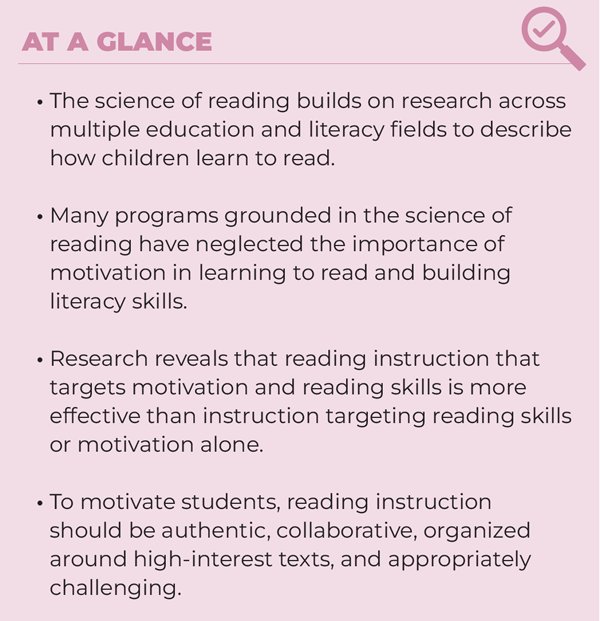

A strong research base exists for the importance of motivation in learning, but that research is too often neglected in science of reading programs.

Ms. Rodriguez gets her 1st graders’ attention and gives directions on transitioning to reading. The students drag their feet as they make their way to their desks, heads hanging. As the teacher begins guiding the students through the routine of tapping their fingers for each phoneme (sound) in CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant) words, students’ attention visibly wanes. Felix gets wiggly, Sarina stares out the window as she taps, and Malik taps on his neighbor’s arm to annoy her.

Ms. Rodriguez knows that her students are not motivated during this reading block. Nearly half her students don’t need this instruction because they have solid phonemic knowledge. All her teacher tricks to maximize motivation fail to engage the students because they are sick of the routine or bored of lessons they already know. Nonetheless, her school system requires that she teach the new structured “science of reading” curriculum to fidelity. Ms. Rodriguez wonders what scientific research says about motivation.

Understanding the science of reading

The science of reading (SOR) is a body of knowledge about how children learn to read that has been accumulated through replicated research from a broad range of disciplines (education, developmental psychology, cognitive psychology, linguistics, neuroscience, and more). This research fills volumes upon volumes of scholarly journals, academic books, white papers, research syntheses, and reports. Understandably, policy makers, education leaders, and teachers are interested in what this knowledge base says about teaching children to read. Reading, after all, is a foundational skill that is a prerequisite for educational advancement.

Three specific models — the five pillars, the reading rope, and the simple view of reading — form the foundation for the current science of reading movement, which has resulted in new policies, curricula, and practices in elementary schools throughout the U.S. and abroad.

The five pillars emerged nearly 25 years ago, when the U.S. Congress charged a group of literacy scholars, who became known as the National Reading Panel (2000), with synthesizing existing reading research to identify the most promising practices for teaching children to read. The group found strong evidence for teaching five components (pillars) of learning to read:

- Phonemic awareness: Awareness and manipulation of the smallest units of sound.

- Phonics: Knowledge of letter-sound relationships.

- Fluency: Automatic and accurate word recognition and reading with expression.

- Vocabulary: Knowledge of word meanings.

- Comprehension: Constructing understanding from text.

Around the same time, Hollis Scarborough (2001) presented the reading rope, which illustrates how word recognition and language comprehension intertwine to lead to skilled reading. Scarborough’s rope is grounded in the simple view of reading (Hoover & Gough, 1990), which suggests that reading is the combination of word recognition and language comprehension.

These models have been criticized for oversimplifying what is one of the most complex tasks we ask of elementary students (Catts, 2018) and for omitting certain instructional practices, such as independent reading (Krashen, 2005). In addition, we believe these models, and the current instructional practices rising from them, fail to consider the importance of motivation.

What’s missing?

