Mainstream journalists are beginning to question the toxic notion that education is the primary vehicle for social equality.

By Jon Shelton

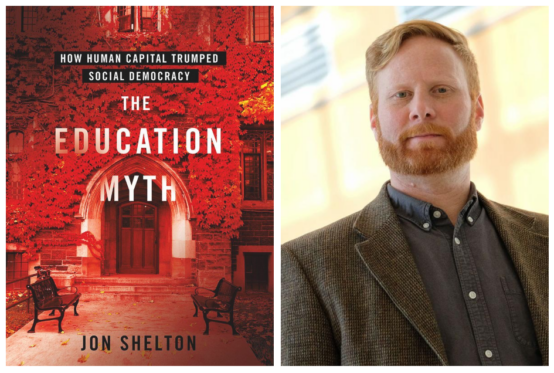

On May 8, 2023, Washington Post columnist Perry Bacon Jr. used my new book “The Education Myth: How Human Capital Trumped Social Democracy” to chart a vision for a better education system:

“America’s decades-long, bipartisan ‘education reform’ movement, defined by an obsession with test scores and by viewing education largely as a tool for getting people higher-paying jobs, is finally in decline,” argued Bacon. “What should replace it is an education system that values learning, creativity, integration, and citizenship.”

My book argues that American politicians over the past 50 years or so have overemphasized investment in education — human capital — at the expense of other important social and economic rights like the right to a job, healthcare, and housing.

That problematic idea is finally coming under attack from both the left and the right in our contemporary politics.

I don’t oppose public education — on the contrary, I believe the implications of my argument will help us to save and revivify education in our country — but my book does ask everyone to rethink what it is we have been asking our education system to do: help individual working people, as if by magic, overcome a labor market increasingly stacked against them.

Indeed, in contrast to virtually all of American history, most education reformers in the recent past have even dropped any pretense that our schools serve any other purpose.

But more and more people are questioning that logic, including the Post’s Bacon.

As the author of the book, of course, I was interested to read his piece. But I also think the piece is something of an exception that proves the rule: most high-profile centrist media outlets have done too little questioning of the education reform paradigm in the recent past.

By and large, mainstream education reporting has only questioned specific reform strategies from within the paradigm of the education myth.

My hope, however, is that more education journalists will soon, like Bacon, address the issue of overreliance on education that is detailed in my book.

My hope is that more education journalists will address the issue of overreliance on education.

As I have thought about the implications of my argument, I keep coming back to the physicist Thomas Kuhn’s notion of a paradigm shift.

A paradigm is a fundamental way of approaching the world, and, importantly, it is socially constructed. In other words, we have a collective framework for understanding the world, but that framework can change when we are presented with enough new information to destabilize our worldview. In that instance, a paradigm can change, opening the way for something new.

The paradigm we have been living in was constructed in the 1950s by Chicago school economists like Theodore Schultz and Gary Becker, who popularized the concept of human capital as the explanation for the increasingly prosperous and more equal economy that emerged after World War II (much more important, in reality, was the power of labor unions and a robust social welfare state).

We’ve been living in that world ever since as politicians, beginning with the Johnson administration, sought to alleviate poverty by focusing on the supposed deficiencies of individual working people. Never mind that most people in the 1960s who were impoverished — especially African Americans, as civil rights activists like Bayard Rustin pointed out — were in that position because they lived in cities where jobs and other social opportunities didn’t exist.

That human capital paradigm had almost completely choked off other political alternatives by 2001 and the passage of No Child Left Behind, as Democrats and Republicans competed with each other to remake our education system under the pretext that our schools needed to be held accountable to the long-term economic fortunes of American workers.

As my Wisconsin colleague Neil Kraus points out in a forthcoming book, we’ve indeed been sold a “fantasy economy” by educational reformers bent on retaining the political economic status quo at all costs.

Most major media outlets have accepted uncritically the claim that education represents the best path to economic opportunity.

Though my book isn’t really about the media’s coverage of the education myth, I do think that, for decades, most major media outlets have accepted uncritically the claim from politicians and education reformers that education represents the best, if not the only path, to economic opportunity.

