Centralized governance, a focus on safety protocols, and additional staffing funds all play a role in keeping European schools open.

By Anthony LaMesa

Almost unique among countries in the developed world, the United States has failed to reopen all of its schools – with the exception of some rural and Sun Belt communities. Nearly 50 percent of U.S. children are still “attending” remote-only schools.

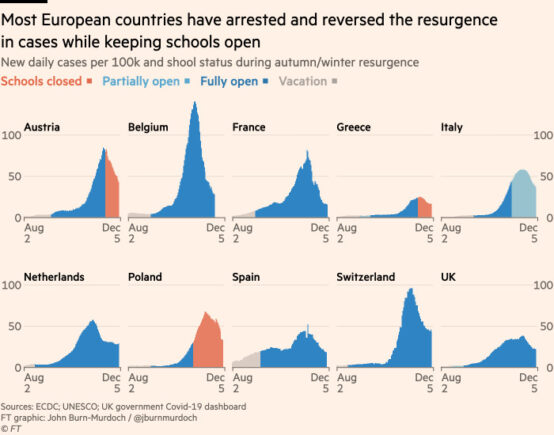

At the same time, the consequences of extended school closures for the well-being of children and their learning are increasingly clear, and European nations appear more confident than ever that they made the right choice to reopen schools with relative normalcy this fall.

Why has Europe been more successful at reopening schools safely than the United States? What can education leaders and K-12 journalists learn from the European experience?

To be sure, extreme messaging from the Trump and Biden campaigns didn’t help. President Donald Trump threatened to slash funding to school districts unwilling to immediately reopen their schools. President-elect Joe Biden’s campaign shared tweets and video advertisements in September suggesting it would be unsafe for U.S. children to return to classrooms, months after European countries like Denmark, France, and the Netherlands had already safely reopened their schools.

However, based on what I’ve seen and read about the European experience, there have been three key aspects of particular importance for getting a majority of European children back into classrooms this fall: more centralized governance over schools, stronger relationships between teachers unions and government agencies, and an ability to provide additional funds to keep schools staffed.

With additional funds for staffing to cope with absences related to illness or quarantine, it’s likely many U.S. school districts could reopen their doors to students in the new year.

With additional funds for staffing to cope with absences related to illness or quarantine, it’s likely many U.S. school districts could reopen their doors to students in the new year.

It’s helpful to begin looking at the reopening question by considering the governance of European school systems. Public school governance is highly consolidated at the national level in France or at the regional/state level in Germany, Italy, and Spain – whereas the United States doesn’t just devolve school governance to its 50 states, but to more than 13,500 school districts controlled by local school boards and cities.

In the European school governance context, it was possible for national governments to directly engage in iterative processes of negotiation to reopen schools – resulting in detailed national protocols – while, in the United States, despite the head of state demanding schools reopen on Twitter, there was effectively very little he or the federal government could do to force schools to reopen or even set the rules for doing so.

A process involving a national government and 20 regions in Italy – or another major European country – is far simpler than one involving a federal government, state governments, and thousands – 977 in California alone! – of independent school districts.

The centralization of school oversight in European countries has an obvious effect on negotiations with teachers unions over school safety plans. Unions reluctant to return their members to classrooms for safety reasons are likely to find more success negotiating with a mayor or school board than a powerful national or state government.

Their safety demands may also be different. Perhaps because European unions have to confront national and regional politicians committed to keeping schools open when they are dissatisfied with conditions in schools – and both English and German unions have recently done so – they are more likely to make measured demands of government “pushing for safety measures rather than closures,” as the Washington Post’s Michael Birnbaum recently noted.

In Europe, many union members vocally supported a return to in-person learning in countries as diverse as Sweden and Italy, a country where summer and fall union-backed protests focused on improving conditions in schools rather, than demanding they never reopen or close.

In Europe, teachers unions are more likely to make measured demands of government “pushing for safety measures rather than closures,” as the Washington Post’s Michael Birnbaum recently noted.

More centralized governance of schools not only greased the tracks of European union negotiations but has also frequently allowed governments there to more efficiently address perhaps the biggest obstacle to reopening schools – adequate staffing.

