With the Common Core, for the first time, education policy is playing out on social media as much as it is in statehouses and school board meetings.

After the turbulence of the test-based accountability era of the 2000s, for a moment the next wave of education reform looked like relatively smooth sailing. In 2010, the Common Core State Standards were adopted with overwhelming bipartisan support in 45 states and the District of Columbia. But, a scant three years later, storm clouds began rumbling. Beginning in 2013, polls showed public approval of the Common Core declining and partisanship increasing. Eventually, two states that had adopted the standards backed away from them (Indiana and Oklahoma). We are now in the midst of a Category 5 political hurricane (McGuinn, 2015). What factors contributed to this change in fortunes, and what does this say about the way that contemporary politics can influence education policy?

From a policy perspective, the Common Core is just the latest incarnation of the strategy that uses standards to leverage educational improvement. In many ways, the Core is a response to a series of lessons policy makers learned about the weaknesses of state-based standards reform efforts of the 1990s (McDonnell & Weatherford, 2013). In that era, each state developed its own standards and assessment systems, which led to uneven quality and rigor of state educational systems across the country (Hamilton, Stecher, & Yuan, 2008). As a consequence, the state governors and chief state school officers sponsored the development of a set of common standards. Informed by international comparisons and contemporary research on how children learn, the Common Core is different than previous incarnations of standards in that it asks educators to focus on fewer topics but more deeply in mathematics, and on more complex, content-rich fiction and nonfiction in English language arts with higher levels of cognitive demand. Two assessment consortia — The Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers and the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium — were formed to create assessments aligned with the standards.

Very few of the reasons cited for Common Core opposition had to do with the standards themselves but rather were related to other education issues that the standards have come to represent.

From a political perspective, the Common Core has come to represent a range of politically charged education issues. Sparked by the Obama administration’s decision to encourage their adoption in the Race to the Top funding competition and to provide the financing for the two testing consortia, the Common Core has raised questions about the federal role in education policy. Additionally, the Common Core has spurred debates about data privacy, the role of private enterprise in public education, and the outsized role of testing. Interestingly, none of these issues are related to the standards themselves.

The maelstrom surrounding the Common Core represents a new, deeper, and more combustible dynamic in the formulation of education policy.

But the maelstrom surrounding the Common Core also represents a new, deeper, and more combustible dynamic in the formulation of education policy. Although public discussions of education reform are part of America’s rich democratic history, their spillover into the broader cultural debates being waged on social media is unprecedented. While it may seem that social media and the Internet have been ever present, consider that the last major federal education policy initiative, No Child Left Behind, was rolled out just three years after Google’s founding. Even more remarkable is that NCLB was enacted three years before Facebook was first liked; four years before the first YouTube video, and five years before the first tweet on Twitter. For the first time, education policy is playing out on social media as much as it is in statehouses and school board meetings.

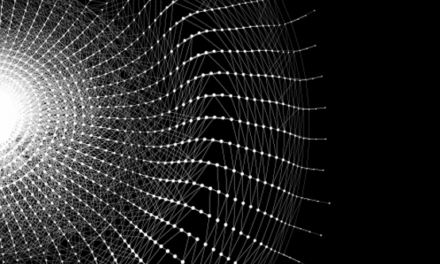

To examine the Common Core debate on Twitter, my colleagues Alan Daly from the University of California San Diego and Miguel Del Fresno from UNED (National University of Distance Education) in Madrid, Spain, collected almost 190,000 tweets from 53,000 distinct actors using the Twitter hashtag #commoncore for six months from September 2013 thru February 2014. This period covered the key time when national support for the Common Core was declining and partisanship was rising.

The goal of the #commoncore project was to flip the research process by making our findings more timely and accessible to broader audiences on the Internet in order to spark conversation before sharing them with our academic peers through the longer journal submission process. To this end, our methods and results are reported on a multimedia web site: www.hashtagcommoncore.com (Supovitz, Daly, & Del Fresno, 2015). The site unfolds like a story, looking first at the large social network of Twitter conversation around the Common Core, then focusing on the most influential actors in the debate and digging deeper into their subcommunities, language, and motivations. The site is replete with dynamic social network clouds, interactive ego networks, illustrative graphics, infographics, and podcasts with key players. The site received a tremendous response: Almost 4,000 people visited in the first two weeks, and, to date, it has had over 12,000 views. In addition, the site garnered much attention on both professional and social media and became the focus of discussion and debate in advocacy organization meeting rooms, policy circles, and research centers.

Making the invisible visible

We used a social network approach to analyze the Twitter data. Twitter is essentially a gigantic invisible multidimensional social network with individuals connected to each other through followership and reciprocal relationships. As a social network, Twitter data are perfectly suited for social network analysis (SNA). SNA makes the invisible networks of relationships visible by mapping the individuals in a particular network, including the volume, directionality, and content of their messages. In our SNA, we accessed publicly available data from Twitter and drew maps that connected Twitter users based on their patterns of tweeting using #commoncore.

In our analyses, we specified three distinct types of actors in the social networks:

- Transmitters — those who sent a large volume of tweets using #commoncore; this is called outdegree;

- Transceivers — those who had a large number of their tweets retweeted by others and were mentioned in a large number of tweets by others about #commoncore; this is called indegree; and

- Transcenders — those who had both high outdegree and high indegree.

These different measures allowed us to identify different types of influencers in the #commoncore network. We then filtered the top 0.25% of the transmitter and transceiver networks to reveal the most highly active, or elite, individuals who were over two standard deviations above the mean in their Twitter activity.

