Breaking away from the one-teacher, one-classroom model enabled teachers at an Arizona elementary school to lean into their strengths and find greater professional satisfaction.

In May 2021, as many educators across the United States were digging deep into their reserves to finish the most challenging year of their professional careers, teachers at Stevenson Elementary School showed signs of excitement and boundless energy. They were advocating to expand a team-based staffing model piloted by their colleagues teaching 3rd grade. And they were ready to go big. They were not interested in growing the pilot by just another grade level. Instead, they wanted to start the 2021-22 school year with team-based staffing schoolwide.

Stevenson Elementary School is part of Mesa Public Schools (MPS), the largest school district in Arizona, serving more than 58,000 students across 82 sites. Stevenson is home to 650 kindergarten through 6th-grade students, of whom more than 80% qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. Under the leadership of Principal Krista Adams, the school had been experiencing exciting academic growth before the pandemic, and the change in school climate was palpable.

A big part of that change involved empowering educators to think differently about staffing. In fall 2020, Adams and her educators, in collaboration with district leadership and the Next Education Workforce initiative at Arizona State University (ASU), assembled a team of 3rd-grade educators, each with their own areas of expertise, who shared a common roster of students. This innovation in staffing allowed the team to deepen and personalize learning for all students and made the job of teaching more rewarding and sustainable for educators.

A workforce design problem

Recent surveys indicate that nearly 50% of educators are contemplating leaving the profession earlier than planned or within the next two years (GBAO Strategies, 2022; Merrimack College & EdWeek Research Center, 2022). In 2018, the annual PDK Poll found, for the first time in the 50-year history of the survey, that a majority of parents (54%) would not want their own children to become teachers (PDK International, 2018). In this year’s poll, only 37% of respondents said they would want their child to become a teacher (PDK International, 2022). Since 2010, teacher-preparation programs have seen, on average, declines in enrollment of more than 35% (Will, 2022). These data show that teaching is becoming a less appealing profession, and unless we act now, the staffing challenges we experienced during the last year may be the beginning of an ongoing crisis.

We must attend to the underlying reasons educators are finding the job unappealing. If we don’t, we will continue to struggle to recruit and retain great teachers, and, in turn, we will make little progress toward closing equity gaps driven, at least in part, by students’ uneven access to well-prepared and experienced educators (Darling-Hammond, 2022).

The job of teaching doesn’t have to be inflexible, isolating, and unsustainable.

One aspect of the teaching profession that we believe is worth examining is the design of the teaching workforce itself — specifically the one-teacher, one-classroom staffing model that dominates in U.S. schools. In these one-teacher, one-classroom staffing models, whether at the elementary or the secondary level, we ask educators to be all things to all students at all times. The first day on the job looks remarkably like the 3,000th day on the job, and we typically ask first-year teachers to possess the same set of knowledge and skills as we do veteran educators. To magnify this challenge, teachers are asked to take on this daunting pursuit alone. Yes, there are grade-level teams and data teams and professional learning communities, but the day-to-day work of being a classroom educator is incredibly isolating (Labaree, 2004).

The job of being a teacher also is remarkably inflexible. What happens when a professional educator calls in sick, wants to present at a conference, or needs to attend their own child’s individualized education program (IEP) meeting? Most educators go to great lengths to not miss school, even at the expense of our personal health, professional growth, and family obligations. The one-teacher, one-classroom model of staffing schools creates 3.5 million points of possible failure each day, one point for every educator who may not show up to work. This vulnerability was on sharp display during the height of the omicron surge in the winter of 2022.

The job of teaching doesn’t have to be inflexible, isolating, and unsustainable. The history of humankind has shown time and again how well people can solve problems when they’re empowered to work together (Heifetz & Linsky, 2004). During a time in our profession where teacher turnover is high, retention is low, and some positions go unfilled for years at a time, the conditions have never been more favorable to redesign the fundamental way we staff our nation’s schools.

A team-based model

The journey into team-based staffing at Stevenson Elementary began with a shift in how the school thinks about its work. Rather than ask, “Do we have enough educators to staff the school?” Stevenson started with the question, “Which educators do our students need to help them flourish?” With buy-in from teachers and families, support from district leaders, and assistance from ASU, Adams and the educators at Stevenson designed a Next Education Workforce team-based staffing model with their learners at the center.