In the U.S., half of 217 school districts in 30 states surveyed by Reuters have recently reported staffing challenges. With school districts mostly dependent on local funding from property taxes, and state budgets decimated by the economic fallout of the pandemic, surging funding during a crisis is incredibly hard and a polarized federal government has been unable to deliver necessary support in order to ensure adequate staffing for what unions – and many parents – would consider to be “safe” school reopenings.

By comparison, one of the main reopening strategies that European nations have used is to provide massive infusions of funds to hire new short- and long-term teachers in order to reduce class sizes and temporarily replace medically vulnerable teachers unable to safely return to their classrooms.

Italy’s national government, for example, budgeted for the recruitment of tens of thousands of new teachers. Spain’s large Madrid region planned to hire 10,610 temporary teachers.

Following a nationwide strike on Nov. 10 over deteriorating conditions in French schools – classroom crowding exacerbated by teachers absent due to illness or quarantine – France’s national government committed to temporarily hiring 6,000 new primary school teachers and 8,000 new assistants for secondary schools until the February holidays.

The United Kingdom – having already boosted education spending by £2.6 billion this year – recently launched a “short-term Covid workforce fund” in order to support “the government’s national priority of keeping education settings open.” Schools will “be eligible if they are experiencing a short-term teacher absence rate at or over 20 percent, or a lower long-term teacher absence rate at or above 10 percent.” The UK government hasn’t revealed the fund’s expected size, but has promised “all valid claims” will be paid to eligible schools whose existing financial reserves have been close to exhausted. Eligibility will be backdated to Nov. 1 in order to help schools struggling before its launch.

While teachers unions across Europe may nevertheless be dissatisfied with national government responses, these examples reveal how centralized education systems can more nimbly respond to major needs in order to keep schools functioning during an unprecedented pandemic.

More centralized governance of schools not only greased the tracks of European union negotiations but has also frequently allowed governments there to more efficiently address perhaps the biggest obstacle to reopening schools – adequate staffing.

Here in the U.S., there have been some attempts to address school reopening in a more centralized, state-led way.

Led by its governor, Rhode Island has pursued a more “centralized” approach to reopening schools – requiring its 36 districts to conform to a single academic calendar and receive state approval of reopening plans – and, despite strong unions, has been more successful at reopening its schools than many other states.

However, Georgia, a right-to-work state, features several large districts that remain almost entirely closed, including metro Atlanta’s DeKalb County and City Schools of Decatur districts. Georgia’s governor endorsed reopening schools but delegated the entire process to local districts.

President-elect Biden has repeatedly said that the U.S. will need to spend nearly $200 billion to safely reopen schools, citing an estimate by the School Superintendents Association (AASA) and the Association of Educational Service Agencies.

While it’s difficult to identify exactly how much various European countries have spent to reopen their schools, this past summer Italy budgeted about €1 billion ($1.2 billion) for staffing and new desks. Adjusted for the population of the United States, that would be about $6.5 billion in new spending. The UK government boasts of having added £2.6 billion ($3.5 billion) to its education budget this year, which would be equivalent to the U.S. spending about $17.2 billion.

In Germany, where school funding significantly varies by state under its federal system, most schools are ventilating by opening windows and schools in the capital city of Berlin are only conducting minimal testing of students.

It goes without saying that additional funding is necessary for many U.S. communities to safely reopen their schools, but it’s also clear that much of Europe is spending less money to reopen its schools than many Americans likely imagine.

Additional funding is necessary for many U.S. communities to safely reopen their schools, but it’s also clear that much of Europe is spending less money to reopen its schools than many Americans likely imagine.

As parental confidence in U.S. public schools appears to decline and children continue to suffer increased abuse and learning loss from extended remote learning, the sociopolitical consequences of extended U.S. school closures are only going to increase.

If Europe’s recent experiences navigating unions and staffing challenges offer a single lesson for American policy makers it may be that coordinated and centralized action – isolated as much as possible from partisan politics – is necessary to succeed at reopening schools in the context of a major public health crisis.

Previous commentary:

Negative COVID coverage and prolonged school shutdowns

What makes school reopening so challenging to cover?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Anthony LaMesa

Anthony LaMesa is a freelance education consultant on both domestic and international education issues. He has worked as a Phoenix elementary school teacher; taught English and coordinated programs at NGOs in Guatemala and Mexico; and consulted for the World Bank and UNICEF. You can follow him at @ajlamesa.