My daughter Breeze is now waddling into the toddler stage, and she has picked up a disturbing new habit. She likes to rip the pages out of books.

It’s an act that sends my wife and me into hysterics. As academics, there’s something about hearing a book page shred into pieces that sends us into alarm. When we hear her tear a page from Adventures of Qai Qai or Equality’s Call, we feel like a piece of us is torn out along with it. It’s a deeply emotional feeling. It reminds me of what books — what literacy — mean to me.

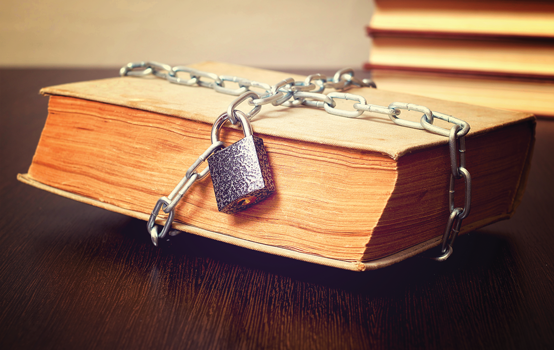

The recent national debate on book bans has raised the same kinds of feelings — and it compels me to ask questions whose answers are even more important than how best to toddler-proof a book collection. What do books mean to us? When should books be censored? How do we protect books from “the culture wars”? How do we stop the ripping of the pages?

With these questions in mind, I want to place the modern discourse within a larger history and offer a theory on whether and when book censorship could be necessary.

Let’s start with some history.

The larger story of book censorship

We find records of book censorship as far back as we can trace in the history of civilization. More often than not, these stories involve anti-democratic leaders acting to silence political opposition. In pre-Common-Era China, legend has it that Emperor Shih Huang Ti burned books and buried scholars who followed the philosopher Confucius. In first-century Rome, Emperor Caligula banned the reading of the Odyssey, in part because of its democratic ideals. For almost half of the entire second millennium, the Roman Catholic Church maintained a list of banned books. In the early 1930s, German Nazis burned thousands of books by Jews, communists, and other political and ideological dissenters. Book censorship has almost always been about maintaining political power.

The U.S. has been on a different trajectory. With free speech given a central place in the country’s governing document, America’s legal tradition has largely been to protect books, not ban them. We see this tradition surface in the 1920s, when conflict emerged in California over whether the King James Bible could be included in a school library. In Evans v. Selma Union High School District, the California State Supreme Court rejected the petition against the inclusion of the Bible, stating that “the mere act of purchasing a book to be added to a school library does not carry with it an implication of dogma.”

This decision preserved the legitimacy of books as educational tools of free speech. So, too, did the New York State Supreme Court 25 years later when it ruled against a group pushing to remove The Merchant of Venice and Oliver Twist from the New York City Secondary Schools’ approved reading list. If a book is not “maliciously written” to “promote bigoted and intolerant hatred,” the “public interest in a free and democratic society does not warrant or encourage the suppression of any book,” ruled the court in Rosenberg v. Board of Education.

We see courts’ consistent protection of books under the strength of the First Amendment in 1972 in Todd v. Rochester Community Schools, in which a Michigan court protected Slaughterhouse Five’s use in a literature course, despite disputes over the religious references in the book. We see it again in 1976 in Minarcini v. Strongsville City School District when five Ohio students objected to the inclusion of Catch-22 in the high school curriculum and school library.

In 1976, a case finally reached the U.S. Supreme Court. The local school board governing the Island Trees Union Free School District of New York had created a book review committee that recommended the board remove five books from a school library. The board agreed, stating the books were “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic and ‘just plain filthy.’” Yet, in 1982, the highest court in the land ruled in Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico that the school board had extended beyond its reach and violated the First Amendment.

This is far from an exhaustive list, but it captures the essence of the legal trend. When schools and districts ban books, they step on a rake.

