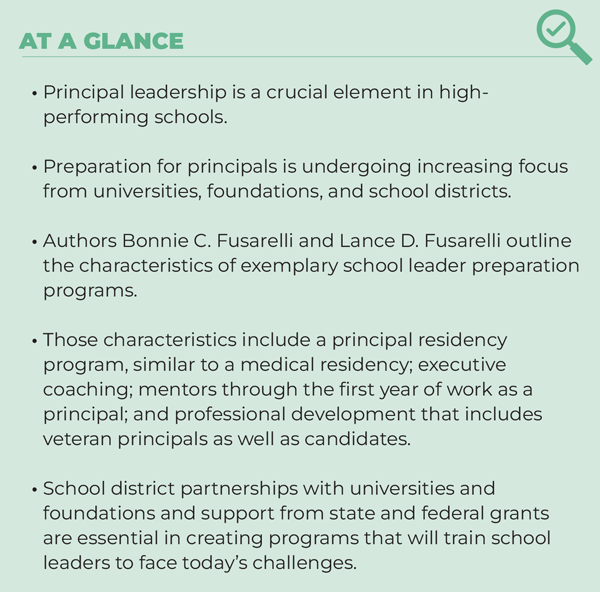

To train principals who can improve educational outcomes for all students, investment in leadership preparation is timely, necessary, and urgent.

Principal leadership is a crucial element of school performance. A landmark research review from 2004 found that principals are second only to teachers in impacting student achievement at school (Leithwood, Seashore Louis, & Wahlstrom, 2004). The Wallace Foundation commissioned a recent follow-up review of more than 200 studies, which suggested that principals’ influence on achievement may be even greater and broader than previously believed. Among other things, they influence teacher satisfaction and retention, student attendance, and rates of exclusionary discipline (Grissom, Egalite, & Lindsay, 2021). Accordingly, principal preparation has received increasing attention, and the Wallace Foundation’s University Principal Preparation Initiative and other organizations are devoting resources to identifying best practices in leadership preparation and development.

Drawing from recent reports highlighting exemplary programs and practices, we have identified several research-based best practices for improving principal preparation (Darling-Hammond et al., 2007; Education Development Center, 2023; Fusarelli, Fusarelli, & Drake, 2019; Grissom, Egalite, & Lindsay, 2021; Orr & Orphanos, 2011). State legislators, federal officials, foundations, school districts, and universities can use these findings to implement best practices nationwide.

What are some of the hallmarks of effective principal preparation programs?

Partnerships with K-12 districts to recruit strong candidates

Exemplary principal preparation programs start with school district partnerships. Together, districts and leadership preparation programs work to identify strong principal candidates among teachers and encourage them to pursue leadership opportunities. Districts build this leadership development pipeline into succession planning. Given the growing discrepancy between student and principal racial and ethnic backgrounds, exemplary programs work with district partners to identify and recruit candidates who reflect the student populations and communities they will lead (Siddiqi, Sims, & Goff, 2018). Superintendents and principals can identify and tap excellent teachers with strong leadership potential, ideally focusing on individuals who successfully work with students from historically underserved populations.

When considering candidates, exemplary programs go beyond the traditional application for admission, with a goals statement and letters of recommendation. They put candidates through experiential assessments, including role-plays, interviews, timed assessments, and video presentations based on actual school performance data. A team of faculty, retired school leaders, current district leaders and principals, and high school students then reviews candidates’ performance on these assessments. This rigorous selection helps programs identify candidates with the competencies and dispositions that research has linked to excellence in leadership. Many competencies are teachable, so candidates do not need to be highly skilled in each area, but they should have a growth mindset and be receptive to feedback.

Commonly identified competencies such as emotional intelligence and time and conflict management in current national and state leadership standards are insufficient to effectively lead in today’s schools. Effective principal preparation programs identify other essential abilities to look for, such as a sense of urgency, a focus on the whole child and community, a culturally inclusive attitude, receptivity to feedback, humility, and comfort navigating uncertainty. Determining whether candidates possess these competencies or are able to learn them requires going beyond traditional entrance metrics for university-based programs. Rigorous selection requirements linked to effective practice help ensure that candidates possess leadership potential.