As literacy educators and scholars, we see firsthand how the SOR movement is manifesting in schools: in policy, in curricula, in popular media, in professional development, in academic journals, in educational magazines, in newspapers, and more. Throughout it all, we have noticed that discussion of motivation is palpably missing. This absence is surprising because the importance of motivation in teaching reading has a strong scientific research base (Schiefele et al., 2012). Jessica Toste and colleagues (2020) analyzed the research into the relationship between motivation and reading and concluded, “Although most researchers agree that motivation influences student performance, models of reading development generally fail to consider motivation or other social-emotional processes” (p. 442).

Phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension need to be explicitly taught and practiced. However, if we teach these components of reading without regard for motivation, we are undermining our efforts at supporting students’ literacy learning.

To be clear, we support the fundamentals of the science of reading. Phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension need to be explicitly taught and practiced. However, if we teach these components of reading without regard for motivation, we are undermining our efforts at supporting students’ literacy learning. This is true both in the short term (as students engage in avoidant behaviors or begrudgingly complete assigned tasks) and in the long run (as students receive the message that reading is a boring activity that you must suffer through).

The power of motivation

Motivation refers to the processes of initiating and sustaining behavior (Linnenbrick-Garcia & Patall, 2015). For decades, educators and educational researchers have known about the central role of motivation in learning. When people are unmotivated, they are unlikely to continue participating in an activity. Motivation, clearly, has important implications for school, teaching, and learning. In fact, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that motivation is associated with persistence, success, and well-being (Howard et al., 2021). Reading researchers, too, have demonstrated the important role of motivation in reading outcomes (Schiefele et al., 2012; Toste et al., 2020).

Scientific research has explored what types of instruction promote student motivation. For example, The Voice of Evidence in Reading Research (McCardle & Chhabra, 2004) aimed at supporting teachers in implementing scientifically based reading research outlined in the National Reading Panel report. In this book, John Guthrie and Nicole Humenick (2004) identify four components of reading instruction strongly associated with motivation in the research literature: choice, collaboration, interesting texts, and sustained learning.

Although the relationship between reading motivation and reading competence with younger children remains underexamined, a growing body of research demonstrates that motivation plays a vital role in supporting children’s budding capacities for reading. For example, Paul Morgan and Douglas Fuchs (2007) reviewed 15 studies examining the relationship between young children’s reading motivation and reading skills and concluded that a bidirectional relationship is likely to exist between the two, a result upheld more recently by Jessica Toste and colleagues (2020). Current research shows whole-class reading programs that intentionally target young children’s reading motivation and foundational skills better enhance both motivation and skills than programs solely targeting foundational skills (Vaknin-Nusbaum & Tuckwiller, 2023). Therefore, we — like other reading scholars (e.g., Duke & Cartwright, 2021) — advocate for reading approaches that intentionally support children’s motivation to read alongside their foundational skills.

Snapshots of reading instruction today

In the tidal wave of new programs and instructional approaches fueled by an attempt to mandate the science of reading, motivation appears to be absent. Instead, mind-numbingly boring packaged programs with scripted instruction have once again turned creative and charismatic teachers into technicians who must follow programs to fidelity. And many of these programs consist of whole-class instruction without differentiation, leaving many children without the kind of instruction that will best meet their needs and maintain their interest in reading.

Both of us have experienced this problem firsthand as parents. Seth’s elementary-age daughter, Anna, entered kindergarten with strong alphabetic and phonetic knowledge. A year later in 1st grade, she was required to sit through 45 minutes of whole-class phonics instruction every day. Even as an avid reader, she quickly came to detest language arts time. Gabi, Joy’s eight-year-old daughter, had a similar experience in a different region of the country. Gabi also entered kindergarten as a proficient reader, yet she was still required to participate in scripted phonemic awareness and phonics instruction through 2nd grade.

We have also consoled preservice teachers who, after observing and delivering mandated scripted phonics and phonemic awareness programs in primary classrooms (and seeing students’ reactions to them), are questioning whether to complete their teaching degrees. Even before they sign their first teaching contract, these aspiring teachers perceive that their instruction will be stifled, their creativity undermined, and their knowledge of how best to support children doubted. Many seasoned teachers are also leaving the field in part because of the ways they are being forced to teach reading (Gomez, 2022).