Any number of pieces in the New York Times opinion page over the years could help to prove the point, but as an example, on May 2, 1983, the Times castigated President Ronald Reagan for not being taking the lead on education reform in the wake of the landmark report “A Nation at Risk.”

The report, as readers are likely aware, made the case that the American education system was in dire need of reform. It blamed growing economic insecurity in the United States — caused in actuality by corporate disinvestment in American industry and efforts to fight unions tooth and nail beginning in the 1970s — on the supposed failures of the education system.

The problem wasn’t just with the premise of the report, however. It was its outcome, which, it turns out, was built on the commission’s efforts to cherry-pick data to fit its pre-existing narrative.

The Times editorial page, however, uncritically accepted the report’s findings: “Poor schooling threatens the nation’s ability to compete in world markets and to adapt to new technology, the report says, while poor skills and illiteracy of minority groups limit their participation in national life, thereby threatening democracy.”

After citing a study that pointed to how Japanese children were outperforming American kids, the piece concluded that “Overcoming these impediments requires strong leadership. Instead of exerting it, President Reagan blames the Federal Government for harming education.”

Or witness Al Neuharth, the late founder of USA Today, on March 19, 2010, chastising President Obama’s “Race to the Top” proposal for not going far enough to ensure our education system prepared students for careers.

Obama was elected in 2008 with a mandate from a broad coalition of working people who wanted less corporate power, greater protections for American workers, and more economic rights. What they got was education reform predicated on opening new charter schools and disciplining teachers with the hope that that would magically create economic opportunity for more Americans.

But Neuharth didn’t think that was enough: “What we need is a plan that requires all high school graduates to take at least two years of college and make it financially possible for them to do so. Traditionally, we’ve provided a free public education through the 12th grade. If we’re going to keep up—or catch up—with some countries (like China) in preparing young people for careers, a 12-year education program is no longer enough.”

Now, I’m a university professor, and I agree that everyone should be able to go to college if they want to. A university education should be a right in the wealthiest country in the history of the world! But the problem is that paying for every student to go to college won’t actually alleviate the economic inequality in our country, and we certainly shouldn’t force every young person to go.

Paying for every student to go to college won’t actually alleviate the economic inequality in our country, and we certainly shouldn’t force every young person to go.

One way or another, our view of education and its potential for eliminating economic insecurity appears to be undergoing a paradigm shift.

The weight of new interpretations about our education system and what we expect it to do are in the process of destabilizing the education myth.

In addition to mine, a host of recent books have highlighted the rampant inequality and disaffection that has grown in the past few decades in the “meritocracy” we’ve been told exists.

Plenty of left-leaning social democratic media outlets — from Jacobin to the American Prospect to Jennifer Berkshire and Jack Schneider’s Have You Heard? podcast— were sympathetic to my argument from the get-go.

However, the Washington Post column and an extensive interview Inside Higher Ed published in the wake of the book launch indicates a growing mainstream interest in understanding how the media (and our political system) has badly misunderstood our education system.

Our view of education and its potential for eliminating economic insecurity appears to be undergoing a paradigm shift.

For folks reporting on what is happening, I’d like to suggest that you stop and critically examine politicians’ assumptions when they assert that student test scores are essential for their long-term economic success or suggest education and job training as the sole solution to the nation’s growing economic inequality and widespread economic security of so many working people.

How can education be the answer to these problems if educational attainment at both the high school and college level has increased at the same time as our income gap continues to get wider and fewer people can make ends meet on a day-to-day basis?

The education system most certainly has a role to play in solving these problems, but in my view, that role is more likely to be successful if it teaches our students about the real roots of economic insecurity — the growth of corporate power and anti-worker practices like the abuse of non-competition agreements, the difficulty of workers forming unions when they want to, and the policies we’ve pursued stymieing access to truly universal healthcare and good affordable housing for everyone.

Shelton is Professor and Chairperson of the Democracy and Justice Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay and author most recently of “The Education Myth: How Human Capital Trumped Social Democracy.” You can follow him at @prof_shelton.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

The Grade

Launched in 2015, The Grade is a journalist-run effort to encourage high-quality coverage of K-12 education issues.