Emphasis on practical learning —with a twist

Exemplary preparation programs not only engage candidates in authentic learning experiences but also expect them to learn by leading in authentic settings. For example, leadership candidates might create and deliver professional development sessions and then receive feedback on their performance, including their ability to use research to inform practice. Coursework is presented in modules that use adult learning theory, authentic experiences, and personal reflection to deepen learning. Candidates focus on practice by delving into case studies and role-playing authentic scenarios with video cameras recording the session for later reflection. Exemplary programs incorporate ideas from specialized trainings, such as Crucial Conversations/Crucial Accountability, Facilitative Leadership, conflict resolution, curriculum design/mapping, Understanding by Design, and digital learning (Fusarelli, Fusarelli, & Drake, 2019). These trainings equip aspiring leaders with the skills necessary to become successful school leaders.

In addition, excellent preparation programs provide opportunities for on-site experiences in which candidates experience and apply the learning from their coursework during the daily flow of an actual school day. Much like in a medical residency, candidates conduct learning rounds and site visits to high-performing public, charter, and private schools. These rounds expose candidates to different ways of leading and doing, encouraging them to think in new ways. An important component of learning rounds is providing opportunities to observe and learn about child, adolescent, and even adult development and about developmentally appropriate teaching and learning practices.

Another valuable on-site experience involves spending time with students. In one nationally recognized program, North Carolina State University’s Educational Leadership Academy, inspired by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe’s (2011) work and adapted from Stanford d.school’s Shadow a Student Challenge, aspiring leaders shadow preK, elementary, middle, and high school students (with parent approval) from the moment they get on the school bus to the end of their day. Observations from the shadowing experiences, as seemingly mundane as being incredibly thirsty all day, often result in more student-friendly practices, such as allowing students to have water bottles at their desks.

Effective programs also train aspiring principals in design studio processes, which enable them to frame issues through a variety of lenses and discover innovative solutions to stubborn problems. Pat Ashley, director of North Carolina State University’s Durham Principal Leadership Academy, designed a framework for evaluating potential solutions on a four-point scale: bad practice, basic practice, best practice using research-based solutions, and breakthrough practice (Fusarelli, Fusarelli, & Drake, 2019). This scale encourages leaders to push beyond the status quo and seek significant school improvement. An example breakthrough practice was the development of a microschool by a group of newly minted principals in rural, high-poverty Edgecombe County, North Carolina. The student-driven microschool, launched in 2017, gradually expanded to include all students in grades 6-12 (Zimmerman, 2020). Breakthrough practices like this require leaders to have political savvy and a commanding knowledge of policy, policy making, and advocacy.

Full-time, year-long principal residency

Full-time residency experiences permit aspiring principals to immerse themselves in schools and engage in practical, job-embedded activities under the supervision of a principal mentor. In place of a traditional internship, excellent programs provide a full-time, yearlong paid residency so candidates can develop strong interpersonal relationships, diagnose student learning needs, recognize effective teaching, model reflective practice, and master leadership skills that support school improvement efforts.

Some states, such as North Carolina, grant provisional assistant principal licenses to candidates, permitting them to engage in the real-life work of an assistant principal while supervised by a mentor principal. Near the end of their residency, candidates complete a field-based problem of practice grounded in a needs assessment of their placement school. Recent examples include using student performance data to identify deficiencies in teaching specific math concepts and creating targeted professional development to address these deficiencies, as well as efforts to incorporate more trauma-informed practices in schools. The culminating problem of practice addresses issues in their placement school, and they can use these skills once they are hired as assistant principals and principals.

Coaching and early career support

The transfer of learning from training programs into leadership practice has been shown to dramatically increase with individualized coaching: from 5-10% without coaching to 80-90% with coaching (Joyce & Showers, 2002). Matching aspiring principals with an executive coach from outside the school who provides support and mentorship in both the residency year and their first year as a school leader resolves some of the long-standing problems with typical principal mentor programs in which the mentors are senior leaders within the school or district. The supervisory nature of the typical mentoring relationship means that it may be difficult for mentees to share confidences, especially when they are struggling. New leaders benefit from having a mentor outside the employing school system whom they can go to for advice and support. These executive coaches are retired school leaders who have been recognized as exemplary in leading school improvement and are paid a small stipend for their service.

In some exceptional preparation programs, residents are paired with a principal mentor (similar to a chief resident) who advises them in the daily functions of their work during their internship. They help residents “live their learning” during their field experiences and principal residency by:

- Demonstrating effective leadership and management behaviors.

- Treating the resident as a principal in training and engaging them in teacher evaluations, staffing and scheduling, student discipline, individualized education program (IEP) meetings, and school-based budgeting.

- Communicating about the resident’s progress and providing frequent feedback and guidance in weekly meetings with the resident and biweekly meetings with the resident’s executive coach.