So, if we return to Guthrie and Humenick’s (2004) research findings on motivation and reflect on these examples, do we see choice being leveraged to support motivation? No. Do we see collaboration being used to support motivation? No. Do we see ample opportunities for sustained learning? No. Do we see children engaging with high-interest texts? No. We find this blatant omission of well-established findings baffling because the evidence is overwhelming: When it comes to learning to read well, motivation matters.

Infusing motivation into SOR

We sincerely believe instruction should be guided by rigorous, replicated research. Phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension all contribute to learning to read. But explicit teaching of basic skills does not have to mean rote, boring whole-class instruction. Thoughtful teachers can use their knowledge of the science of reading to design motivating literacy instruction. In short, if we are truly going to follow scientific research, then motivation must be part of the equation.

Explicit teaching of basic skills does not have to mean rote, boring whole-class instruction. Thoughtful teachers can use their knowledge of the science of reading to design motivating literacy instruction.

It is possible to embed principles of motivation into instruction built on the science of reading. Specifically, reading and writing instruction that is authentic, collaborative, organized around high-interest texts, and appropriately challenging have a clear basis in the scientific literature on supporting reading motivation (Gambrell et al., 2011; Guthrie & Humenick, 2004).

Authenticity

Literacy activities that are authentic — i.e., relevant to students’ lives — are motivating (Parsons et al., 2015). A growing body of research demonstrates the importance of embedding instruction in authentic texts and for authentic purposes. For example, a study of 2nd-grade students reading and writing science texts found that student comprehension and writing did not improve with explicit teaching unless it was accompanied by authentic purposes for reading and writing (Purcell-Gates, Duke, & Martineau, 2007). Meanwhile, most activities associated with the science of reading that we see are inauthentic — that is, they are detached from students’ lives or interests (Wyse & Bradbury, 2022).

During the pandemic, Joy promoted authentic learning as she supported a small group of five-year-old children in furthering their literacy skills through a series of student-selected inquiry projects. Projects were grounded in the children’s own questions:

- How do caterpillars change into butterflies?

- What was life like when dinosaurs roamed the planet?

- How do volcanoes explode?

Systematic and explicit instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, comprehension, and writing were integrated into each project. However, they were integrated in meaningful ways that complemented each inquiry. For example, in addition to assembling high-quality informational text sets to support children’s learning, Joy created her own books for the children to read that used key vocabulary and the phonics patterns being studied. The children often referred back to the teacher-created decodable texts when making their own authentic products (e.g., a caterpillar to butterfly life-cycle play, a dinosaur ABC book).

We recognize that busy teachers may not have time to create a large number of decodable books (and this effort is certainly not required to offer children authentic reading experiences). Alternatively, alone or with the support of a reading coach or specialist, teachers can compose short pieces of writing (e.g., morning message, poem, song, or chant) with students that include targeted phonics patterns and are rooted in students’ own interests or goals.

Collaboration

Students are motivated to learn when they work together on reading and writing activities (Barber & Klauda, 2020). In Joy’s studies of young children’s motivation in reading intervention programs, for example, young readers repeatedly expressed their desire to read with their peers, and several children reported that their low motivation stems primarily from the absence of opportunities to read with friends (Erickson, 2023). One suggestion that children offered for making reading more collaborative was taking turns reading favorite books with a trusted peer. Another method for engaging young children in joyful collaborative reading experiences is with readers theater; short scripts enable children to practice foundational reading skills (e.g., decoding, fluency) together and for an authentic purpose.

