Recognizing that local coverage was reinforcing racist stereotypes, North Carolina A&T student journalists pressured news outlets to reconsider newsroom practices.

By Alexis Wray

In 2018, I was the editor-in-chief of The A&T Register, the on-campus student newspaper for the largest historically Black university in the nation, North Carolina A&T State University.

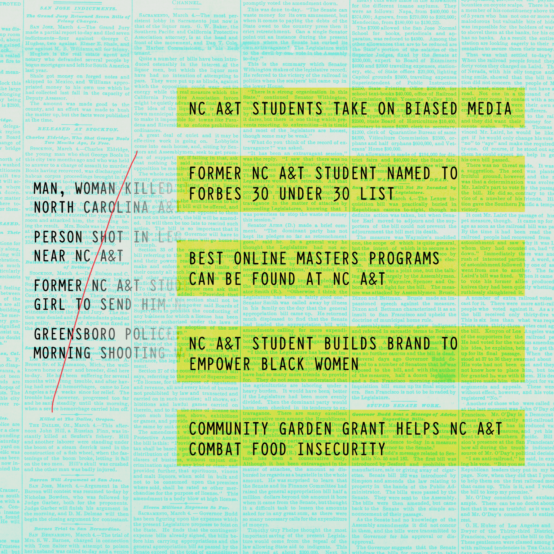

Frustrated by the consistent lack of Black perspectives in the media, for nine months during 2018 and 2019, I led a group of fellow students through an in-depth dive of local news reporting coming out of Greensboro, identifying the ways outlets covered our school. Our data confirmed what we’d suspected: That media outlets were using the university as a locator for crime in East Greensboro even though those crimes rarely—if ever—had anything to do with the campus, students, or faculty.

By associating the proximity of the university to crime and the students with criminal acts, local media outlets had long been misinforming Greensboro residents about the safety of NC A&T, elevating white supremacist tropes that have shaped media and public opinion since America’s birth, resulting in coverage that is harmful and threatening to the Black existence.

I saw our investigation as a way we could change how the media portrays the “Black Narrative,” a narrative that has been erased, mistold, and distorted for far too long. Our goal was to take control of our own stories and speak life into the narratives we did identify with by holding journalists accountable for misrepresenting the Black experience.

This optimism I had—that we as student reporters might be able to change the way professional journalists worked—led our newspaper into a year-long project supported by The Poynter Institute. Elissa Yancey, former Poynter College Media Project leader and journalist, guided our efforts by teaching our staff the importance of intentionality in storytelling.

It soon became clear to me and my staff that local reporters were, intentionally or not, inserting their own unconscious bias and beliefs about our university and the greater Black experience into their stories.

“We don’t intentionally as journalists set out to do something bad,” Yancey said at the 2019 North Carolina College Media Association Conference and awards during a panel discussion I moderated called How Beliefs Shape Coverage of News and Oftentimes Distort the Black Narrative.

“It is our job as journalists to be intentional about what we are doing. It is our job to make sure what we are doing is intentionally representative, thoughtful, and accurate.”

We identified harmful headlines that fell into two categories, each of which directly connected NC A&T to unaffiliated crime: one connection was location-based, the other based on outdated affiliations.

Here are a few examples:

- Person shot in leg at convenience store near NC A&T

- Man, woman killed in shooting near North Carolina A&T State University campus

- Greensboro police: Man killed in Sunday morning shooting was a former NC A&T student

- Former NC A&T student accused of forcing girl to send him nude photos

By associating the proximity of the university to crime and the students with criminal acts, local media outlets had long been misinforming Greensboro residents about the safety of NC A&T, elevating white supremacist tropes that have shaped media and public opinion since America’s birth, resulting in coverage that is harmful and threatening to the Black existence.

The closer I looked, the more I saw how these misleading headlines were likely to impact NC A&T’s reputation and put me and my peers at risk. They fit the definition of “subtle prejudice,“ which is often abetted by differential media portrayals of “nonwhites” versus whites, as well as de facto segregation in housing, education, and occupations, as outlined in Measuring Racial Discrimination, a panel on methods for assessing discrimination from the National Academies’ Committee on National Statistics.

HBCUs are overwhelmingly successful institutions, established to give educational opportunities to Black students who have historically been denied the ability to pursue higher education elsewhere. Because these institutions have often been built in Black communities, it felt clear to me that this biased coverage from local media outlets was a threat to the success of Black students in higher learning institutions and the Black communities who support them.

We found media distorting and falsely representing HBCU narratives throughout the country, too:

- 1 killed in double shooting blocks away from Howard University

- 3 injured in shooting near NCCU campus, Durham police say

- High Point University Comes To The Rescue Of Bennett College

North Carolina journalist Zila Sanchez, my former managing editor who also worked on the project, contends that how the university is covered plays a part in creating a dangerous reputation of an institution surrounded by crime.

The fallout is consequential: Justifications for more Black and brown students stopped by the police; local residents hesitating to support, partner with, or even attend the school; and overall community disinterest and disinvestment.

“I suspect the lack of range in coverage is due to an unknowing ignorance and unwillingness of the reporters to learn about the ongoings of NC A&T,” Sanchez said.

The result is a student body that’s made to feel criminal simply for existing. That’s not a media landscape I wanted to join.

As a journalist, I want to report in a way that preserves the reality of history and pushes society forward.

Once I understood that this coverage was built on cognitive bias (at best, in our most generous analysis) or racist tropes (at worst), I realized my role in this project had to change from investigator to problem-solver and solution-maker.

I reached out to six local media outlets to discuss our findings.