To analyze the content of the tweets of the top transmitters and transceivers, we drew a random sample of 4,500 tweets from these two groups. This sample was coded by a team of researchers using several coding schemes, after establishing 80% inter-rater reliability in the application of the codes. Tweets were coded for their overall content (information, opinions), as well as references to education topics (teacher evaluation, testing, curriculum), policy and political topics (political figures, related reforms), language, and system level (local, state, national).

Subcommunities #commoncore

While we don’t have the space here to cover all of the findings, we will describe a few of the key results. First, we found that the #commoncore network is a remarkably persistent and active network of public discourse around this major education reform in the U.S. While many topics tend to trend and quickly disperse on Twitter, the #commoncore debate is a persistent and active network. Over the past 18 months, right up to the present, there have been between 35,000 and 40,000 tweets with this hashtag each month.

Second, the social network perspective revealed three distinct structural subcommunities whose behavioral choices (i.e. choosing to follow each other on Twitter) affiliated them together. One group comprised Common Core supporters; a second group comprised individuals and groups largely from inside education (education professionals, practitioners, advocacy group members) who opposed the Common Core. The third and largest group of high influence actors was made up of individuals and groups from outside education who opposed the Common Core. The issues that spurred this group were generally unrelated to the standards themselves.

The Common Core is really a proxy war about broader cultural disagreements over the future direction of American education.

This finding is related to a third major takeaway in which coding of the tweets revealed that the Common Core is really a proxy war about broader cultural disagreements over the future direction of American education. Very few of the reasons cited for Common Core opposition had to do with the standards themselves but rather were related to other education issues that the standards have come to represent, including:

- Opposition to a federal role in education;

- A belief that the Common Core is a gateway for access to data on children that can be used for exploitive purposes rather than building knowledge to inform educational improvement;

- A source for the proliferation of counterproductive educational testing;

- A way for business interests to exploit public education for private gain, and;

- A belief that an emphasis on standards distracts from the deeper underlying causes of low educational performance, including poverty and social inequity.

Our analyses surfaced only two criticisms directly related to the Common Core standards themselves, and these were relatively rarely voiced:

- Claims that the standards are developmentally inappropriate because they were backmapped from college- and career-ready outcomes to early childhood expectations and

- Critiques that the Common Core focused solely on academic skills and expectations while ignoring equally important social and emotional development.

Differing views, different languages

By digging deeper into the language of the tweets themselves, we conducted a more granular analysis of a stratified random sample of tweets of the most prolific actors. We coded tweets based on two rhetorical approaches. One approach, which we dubbed “policyspeak,” employed more rational, analytical language that appealed to the intellect. The other approach, which we called “politicalspeak,” used more visceral, emotional language that stirred sentiments and spoke to more elemental instincts. We found that supporters of the Common Core were significantly more likely to use policyspeak, while opponents were more likely to employ politicalspeak. This was one of our most controversial findings, but we think these strategic choices likely represented tactical approaches to appeal to different audiences.

Takeaways

We draw three major lessons from this investigation.

#1. These analyses remind us that we live in an increasingly interconnected social world in which our understandings are derived from a complex set of interdependent social processes and where the diffusion of ideas, beliefs, and opinions are stretched across individuals and levels in an interrelated system.

#2. Media has evolved over the last half century — first from a passive system dominated by a few central opinion makers, then to a splintered proliferation of more partisan media outlets that allowed people to avoid information that diverged from their worldview. Now we are entering a more active phase of social media in which we are the media — where individuals are not just the consumers of media but the producers and perpetuators of what is news and dominant opinion.

#3. This study shines light on how social media networks are changing the dynamics of the political environment in which public policy is formulated. A new “activist public” of social media entrepreneurs are now jockeying with more traditional advocacy groups for attention in the political space in which policy ideas incubate and public opinion emerges.

All three of these are new phenomena that continue to rapidly change as new technologies influence the ways in which we learn, communicate, and interact.

References

Hamilton, L., Stecher, B., & Yuan, K. (2008). Standards-based reform in the United States: History, research, and future directions (No. RP-1384). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Education.

McDonnell, L.M. & Weatherford, M.S. (2013). Evidence use and the Common Core State Standards movement: From problem definition to policy adoption. American Journal of Education, 120 (1), 1-25.

McGuinn, P. (2015). Core confusion: A practitioner’s guide to understanding its complicated politics. In J.A. Supovitz & J.P. Spillane (Eds.), Challenging standards: Navigating conflict and building capacity in the era of the Common Core. Washington, DC: Rowman-Littlefield.

Supovitz, J.A., Daly, A., & del Fresno, M. (2015, Feb. 23). #CommonCore: How social media is changing the politics of education. www.hashtagcommoncore.com

Citation: Supovitz, J. (2015). Twitter gets favorited in the education debate. Phi Delta Kappan, 97 (1), 20-24.

R&D appears in each issue of Kappan with the assistance of the Deans Alliance, which is composed of the deans of the education schools/colleges at the following universities: George Washington University, Harvard University, Michigan State University, Northwestern University, Stanford University, Teachers College Columbia University, University of California, Berkeley, University of California, Los Angeles, University of Colorado, University of Michigan, University of Pennsylvania, and University of Wisconsin.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jonathan Supovitz

JONATHAN SUPOVITZ is a professor of policy and leadership in the Graduate School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania and codirector of the Consortium for Policy Research in Education, Philadelphia, Pa.