High-interest texts

Many young students in Joy’s studies (e.g., Erickson, 2019, 2023; Erickson, Condie, & Wharton-McDonald, 2020; Erickson, Davison, & Markmann, 2023) have expressed concerns about the books they are required to read at school — especially in reading intervention programs. Children in kindergarten through 2nd grade have reported wanting to spend more time reading books they find personally meaningful — i.e., more authentic. Young students across these studies have expressed desires to read books centered on short- and/or long-term goals (e.g., to learn more about caring for a pet, to learn how to become a park ranger); in a preferred genre (e.g., nonfiction), and/or about a specific topic (e.g., Pokémon). One bilingual child requested to practice reading bilingual books so that he might experience the joy of reading with his Spanish-speaking mother. In short, students want to read high-interest texts that matter to them, and research has shown that they stay engaged when reading these texts, even if they’re difficult (Fulmer et al., 2015). Put another way, the integration of high-interest texts in school reading programs supports key goals from reading science and motivation science.

Appropriate challenge

Making sure reading-related tasks are appropriately challenging is another principle of motivation that should inform science of reading instruction. Reading activities that pose a moderate amount of challenge — that do not challenge children too little or too much — motivate students and encourage them to persevere (Stutz, Schaffner, & Schiefele, 2016). Therefore, differentiation in reading instruction and reading tasks is crucial to ensure students at different ability levels have assignments that meet their challenge needs.

A center-based approach to literacy instruction where students go to a thoughtfully planned center that incorporates their individual strengths and needs is one method for offering students the right amount of challenge. Having multiple adults (e.g., classroom teacher, reading coach, paraprofessional, parent) to support center work is ideal. However, we recognize that many teachers are on their own during reading instruction. In this case, offering children clear directions and practice with intentionally designed activities that include self-correcting materials is crucial to the success of a center-based approach. Centers permit the teacher to deliver differentiated direct instruction in reading foundational skills and concepts to one or more small groups of children each day while ensuring an appropriate amount of challenge. Children who are not working directly with the teacher at any given time should also be engaged in targeted, appropriately challenging work that they can complete on their own and/or with their group members because it was selected or designed with children’s individual strengths and needs in mind.

Motivation in SOR

Using the results of repeated rigorous research to guide instruction is wise. However, in implementing policy and mandating instruction based upon this research, we must use all the research available. This includes research on motivation.

Consider the following activity that can support students’ foundational reading skills and their motivation to read: A group of children who are currently working on the same phonics patterns write an article or blog post for the school newspaper on a topic they have been researching. The teacher provides explicit small-group instruction on the phonics and morphology of words used in the concepts students are studying and that they might wish to include in their article. When the children begin drafting, they likely will require additional teacher help to navigate organizational (e.g., dividing up the work) and social (e.g., appreciating the views of others) challenges. However, the ingredients of this authentic task make good use of reading and motivation science.

Motivation to read has a robust research base and has provided clear guidance for motivating students. Likewise, this knowledge base has demonstrated the repercussions of boredom, avoidance behaviors, non-participation, disinterest, and other results among students who lack motivation to read, all of which are harmful for students’ success in reading. The current science of reading initiative also focuses instructional attention on vital components of literacy instruction. However, it tends to overlook the research on motivation.

We hope that arming teachers with knowledge about the science of reading and principles of reading motivation will give them the tools to design instruction that engages students and gives them the skills they need to be proficient readers. Mandating restrictive reading instruction that disregards the expansive research on reading motivation is doomed to fail to accomplish the goal of teaching all students to be effective readers.

References

Barber, A.T. & Klauda, S.L. (2020). How reading motivation and engagement enable reading achievement: Policy implications. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 7 (1), 27-34.

Catts, H.W. (2018). The simple view of reading: Advancements and false impressions. Remedial and Special Education, 39 (5), 317-323.

Duke, N.K. & Cartwright, K. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56 (S1), S25-S44.

Erickson, J.D. (2019). Primary readers’ perceptions of a camp guided reading intervention: A qualitative case study of motivation and engagement. Reading & Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Difficulties, 35 (4), 354-373.

Erickson, J.D. (2023). Young children’s perceptions of a reading intervention: A longitudinal case study of motivation and engagement. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 39 (2), 120-136.

Erickson, J.D., Condie, C., & Wharton-McDonald, R. (2020). Harnessing the power of young children’s perceptions to support motivation. The Reading Teacher, 73 (6), 777-787.

