“I mean it makes you feel inadequate. Like am I saying something that’s crazy? I’ve been educated. I have a master’s. I passed all of the Massachusetts teacher exams just like everybody else. It’s frustrating you know?” — Dennis Sangister

“I and another African-American man had outdoor duty, to just kind of monitor and police the front of the building at dismissal times just to usher students away from the building and make sure there are no issues outside the building. I think it was clear and evident why we were chosen for those roles.” — George Little

Dennis Sangister, a veteran black male middle school teacher, recounted with great frustration sitting in on department meetings and having his comments about how to address the social-emotional and academic challenges facing students of color discounted by white colleagues on the faculty. For Sangister — and many of the other 26 black male participants in a recent study of black male teachers’ school-based experiences — these recurring experiences led him to believe his colleagues saw him as intellectually inferior (Bristol, 2014).

Another teacher in this study, George Little, described having to serve in more disciplinary roles when compared to his colleagues. Administrators assigned him and the other black male teachers to administrative duties such as monitoring or “policing” the school door during dismissal. Like the other black male teachers in the study, Little believed that administrators and his colleagues saw him as a behavior manager first and as a teacher second.

Combine Little’s observation with research indicating that black men have one of the highest rates of turnover in the teaching profession (Ingersoll & May, 2011; Sealey-Ruiz & Lewis, 2011), and we are left with the question of how schools and districts can better support black male teachers.

Supporting male teachers of color

The Boston Teacher Residency Male Educators of Color Network is affiliated with the Boston Teacher Residency (BTR) program. Created in 2003, BTR attracts recent college graduates, community members, and career movers. Considered a postbaccalaureate apprenticeship program, BTR trains and certifies preservice teachers who commit to teach for three years in Boston Public Schools (BPS), the country’s oldest and one of its largest urban public school systems. The district continues to be under a 1974 federal court order to end racially discriminatory hiring and student assignment practices (Morgan v. Hennigan).

Network participants were able to teach and learn from each other because they believed others in the room regarded them as intellectual peers.

Aware of the district’s racial climate around teacher hiring, the high turnover rate for male teachers of color, and the challenging school-based experiences of black male teachers, as a clinical teacher educator in BTR, I created a monthly professional development opportunity for male teachers of color by male teachers of color. The theory of action was that professional development focused on addressing the unique challenges of male teachers of color would help them develop tools and strategies to navigate their school environment. More important, these teachers would be better able to focus on creating conditions that facilitated learning for students — the majority of whom were of color and from working-class families.

The mission of the Male Teachers of Color Network in the residency program was to provide social-emotional support to male teachers of color and a space to reflect on practice in service of student learning. To accomplish this mission, I selected two graduates of the program, whose classes I had observed as a clinical teacher educator, to facilitate the sessions. The group met each month from January 2013 until May 2013 and then during the 2013-14 school year. I sent initial invitations to the 79 male teachers in the BTR pipeline (preservice and inservice) who identified as Asian, black, or Latino. We had a core group of about 15 participants.

Meeting from 5 p.m. to 7 p.m. on Fridays became an ideal time for several reasons. Many participants had school leadership positions, coordinated an extracurricular activity, or coached a sports team, after-school obligations that typically occurred between Monday and Thursday. There also appeared to be a fraternal component to the group since many of the participants had personal connection even though they didn’t work at the same school. Fridays, then, also served as opportunity for these teachers to reconnect outside of the everyday demands of teaching.

