in the book selection.

The committee then comes together to make a decision. The entire process can take 4-6 weeks per book.

The entire process can take from 4-6 weeks per book.

I’ve participated in many reconsideration meetings as a note-taker.

Sometimes there are disagreements or questions. But always, participants are thoughtful, come informed, and understand the responsibility and seriousness as a reconsideration committee participant.

Participants respect the norms which allow everyone to participate and truly want to offer the complainant options that will be helpful in building understanding on their final decision.

It’s also important for the public to know whether a particular challenge is to a book that is part of the curriculum or — as is usually the case — a library book.

Why does this matter? Because all students in a class must read the materials assigned for that course while libraries are places of voluntary inquiry. No student is ever forced to check out a particular book.

Author and activist George M. Johnson offered an analogy at the 2022 SXSW Edu panel keynote using ketchup as an example: There are many ketchup brands in a store, but a store owner wouldn’t ban one brand just because a few people didn’t like its flavor.

There are many ketchup brands in a store, but a store owner wouldn’t ban one brand just because a few people didn’t like its flavor.

The same goes for libraries; librarians recognize parents’ right to choose for their families. In fact, it’s an aspect of many collection development policies.

If there’s a parental concern about a library book, no matter what age level, there’s always an opt-out available and an alternate book that can be used.

It’s when a personal right infringes on the rights of others — by attempting to remove a book that others might want to read — that librarians intervene. Intellectual freedom is a foundational belief for librarianship and guaranteed by the First Amendment.

“When we filled these places with books, we were not saying, ‘Every book on these shelves is magnificent!,’” wrote Alexandra Petri in the Washington Post earlier this year. “We were saying, ‘Isn’t it magnificent that there are so many books on these shelves, and people can decide what they think of them for themselves?’”

Books are tools for understanding complex issues. Rampant censorship limits young people’s proper awareness of the world as it really exists.

Becky Calzada is the District Library Coordinator in Leander, Texas. She is the 24/25 AASL President-Elect and was honored by People Magazine in their 2023 Women Changing the World portfolio.

Previously from The Grade

How to improve book ban coverage (by Cafeteria Duty)

Book ban pitfalls

Book ban corrections

Book ban pushback

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

The Grade

Launched in 2015, The Grade is a journalist-run effort to encourage high-quality coverage of K-12 education issues.