Students want to know the relevance of what they learn at school. Educators can help them understand the ‘why.’

Why do I have to learn this?” is one of the most consistent and persistent questions students ask us. As former teachers and as researchers who study motivation in school, we’ve heard this question from our students; from the many students who have participated in our research studies; and, in the case of one author, from his own children during their K-12 education.

This is a reasonable question for students to ask. Few of us want to sit through professional development sessions that we see as irrelevant to our work. We would not want to read a book or watch a television show that we didn’t enjoy or find useful. So why would our students want to learn about topics that don’t seem relevant to them?

It’s essential that students understand why they are being asked to learn various subjects in school. We would like to recommend some low-cost strategies rooted in science that can help teachers reveal this information to students. These strategies take very little time and no additional investment in programs or materials.

In the field of student motivation and engagement, there are a variety of definitions, conceptualizations, and theoretical frameworks. We’ve found that the expectancy-value framework of academic motivation is particularly useful in answering the “Why do I have to learn this?” question. This framework, developed by Jacquelynne S. Eccles and Allan Wigfield (2020), provides the basis for easily implemented evidence-based strategies that can improve student motivation. When educators use instructional practices rooted in this framework while teaching a particular content area, students have higher achievement and continue to be motivated to learn more about that area in the future.

Valuing of academic content

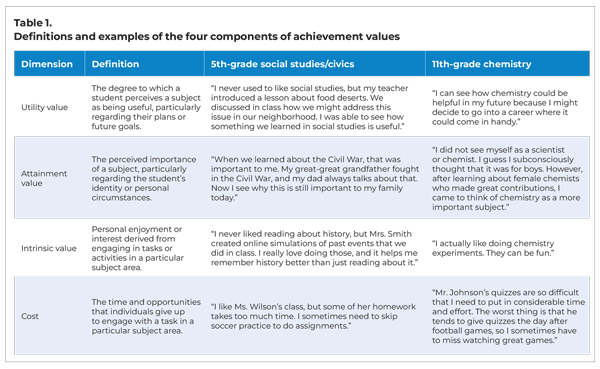

Our focus is on students’ achievement values. In academic motivation, “value” refers to students’ beliefs about whether and why certain content matters. Understanding the four different dimensions of achievement values (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000) can help us motivate all our students:

- Utility value refers to students’ perceptions of the usefulness of the content that they are learning.

- Attainment value refers to the extent to which students perceive the topic as personally important.

- Intrinsic value refers to how much students like or enjoy learning about the topic.

- Cost refers to the perceived extent to which it is worthwhile to spend time doing academic work on the topic (e.g., studying, doing homework, paying attention in class).

Table 1 provides an overview of these four dimensions, along with some examples of what two hypothetical students who strongly hold each of these beliefs might say about two subject areas.

Why is it important for students to value content?

One obvious reason educators want their students to value their academic content is because it’s more pleasant (and much easier) to teach a group of students who value what they are learning. In addition, as many educators can attest, student misbehavior tends to be lower when students are motivated and engaged (Anderman, 2021).

But in addition to these practical reasons, research clearly indicates that when students value a particular academic subject, they are more likely to take additional coursework in that area in the future when studying that subject area is optional (Durik, Vida, & Eccles, 2006; Wang et al., 2017). Moreover, students’ valuing of an academic subject is a predictor of whether they eventually enter careers in that area (Lauermann, Tsai, & Eccles, 2017; Watt et al., 2012). Consequently, if we, as educators, can cultivate a sense of passion and value for academic subjects among our students, we can enhance students’ immediate engagement and performance in those subjects, help pave the way for their future academic and career choices, and improve their achievement.

Can educators influence students’ achievement values?

The value our students place on various academic subject areas is not arbitrary. Their beliefs develop over time. The development of values in science, for instance, is influenced by many factors throughout childhood and adolescence. Some of these factors include their parents’ and friends’ attitudes toward science, their prior experiences with science in or out of school, and the messages they hear and see about science in the media.

Teachers’ instructional practices are one of the most powerful ways to influence students’ achievement values.

Fortunately, teachers’ instructional practices are one of the most powerful ways to influence students’ achievement values. In recent years, research has demonstrated that certain instructional practices can help students develop positive achievement values, even in subject areas that students previously found irrelevant and boring.