Erickson, J.D., Davison, K.E., & Markmann, S. (2023). Toward more motivationally-supportive reading interventions: Learning from young DLLs’ perceptions of English-only programmes. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 0 (0).

Fulmer, S.M., D’Mello, S.K., Strain, A., & Graesser, A.C. (2015). Interest-based text preference moderates the effect of text difficulty on engagement and learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 98-110.

Gambrell, L.B., Hughes, E.M., Calvert, L., Malloy, J.A., & Igo, B.L. (2011). Authentic reading, writing, and discussion: An exploratory study of a pen pal project. The Elementary School Journal, 112, 234-258.

Gomez, D. (2022, October 12). Stress is pushing many teachers out of the profession. Forbes.

Guthrie, J.T. & Humenick, N.M. (2004). Motivating students to read: Evidence for classroom practices that increase reading motivation and achievement. In P. McCardle & V. Chhabra (Eds.), The voice of evidence in reading research (pp. 329-354). Paul H. Brookes.

Hoover, W. & Gough, P. (1990). The simple view of reading. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2, 127-160.

Howard, J.L., Bureau, J., Guay, F., Chong, J.X.Y., & Ryan, R.M. (2021). Student motivation and associated outcomes: A meta-analysis from self-determination theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 16 (6), 1300-1323.

Krashen, S. (2005). Is in-school free reading good for children? Why the National Reading Panel Report is (still) wrong. Phi Delta Kappan, 86 (6), 444-447.

Linnenbrick-Garcia, L. & Patall, E.A. (2016). Motivation. In L. Corno & E.M. Anderman (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (3rd ed., pp. 91-103). Routledge.

McCardle, P. & Chhabra, V. (Eds.). (2004). The voice of evidence in reading research. Paul H. Brookes.

Morgan, P.L. & Fuchs, D. (2007). Is there a bidirectional relationship between children’s reading skills and reading motivation? Exceptional Children, 73 (2), 165-183.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Parsons, S., Malloy, J., Parsons, A., & Burrowbridge, S. (2015). Students’ engagement in literacy tasks. The Reading Teacher, 69 (2), 223-231.

Purcell-Gates, V., Duke, N.K., & Martineau, J.A. (2007). Learning to read and write genre-specific texts: Roles of authentic experience and explicit teaching. Reading Research Quarterly, 42 (1), 8-45.

Scarborough, H.S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. Neuman, & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of research in early literacy (pp. 97-110). Guilford.

Schiefele, U., Schaffner, E., Möller, J., & Wigfield, A. (2012). Dimensions of reading motivation and their relation to reading behavior and competence. Reading Research Quarterly, 47 (4), 427-463.

Stutz, F., Schaffner, E., & Schiefele, U. (2016). Relations among reading motivation, reading amount, and reading comprehension in the early elementary grades. Learning and Individual Differences, 45, 101-113.

Toste, J.R., Didion, L., Peng, P., Filderman, M.J., & McClelland, A.M. (2020). A meta-analytic review of the relations between motivation and reading achievement for K-12 students. Review of Educational Research, 90 (3), 420-456.

Vaknin-Nusbaum, V. & Tuckwiller, E.D. (2023). Reading motivation, well-being, and reading achievement in second grade students. Journal of Research in Reading, 46, 64-85.

Wyse, D. & Bradbury, A. (2022). Reading wars or reading reconciliation? A critical examination of robust research evidence, curriculum policy and teachers’ practices for teaching phonics and reading. Review of Education, 10, e3314.

This article appears in the February 2024 issue of Kappan, Vol. 105, No. 5, pp. 32-36.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Seth A. Parsons

SETH A. PARSONS is a professor in the Sturtevant Center for Literacy at George Mason University, Fairfax, VA. He is the co-author of Accelerating Learning Recovery for All Students: Core Principles for Getting Literacy Growth Back on Track and Principles for Effective Literacy Instruction .

Joy Dangora Erickson

JOY DANGORA ERICKSON is an assistant professor in the School of Education at Endicott College, Beverly, MA. She is the author of Reading Motivation: A Guide to Understanding and Supporting Children’s Willingness to Read .