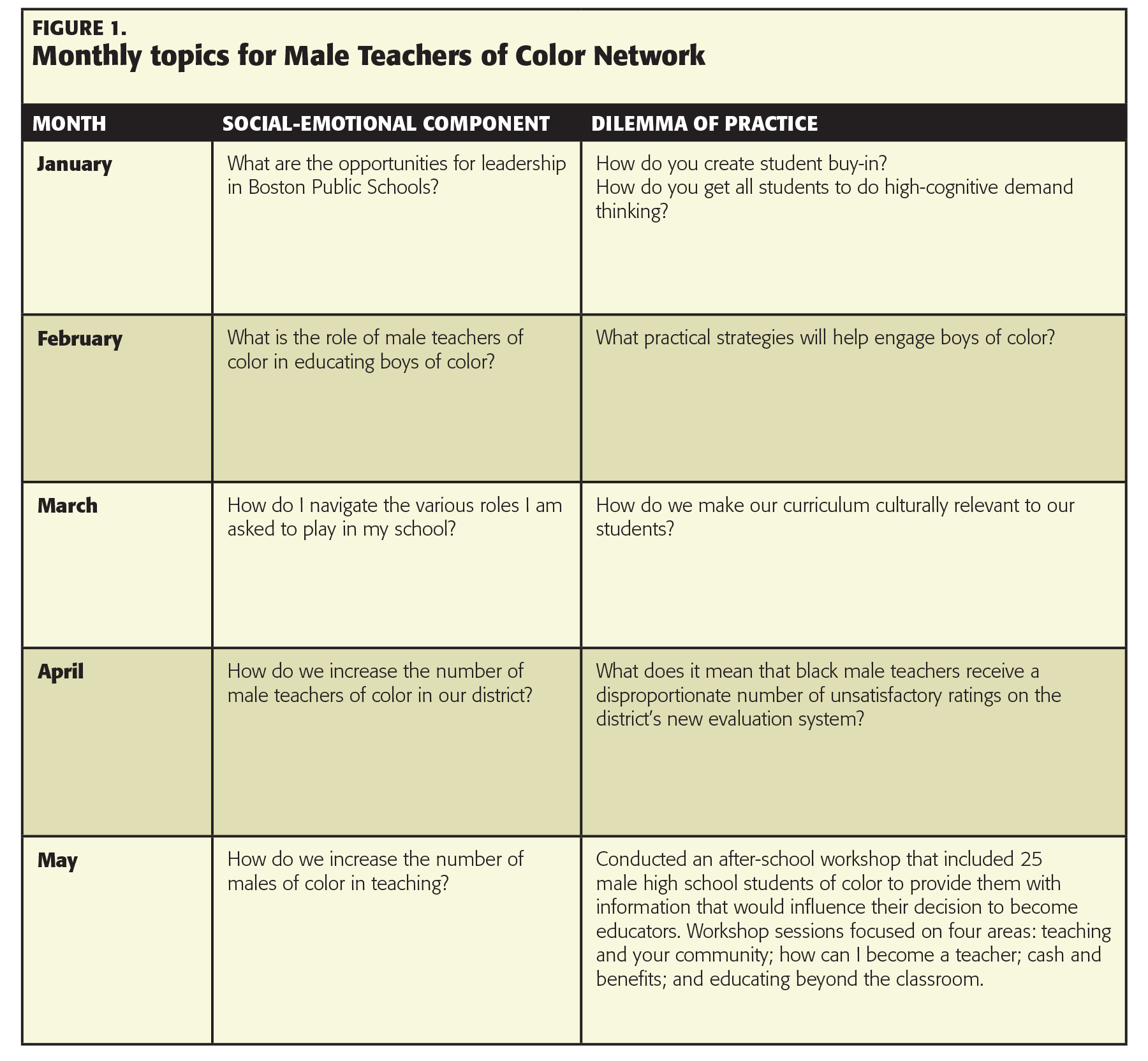

The co-facilitators and I agreed to structure monthly meetings in two purposeful ways: The first half of the meeting focused on creating conditions that would attend to the social-emotional challenges faced by participants in schools (see Figure 1). These challenges included being the only male teacher of color on the faculty, attempting to find ways to respond to the stereotypical roles colleagues asked participants to play — policing black and Latino boys, for example — or feeling ill-equipped to create an environment that would support learning for male students of color.

While it was crucial for group members to talk about their social-emotional challenges, what brought us together was the fact that we were teachers. In order to become better teachers for our students, we needed tools to continuously improve our practice (Darling-Hammond, Wilhoit, & Pittenger, 2014). As such, during the second half of the meeting, a group member presented a dilemma in his practice on which he desired feedback (see Figure 1). The presenter met with me and one of the facilitators before the meeting to decide on a focus question. Next, the presenter chose artifacts that would help the group understand his dilemma of practice. We used the Issaquah Protocol developed by the National School Reform Faculty (www.nsrfharmony.org/system/files/protocols/issaquah.pdf). Those monthly meetings occurred in the presenting teacher’s classroom.