Media representatives from four of the outlets we identified—the News & Record, Carolina Peacemaker, The Rhino Times and WFMY News 2—agreed to come to campus for a roundtable discussion on April 12, 2019.

The discussion

Getting this meeting wasn’t easy.

I emailed many of the media professionals eight different times before finally deciding to call their phones, and when that didn’t work, I showed up at their offices.

Many times, I nearly gave up on the project and convinced myself that what I was doing was a waste of time. But on the day of the discussion, in efforts to have a productive and powerful conversation around race, journalism, and intentionality, I put my frustrations to the side.

I began the discussion by sharing results from an NC A&T student survey that showed the majority of students believed that news consumption is “quite likely” to play a part in how they view the world.

This came as no surprise to the media outlets, of course. They knew about their power.

We hoped they’d change how they used it.

Surveyed students also made suggestions on how local media outlets could do a better job of covering NC A&T, which included a call for more stories about students’ academic achievements and their hard work. After reviewing the student responses, I passed a small basket with folded strips of paper, each with a problematic headline, around the room. Each media representative drew one.

The News & Record‘s assistant local content director, Jennifer Fernandez, recognized the negative headline. She offered to make recommendations to her colleagues about the coverage and suggested that the staff of the News & Record could start verifying and clarifying the status of students with the university and not simply rely on law enforcement’s claim of a connection to the school.

Other representatives remained adamant that their headlines weren’t creating false narratives, and agreed amongst themselves that their use of NC A&T as a locator for crime in East Greensboro was logical and justifiable—as rooted in their work as the unexamined bias that guided their reporting.

An editor from WFMY News 2 expressed the ease and convenience of using the school’s short abbreviation in headlines. Fernadez and John Hammer of The Rhino Times added that using NC A&T as a locator was something that they have always done.

After hearing their honest responses, Emily Harris, faculty advisor of The A&T Register, suggested that the outlets could just as easily use nearby US Highway 29 as their locator for East Greensboro.

Silence fell over the room.

Very few news outlets were excited about my persistence to implement an intentional and collaborative storytelling plan. Their lack of interest in taking our suggestions to improve biased coverage surprised me.

I was certain we wouldn’t see a change in their headlines.

Coverage today

Despite their responses at the roundtable, Greensboro news outlets did seem to find new ways to frame crime stories in their headlines:

- 1 injured in shooting Saturday in Greensboro

- Woman, man killed in shooting near NC university campus

- College freshman from Raleigh is shot and killed in Greensboro, police say

Our follow-up research found that locations in East Greensboro that were previously used in headlines as “near NC A&T” were now shaped in a way that didn’t harm or affect the integrity of the university or the students.

Todd Simmions, associate vice chancellor for NC A&T University Relations, had persistently engaged the media and questioned their coverage, elevating the work of The A&T Register after that initial meeting.

Journalists have a huge responsibility to be factual, honest, and ethical, but often the media outlets for which they work operate in environments of habit, not imagination. And that habit is often racist.

“There are layers to racism, and you have to apply just as much intentionality around undoing the effects of that racism as [the work that] went into creating the environment where that racism exists,” Simmions said.

Journalists have a huge responsibility to be factual, honest, and ethical, but often the media outlets for which they work operate in environments of habit, not imagination. And that habit is often racist.

I reached back out to the four media outlets who participated in the discussion to see how they felt their coverage has changed.

The News & Record, Carolina Peacemaker and WFMY News 2 have all shown interest in the student-led approach of covering NC A&T by not at all or occasionally using the university as a locator—especially in relation to crime stories.

Fernandez, of the News & Record, has taken a new approach to writing or editing crime stories; she now uses streets rather than landmarks as locators.

“Just because we’ve always done something a certain way doesn’t mean we can’t reassess our processes to see where we might be able to improve them,” said Fernandez.

We made a change, and for that, I’m proud of my colleagues. But more change must come for this industry to move away from biased coverage.

Journalists have a huge responsibility to be factual, honest, and ethical, but often the media outlets for which they work operate in environments of habit, not imagination. And that habit is often racist.

Why, for instance, are we reporting on these crimes daily while not reporting on criminal offenses of the powerful against these communities?

What if corporate crime made the nightly news as often as violence did?

What if a story of student success led the 6 o’clock broadcast?

The A&T Register staff. Photo courtesy of the author.

To my fellow HBCU journalists

I felt consumed by this investigation. I couldn’t escape the nasty reality of journalists who don’t know how to cover communities of color.

This reporting deterred me from a traditional career in journalism.

I was tired of writing about the issues and decided to be a part of the change. I now use my passion for storytelling in nonprofit work, and I am able to focus on telling the people’s narrative through a new lens.

While this investigation played a huge part in what my career looks like today it is also a reminder that my work isn’t over. Biased coverage rooted in unconscious racism not only affects HBCUs but communities of color throughout the country, and I will continue to work and fight to combat false narratives.

There is power in student journalism.

As a collective of badass students who want fair representation in the media, I invite you to restore narratives and repair broken trust between journalists and communities of color.

Lead your charge, student journalists, and command a fair narrative.

This story was originally published by Scalawag, a journalism and storytelling organization that illuminates dissent, unsettles dominant narratives, pursues justice and liberation, and stands in solidarity with marginalized people and communities in the South. Republished with permission.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alexis Wray

ALEXIS D. WRAY is a storyteller, communicator, and movement journalist, she seeks to tell stories that most impact her community. Alexis believes that impactful stories create change and promote societal advancement. Her work as a freelance journalist and communications specialist has steered Alexis in the direction of intentional storytelling and accountable journalism. She strives to bring awareness of diverse topics to the South by staying active in her storytelling in the Appalachian region.