Approaches to team-based staffing vary; however, at their core, all Next Education Workforce models include (1) teams of educators with distributed expertise sharing a common roster of students; (2) a focus on deeper and personalized learning for all students; and (3) new and better ways to enter the profession, specialize, and advance. To help school systems design and implement new staffing models, ASU offers professional learning for school- and systems-level leaders as well as cohort-based experiences for educator teams.

While all Next Education Workforce staffing models share a set of design elements, no two models are the same; the local context, students, curriculum, and educators all inform the design. Some elementary models have teams at each grade level. Others have created mixed-grade teams, sharing rosters of learners in grades 2-4, for example. Many secondary schools build interdisciplinary teams that combine educators according to their curricular focus and the students they serve.

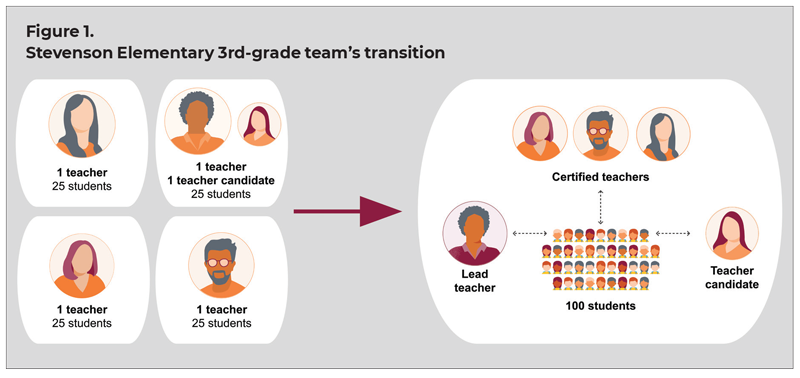

Principal Adams and the Stevenson educators were able to take the design elements and create a staffing model that met the needs of their specific school community (see Figure 1). They started with the 3rd-grade team in fall 2020 and implemented team-based models schoolwide in fall 2021.

The following were key aspects of Stevenson’s team-based staffing design:

- Distributed expertise and task shifting: Educators specialize in particular aspects of the job, such as planning for specific content areas, communication with families, and implementation of a restorative justice program. Historically, each educator was expected to be great at every aspect of teaching; now they can lean into their strengths and specialize.

- Flexible, dynamic schedules: Scheduling is flexible and fluid. While there is a daily schedule, the team has the autonomy to modify it to meet the students’ needs or to adjust if a team member is absent.

- Creation of a lead teacher position: One teacher on each team serves as team leader. The team leader continues to teach, but also is responsible for helping distribute team responsibilities, adjusting the flexible schedule, and coaching teammates. Team leaders receive additional compensation, making this role an advancement opportunity for veteran teachers who want to stay in the classroom.

- Protected team planning time: Teachers have daily planning time together and an extended two-hour block during weekly early release days. Principal Adams holds this time sacred, ensuring that teachers are not asked to participate in other school activities during this planning time.

- Sheltered roles for novice teachers: Teacher candidates and first-year teachers are both incorporated into teaching teams. They enjoy the benefit of learning from multiple professional educators, and their responsibilities can be adapted to match their level of expertise in specific aspects of the job.

The 3rd-grade team at Stevenson is housed in four interconnected classrooms, each with its own purpose: a gathering space for the entire grade, a reading hub, a math hub, and a writing hub. On most days, students engage with each of these content areas, as well as an inquiry-based innovation class rooted in science and social studies standards, led by a teacher with expertise in those areas. Both the schedule and the classroom spaces are designed to be flexible, with teacher teams extending sessions, moving furniture, or making other adjustments as needed. (See details at https://workforce.education.asu.edu/school-spotlight/stevenson-elementary-school.)

Teachers working in team-based models were getting what they wanted: They were not alone, and they were less overwhelmed.

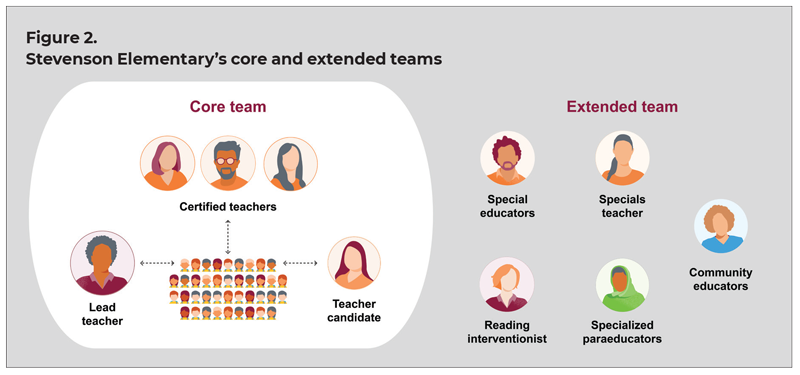

As Stevenson has expanded team-based staffing schoolwide, it has been able to strategically deploy other educators in the building as part of “extended” teams on an as-needed basis (see Figure 2). Some of these extended team members include:

- Special educators who operate as their own team and provide both push-in and pull-out services as part of an inclusion model.