New principals and assistant principals also need support during their novice practice years (Browne-Ferrigno, 2004; Browne-Ferrigno & Johnson Fusarelli, 2005). Excellent preparation programs continue to provide transitional and early career support, at least through residents’ first year as a school leader and preferably through the second year, usually through an executive coach.

A promising no-cost approach to continuous engagement and development of graduates is for preparation programs to organize post-degree conferences structured like an Edcamp, in which participants set the agenda at the session, or using the Center for Leadership and Educational Equity’s Consultancy Protocol, in which participants think through dilemmas together (www.schoolreform initiative.org/download/consultancy). Post-degree convenings allow graduates to network and come up with potential solutions to challenges they are facing. By empowering graduates to identify and organize themselves around topics they deem most important, preparation programs can provide a safe sounding board for graduates to share and receive feedback on problems, root causes, and solutions.

Development of current principals

Highly effective principal preparation programs develop and support leaders with great potential. However, these promising graduates often are hired into systems where the existing principals and district leaders may lack many of the skills needed for effective school leadership. Current principals and district leaders may be constrained by the system in which they lead or lack essential skills, knowledge sets, or dispositions to dramatically improve schools and student outcomes. Some districts will even place promising aspiring leaders in a residency school whose principal is weak and needs to be propped up. This short-sighted solution is appealing to some superintendents in low-performing districts because it helps to temporarily plug holes in their leadership bench.

Exemplary preparation programs not only engage candidates in authentic learning experiences but also expect them to learn by leading in authentic settings.

Well-prepared residents often find themselves in a challenging position in that they want to implement strategies for school improvement, but they have little decision-making authority. It’s as if they are Formula 1 race cars who must operate on a go-kart track. Hence, excellent programs prepare their graduates to effectively lead from the middle. Most graduates will first serve as assistant principals. Even in high-

performing schools, a nuanced understanding of how to lead and make improvements while not being in the top seat is a career challenge most graduates face.

Innovative preparation programs have created ways to simultaneously prepare future leaders and provide professional development to current principals. For example, one program collaborated with school districts to develop a series of six daylong trainings across the academic year for both current principals and the residents in their school. The principals are exposed to the latest research-based leadership practices and can contribute their experienced perspectives. The principals earn continuing education credits, and the aspiring leaders earn university course credit. Principal/resident pairs are assigned homework that requires them to apply their learning in their school between sessions, and they receive executive coaching as needed. Such coordinated, collaborative approaches are only possible when strong university-school district partnerships are encouraged, established, and nurtured.

State, federal, and foundation support

The exemplary leadership development we’ve described requires an investment of time and resources from state or federal officials, foundations, school districts, universities, and aspiring leaders themselves. However, the cost is nominal when compared to the human resources costs involved in hiring new principals. Investing in principal preparation also may mitigate the multiple negative impacts of principal turnover, which is especially important given that “high principal churn in schools with larger populations of historically marginalized students and greater performance challenges is an important, largely unrecognized issue for educational equity” (Grissom, Egalite, & Lyndsay, 2021, p. 52).

State legislatures play a key role in funding leadership preparation. For example, state funds support the North Carolina’s Principal Fellows Program, a competitive leadership preparation grant program. The state provides funding to pay aspiring principals’ salaries during a full-time, yearlong principal residency. The school district sponsoring the resident usually covers the cost of health insurance so that they have a bit of “skin in the game” and feel a responsibility to ensure that those entering the leadership pipeline can succeed. A state-funded competitive process that requires programs to adopt certain research-based best practices sends a clear signal that leadership development is critical and going all-in is better than halfway measures. The U.S. Department of Education and private foundations also can encourage these efforts through competitive grants. In addition, foundations play a key role in facilitating and disseminating research into best practices in leadership development.

Ideally, residents who receive government or foundation funds should commit to serving a minimum period, preferably at least three years, as assistant principals and principals in high-needs schools. In doing so, highly trained graduates will use the knowledge, skills, and dispositions they gained to lead schools that most desperately need principals who have a focus on equity and excellence. To track the on-the-job performance of graduates, states can develop information systems, like the leadership dashboards created in states such as North Carolina with funding by the Wallace Foundation. These provide actionable data to universities and districts to inform continuous program improvement efforts (for examples of district efforts, see Anderson, Turnbull, & Arcaira, 2017).