Identifying the guardrails

Even though courts have largely argued that finding a book offensive is not a sufficient condition for banning, book censorship in schools has been successful when texts are considered sexually obscene; explicitly offensive to a racial or religious group; or lacking in artistic, literary, political, or scientific value.

Today, books in schools are, in a sense, judged in two ways. Is the book fostering hate speech? If so, it falls under rulings that have carved out hate speech as a loophole for restricting free speech. Second, books are judged by the Miller test, which emerged from Miller v. California — a landmark 1973 U.S. Supreme Court case that reset the parameters for obscenity.

Hate and obscenity. Those are the guardrails.

A third criteria has legally fallen by the wayside: We should be protecting books based on their potential value to American society. This is the most difficult criteria to adjudicate. How do we know if a text — or a drawing or a symbol — has societal value? It’s a question whose answer often only becomes clear long after a text is published, and the texts with the highest value sometimes invite the most criticism. The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, published in 1979, is one of the most popular novels in America. It is also one of the most controversial. Powerful texts that inspire thought, introspection, or societal critique deserve protection.

Is there value in texts we disagree with? What do we make of texts that we ideologically oppose? Should those texts be protected, too? These are the questions of our current political moment. It is important to remember that by protecting texts with opposing views, we are not endorsing those words and ideas. We are doing something far more important. We are creating room for texts that move us in meaningful ways. We are allowing for what Derek Walcott (1992) calls “the fate of poetry [which] is to fall in love with the world, despite its history.” A book could inspire unity. It could motivate political action, sometimes in reaction against the very idea the book disseminates. That reaction, though, rarely should be to ban that book in its entirety.

Understanding the nuance

“Rarely,” though, is the operative word. The criteria — hate, obscenity, and lack of value — form a tripod. The important feature of any tripod is that the legs connect to achieve balance. Book censorship works in a similar vein. Obscenity, hate, and lack of value are distinct, but they must be considered together to achieve balance.

Here are the central dilemmas of the intersection. What happens when books promote ideas that have value to people looking to enact harm? What happens when that harm extends even beyond hate speech into acts of hate? How much responsibility do we assign to books for the acts of individuals inspired by their interpretation of the text? In the American legal system, we preserve the freedom of books by blaming the bad intentions of readers, not the books themselves.

What happens in the opposite situation? What do we do when, instead of promoting books with objectionable ideas, people decide to enact harm by censoring books? What do we do when such people gain political power? This is the question of our time; it’s a question for all times. Our focus is not on keeping books from the wrong hands, but on keeping books accessible for the right hands.

Doing so is becoming more challenging by the day. According to ongoing research from PEN America, we have seen books banned in 138 school districts across 32 states since the beginning of 2021 (Friedman & Johnson, 2022). The rationale for the bans makes clear that the motivations are largely political. About two in five of banned books feature LGBTQ+ themes. It is the same ratio for books featuring people of color as protagonists. Most book bans are tied to anti-wokeness laws winding through the chambers of state legislatures. It’s not about obscenity. It’s not about harm. It’s about refusing to see the value in the perspectives of people on the margins.

My daughter rips pages out of childishness. It is quite normal for small children at this stage to explore books in this way, even if it leads to literary destruction (Akamoglu & Meadan, 2019). After all, she’s a toddler who is still learning to appreciate text. She doesn’t yet realize that ripping out pages from books means that books ultimately go away, but she’s learning.

Let’s hope America is learning, too.

References

Akamoglu, Y., & Meadan, H. (2019). Parent-implemented communication strategies during storybook reading. Journal of Early Intervention, 41 (4), 300-320.

Friedman, J. & Johnson, N.F. (2022), Banned in the USA: The growing movement to censor books. PEN America.

Walcott, D. (1992). The Antilles: Fragments of epic memory. Nobel Lecture.

This article appears in the May 2023 issue of Kappan, Vol. 104, No. 8, pp. 58-59.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jonathan E. Collins

Jonathan E. Collins is an assistant professor of political science and education and the associate director of the Columbia University Center for Educational Equity, both at the Teachers College, Columbia University, NY.