In one study (Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009), high school students were randomly assigned to one of two writing conditions. Students in the relevance writing condition were instructed to write about how what they were learning in a specific class could connect to their own lives. Students in the comparison writing condition wrote a summary of what they were learning but were not asked to connect the content to their own lives. Students in both groups wrote every three to four weeks starting at the beginning of the semester, producing an average of four to seven essays throughout the semester. In examining the effects of the intervention on students who reported low expectancies for success at the beginning of the semester, the students in the relevance condition improved by nearly two-thirds of a letter grade, compared to the students in the comparison condition. In addition, they also reported more interest in science at the end of the semester, which significantly predicted their interest in future science-related courses and careers. The results of this and other studies (e.g., Gaspard et al., 2015) demonstrate that helping students see the personal relevance of academic topics can enhance their valuing of those topics.

Strategies to enhance students’ valuing of academic content

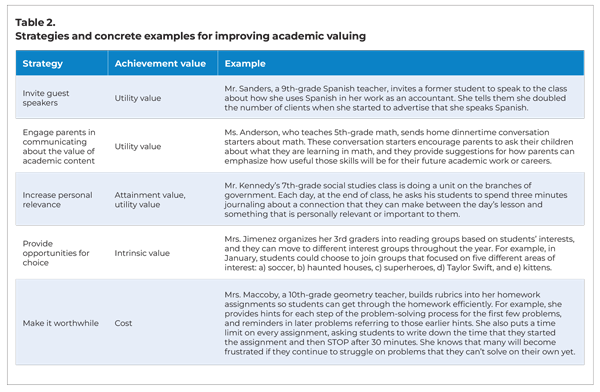

Educators can choose from a variety of strategies to enhance students’ valuing of academic content. These strategies can be adapted and used in most classes and at most grade levels (see Table 2 for concrete examples). Using a mix of these strategies throughout the year can potentially strike a spark of motivation in a student who previously thought a subject was boring and irrelevant.

Invite guest speakers

When students actually can hear about the value of a subject they are studying from someone who is using some of that information in their profession, their valuing of that content can be enhanced. Guests can participate through online meeting platforms or in-person visits to the classroom.

Engage parents in communicating about the value of academic content

Discuss with parents the value of topics you are teaching and suggest some ways that parents can engage in informal conversations about the value of studying a particular topic (Bachman et al., 2022). For example, Judith M. Harackiewicz and her fellow researchers conducted a field study (2012) in which they mailed information to the parents of high school students on the value of studying science, technology, engineering, and math topics. Parents received brochures and links to a website about the importance of science and mathematics in various careers, as well as the relevance of these subjects to everyday activities. The brochure also included suggestions for how parents could talk to their children about the relevance of science and mathematics. The researchers assessed whether the parents had used the brochures via open-ended questions on a survey; they assessed website usage by tracking log-ins. Students who received messages from their parents regarding the usefulness of mathematics and science took, on average, nearly one semester more of mathematics and science courses in the last two years of high school, compared to a control group. In addition, the students’ parents reported increased valuing of math and science for their children.

Increase personal relevance

Ask students to write a few paragraphs about the relevance of a particular lesson or topic to their own lives. Brigitte Maria Brisson and her colleagues (2017) tested this strategy in their study of a 90-minute intervention designed to influence 9th-grade students’ beliefs about the relevance of mathematics. Students were randomly assigned to three different groups: a quotation group, a text group, and a waiting control group. Students in the quotation group read six quotes by young adults, describing real-life situations in which mathematics was useful to them. Then, the students evaluated the relevance of these quotations to their own lives by responding to a set of questions (e.g., Rank how important you personally find the quotations from least to most important … and explain your ranking in detail). Students in the text group made a list of arguments about the personal relevance of mathematics to their current and future lives, and they wrote essays explaining their arguments. Students in these two groups then participated in two brief reinforcement activities after the intervention. One week after the intervention, students summarized what they remembered from their writing assignments in class. Then the following week, students repeated the writing activities. Students in the waiting control group completed the same questionnaires at the same time points as experimental groups, but they did not receive any intervention. Compared with the control group, students in both intervention groups reported greater utility value. Students in the quotation group also reported higher attainment value and interest in mathematics.

Provide opportunities for choice

Rather than giving out a single mandated assignment, allow students to choose from among several different assignments, readings, or activities. For example, instructional practices in the teaching of reading that allow students to make choices about tasks and reading materials have been shown to promote students’ reading motivation (Wigfield et al., 2004).

Make it worthwhile

We all value our time, and our students are no different. Our students engage in many other activities outside of school and have many interests and responsibilities (e.g., playing on a sports team, being with friends, doing chores, caring for siblings, and working at part-time jobs). Students will be more likely to engage with academic tasks (e.g., homework assignments) if they see the tasks as worthwhile and if they believe that working on the task is worth the investment of their time (Muenks et al., 2023).