- Specialized paraeducators who have received training in reading intervention and the science of reading.

- A reading interventionist who collaborates with lead teachers and supports the team of paraeducators.

- Community educators who are often members of the local community and join teams for specific units of study aligned to their expertise.

- Specials teachers who offer standalone electives (music, art, physical education) and can help integrate their areas of specialty into lessons delivered by the educator teams.

Satisfied educators at Stevenson and beyond

As the 2021-22 school year unfolded, inspiring accounts began to emerge from within the walls of Stevenson. Teachers were happier and more motivated and welcomed visitors interested in learning about what they had designed. In a year when educators were increasingly disillusioned, teachers working in team-based models were getting what they wanted: They were not alone, and they were less overwhelmed.

In the spring 2022 MPS climate survey, educators at Stevenson reported being more satisfied with the work they do, were more likely to believe they work in an environment that contributes to their job effectiveness, and had feelings of greater overall satisfaction with their working conditions than other MPS educators. Their successes, along with those from a handful of other schools in the district, prompted Mesa Superintendent Andi Fourlis to set the bold goal that at least 50% of MPS schools will implement team-based staffing models within the next two years. As the 2022-23 school year begins, more than 30 schools (about 40% of all schools) are in the process of building whole-school, team-based models.

At a system level, the district is creating new roles; reexamining educator evaluation and incentive structures; and redesigning their recruitment, hiring, and retention practices to better align with team-based staffing models and a student-centered approach. In a system that, like many others, is rooted in trying to do the same things better, this is truly an effort to do better things. MPS is not alone in this work. At least seven other districts across Arizona and California are partnering with the Next Education Workforce initiatives team at ASU to design and implement team-based staffing models. Additionally, through a partnership with AASA (The School Superintendents’ Association) and its Learning 2025 Initiative, ASU is hosting a cohort of school systems across the country interested in exploring team-based staffing models in greater detail and to help them decide if these models make sense for them.

As a society, we can continue to operate under the current paradigm of the one-teacher, one-classroom. In so doing, we will also spend valuable time and money recruiting, preparing, and trying to retain educators in a job that remains isolated, inflexible, and unsustainable — and increasingly unappealing. Although team-based staffing models will not address all the challenges facing educators and educational systems today, they create flexibility in the system and opportunities for educators to shape the jobs they actually want.

References

Darling-Hammond, L. (2022). Reimagining American education: Possible futures: The policy changes we need to get there. Phi Delta Kappan, 103 (8), 54-57.

GBAO Strategies. (2022). Poll results: Stress and burnout pose threat of educator shortages. National Education Association.

Heifetz, R.A. & Linsky, M. (2004). When leadership spells danger. Educational Leadership, 61 (7), 33-37.

Labaree, D.F. (2004). The trouble with ed schools. Yale University Press.

Merrimack College & EdWeek Research Center. (2022). First annual Merrimack College teacher survey: 2022 results. Education Week.

PDK International. (2018). The 50th Annual PDK Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward the Public Schools: Teaching: Great respect, dwindling appeal. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (1), NP1-NP24.

PDK International. (2022). The 54th Annual PDK Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward the Public Schools: Local public school ratings rise, even as the teaching profession loses ground. Phi Delta Kappan, 104 (1), 38-43.

Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publishing.

Will, M. (2022). Fewer people are getting teacher degrees. Prep programs sound the alarm. Education Week, 41 (28).

This article appears in the September 2022 issue of Kappan, Vol. 104, No. 1, pp. 33-37.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Brent W. Maddin

Brent W. Maddin is executive director of the Next Education Workforce, Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, Arizona State University, Tempe.

Randy L. Mahlerwein

Randy L. Mahlerwein is assistant superintendent of secondary 7-12, Mesa Public Schools, Mesa, AZ.