Pathways and university partnerships

Universities and school districts must form genuine, collaborative partnerships to improve principal preparation and build a clear pathway from preparation to the principalship. Districts must commit to involving senior district leaders in preparation efforts, including assisting in offering specialized training. Superintendents and school boards should develop and support a district human capital management plan that includes a focus on developing, recruiting, and retaining excellent teachers and leaders. That pathway should include processes to build leadership capacity broadly by supporting teacher leadership. Public Impact’s Opportunity Culture program, for example, allows for teachers to take on different roles as part of a team. Individuals from teacher leadership programs who have clear potential and interest in becoming administrators might then be selected to participate in a leadership program that’s part of an established district-university partnership.

Strong, authentic partnerships between districts and preparation programs help ensure that the leadership program pays attention to the local district’s needs and prepares school leaders to craft and deploy breakthrough practices from Day 1. Partnering school districts and universities can work together using instruments such as the Education Commission of the States’ Quality Measures Principal Preparation Program Self-Study Toolkit to help identify gaps in preparation programs. As part of this process, university faculty need to rethink their duties, roles, and responsibilities. Building a coherent, integrated framework will require faculty to leave their silos to work in a far more collaborative manner.

Rethinking license requirements

Finally, in many states, principal license credentials are specific to building levels and grades. In today’s tight principal labor market, more flexibility is needed, especially in rural, low-performing, and hard-to-staff districts. Due in part to the proportionally larger number of elementary schools to middle and high schools, most often a principal’s first placement is at the elementary level. Therefore, excellent principal preparation programs should include field experiences across the preK-12 school levels.

Effective programs prepare leaders who have a strong working knowledge of developmentally appropriate teaching and learning from preschool through adulthood so graduates can effectively lead professional development to improve faculty and staff practices. By having experiences across school levels, graduates gain a systems perspective with a deep understanding of the importance of vertical alignment of curriculum across grades.

In the 2021 Wallace Foundation report on research into the principalship, the authors note that “it is difficult to envision an investment with a higher ceiling on its potential return than a successful effort to improve principal leadership” (Grissom, Egalite, & Lindsay, 2021, p. 3). Given abysmal National Assessment of Educational Progress scores and the massive learning loss during the COVID-19 pandemic, an investment in leadership preparation is timely, necessary, and urgent if we are to improve educational outcomes for all students.

References

Anderson, L.M., Turnbull, B.J., & Arcaira, E.R. (2017). Leader tracking systems: Turning data into information for school leadership. Policy Studies Associates.

Browne-Ferrigno, T. (2004). Principal excellence program: Developing effective school leaders through unique university-district partnership. NCPEA Education Leadership Review, 5 (2), 24-36.

Browne-Ferrigno, T. & Johnson Fusarelli, B.C. (2005). The Kentucky principalship: Model of school leadership reconfigured by ISLLC standards and reform policy implementation. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 4, 127-156.

Darling-Hammond, L., LaPointe, M., Meyerson, D., Orr, M.T., & Cohen, C. (2007). Preparing school leaders for a changing world: Lessons from exemplary leadership development programs. Stanford University, Stanford Educational Leadership Institute.

Education Development Center. (2023). Quality measures: Principal preparation program self-study toolkit (11th ed.).

Fusarelli, B.C., Fusarelli, L.D., & Drake, T.A. (2019). NC State’s principal leadership academies: Context, challenges, and promising practices. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 14 (1), 11-30.

Grissom, J.A., Egalite, A.J., & Lindsay, C.A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. The Wallace Foundation.

Joyce, B.R. & Showers, B. (2002). Student achievement through staff development. Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.

Leithwood, K., Seashore Louis, K., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How leadership influences student learning. Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement, University of Minnesota; Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto; & The Wallace Foundation.

Orr, M.T. & Orphanos, S. (2011). How graduate level preparation influences the effectiveness of school leaders: A comparison of the outcomes of exemplary and conventional leadership preparation programs for school principals. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47, 18-70.

Siddiqi, J., Sims, P.C., & Goff, A.L. (2018). Meaningful partnerships: Lessons from two innovative principal preparation programs. The Hunt Institute.

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2011). The understanding by design guide to creating high-quality units. ASCD.

Zimmerman, E. (2020, October 14). In pandemic’s wake, learning pods and microschools take root. The New York Times.

This article appears in the December 2023/January 2024 issue of Kappan, Vol. 105, No. 4, p. 8-13.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Lance D. Fusarelli

LANCE D. FUSARELLI is a professor of educational leadership and policy at North Carolina State University, Raleigh.

Bonnie C. Fusarelli

BONNIE C. FUSARELLI is a professor of educational leadership and policy at North Carolina State University, Raleigh.