It’s unrealistic to think that we can improve students’ valuing of content in each of the four dimensions of achievement values in every lesson or unit. Yet because the four achievement values are interconnected, using an instructional strategy that promotes one achievement value can indirectly help students develop positive achievement values in some of the other dimensions. For example, by using instructional strategies that are focused on the utility value of social studies or chemistry, teachers may also be facilitating students’ interest in those topics and lowering the perceived costs associated with doing assignments.

Enhancing motivation

Few educators want to teach a group of students who are not interested in the content or who have no sense of how or why the content might be useful. We have provided some research-based strategies aimed at enhancing students’ valuing of academic content. These strategies for the most part can be implemented with minimal additional work for the teacher and at no additional financial cost to schools.

When we can enhance our students’ valuing of a topic, we increase the likelihood that our students will take additional coursework on that topic in the future and consider (and maybe even pursue) professions that draw from or focus on that topic (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020). And by increasing student motivation, we can help make learning more enjoyable for both teachers and students.

References

Anderman, E.M. (2021). Sparking student motivation: The power of teachers to rekindle a love for learning. Corwin.

Bachman, H.F., Allen, E.C., Anderman, E.M., Boone, B.J., Capretta, T.J., Cunningham, P.D., . . . & Zyromski, B. (2022). Texting: A simple path to building trust. Phi Delta Kappan, 103 (7), 18-22.

Brisson, B.M., Dicke, A.-L., Gaspard, H., Häfner, I., Flunger, B., Nagengast, B., & Trautwein, U. (2017). Short intervention, sustained effects: Promoting students’ math competence beliefs, effort, and achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 54 (6), 1048-1078.

Durik, A.M., Vida, M., & Eccles, J.S. (2006). Task values and ability beliefs as predictors of high school literacy choices: A developmental analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98 (2), 382-393.

Eccles, J.S. & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61.

Gaspard, H., Dicke, A.-L., Flunger, B., Brisson, B.M., Häfner, I., Nagengast, B., & Trautwein, U. (2015). Fostering adolescents’ value beliefs for mathematics with a relevance intervention in the classroom. Developmental Psychology, 51 (9), 1226.

Harackiewicz, J.M., Rozek, C.S., Hulleman, C.S., & Hyde, J.S. (2012). Helping parents to motivate adolescents in mathematics and science: An experimental test of a utility-value intervention. Psychological Science, 23 (8), 899-906.

Hulleman, C.S. & Harackiewicz, J.M. (2009). Promoting interest and performance in high school science classes. Science, 326 (5958), 1410-1412.

Lauermann, F., Tsai, Y.-M., & Eccles, J.S. (2017). Math-related career aspirations and choices within Eccles et al.’s expectancy–value theory of achievement-related behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 53 (8), 1540-1559.

Muenks, K., Miller, J.E., Schuetze, B.A., & Whittaker, T.A. (2023). Is cost separate from or part of subjective task value? An empirical examination of expectancy-value versus expectancy-value-cost perspectives. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 72, 1-15.

Wang, M.-T., Chow, A., Degol, J.L., & Eccles, J.S. (2017). Does everyone’s motivational beliefs about physical science decline in secondary school? Heterogeneity of adolescents’ achievement motivation trajectories in physics and chemistry. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46 (8), 1821-1838.

Watt, H.M.G., Shapka, J.D., Morris, Z.A., Durik, A.M., Keating, D.P., & Eccles, J.S. (2012). Gendered motivational processes affecting high school mathematics participation, educational aspirations, and career plans: A comparison of samples from Australia, Canada, and the United States. Developmental Psychology, 48 (6), 1594-1611.

Wigfield, A. & Eccles, J.S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 (1), 68-81.

Wigfield, A., Guthrie, J. T., Tonks, S., & Perencevich, K. C. (2004). Children’s motivation for reading: Domain specificity and instructional influences. Journal of Educational Research, 97 (6), 299-310.

This article appears in the February 2024 issue of Kappan, Vol. 105, No. 5, p. 8-12.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Eric M. Anderman

Eric M. Anderman is a professor of educational psychology at The Ohio State University. He is the author of Classroom Motivation: Linking Research to Teacher Practice (3rd ed., Routledge, 2021).

Yue Sheng

YUE SHENG is a graduate research associate in the College of Education and Human Ecology at The Ohio State University.

Wonjoon Cha

WONJOON CHA is a graduate research associate in the College of Education and Human Ecology at The Ohio State University.