Male teachers of color; boys of color

During the first half of the February meeting, participants discussed the role of teachers of color attempting to educate boys of color. What became immediately clear was that in their schools, participants’ colleagues turned to these male teachers of color to redress the challenges presented by boys of color. However, their teacher preparation programs had not prepared these male teachers of color for these challenges. In the safety of the network, participants could turn to each other for help.

Participants described the importance of incorporating students’ culture in the classroom as a conduit for learning and called it “valuing the cool.” For example, two participants shared how they incorporated students’ urban vernacular as a way to facilitate learning. Across urban spaces in particular, the phrase “sick with it” connotes a high degree of proficiency on a particular topic. Damion Martin, an 8th-grade English teacher, co-opted “sick with it” into his content after hearing students use the term when talking to each other. “One of the things I hear often is that students say, ‘oh he not sick with it.’ So I took the Common Core Supporting Ideas with Evidence and changed it to Supporting Ideas with Quotes,” Martin said. Martin described weaving together the language students brought into the classroom and the language students were learning in the classroom, supporting ideas with evidence.

In the safety of the network, participants could turn to each other for help.

When students discussed literary text and did not support their claims with evidence from the text, he would say, “you are not sick with it.” Then, he would point to the sign he created in front of the class “sick with it” and redirected students to provide additional evidence with quotes. Martin encouraged other teachers in the group to “listen to what students are saying, and be creative about how to mesh” students’ culture from outside the classroom to the content objectives. For Martin, this was one example of how he was valuing the cool.

Right after Martin shared how he incorporated students’ language into the classroom, George Bennett, a high school math teacher, provided an example from his class. Bennett said he used the term “math swagg” to develop students’ scholar identities. Swagg, especially across urban centers, refers to the unique traits that make one stand out from his/her peers. Having swagg epitomizes acceptance in one’s peer group. In his class, Bennett used math swagg to refer to students’ mathematical confidence. And, to display students’ swagg, Bennett titled a bulletin board Math Students Who Achieve Great Gains, or Math Swagg. On the bulletin board, he recorded students’ progress as measured by their scores on quizzes and exams.

Understanding the lesson of valuing the cool proved useful for all participants but especially the preservice and novice teachers in the group. These teachers learned how they could organize their classrooms to incorporate students’ culture.

As I studied school-based experiences of black male teachers, participants described not having their ideas about improving student outcomes valued by their colleagues. But the exact opposite was the case in conversations of those at a network group function; among the other male teachers of color, participants freely shared strategies they found to be effective in engaging students, particularly boys of color.

Culturally sustaining pedagogy

During the March meeting, James Harper shared the African-American history course he designed for high school students. Since we were in Harper’s classroom, he showed a timeline students created chronicling the experiences of African-Americans from chattel slavery to the present. Then, Harper described what he called black music Fridays when he encouraged students to bring in music from their personal collections. His only criterion was that the artist had to be of African descent.

Students listen to each song in groups, paying particular attention to its lyrics. As students listen to the lyrics, they evaluate whether the messages contribute to “uplifting blacks” or “setting blacks back for 70 years.” Harper uses the 70 years to refer to the period before the civil rights movement. Harper said many of the songs students brought in fell into the “setting blacks back for 70 years” category. As such, Harper told participants in the network that he considered himself responsible for bringing in more positive music where artists focused on uplifting blacks.

As Harper shared how he designed his curriculum to be culturally sustaining (Paris, 2012), network participants began to develop a model of how to design such curricula.

In order to become better teachers for our students, we needed tools to continuously improve our practice.

While network participants attended their own school-based and district professional development, what made the Boston Teacher Residency Male Educators of Color Network unique was the opportunity to have a space to share and receive support around a challenge they faced as a result of their racial and gender identity. Also, unlike the district and school-based professional development, network participants could bring authentic dilemmas in their practice to their peers. Finally, one of the conditions that enabled participants to teach and learn from each other was the belief that they were viewed by other individuals in the room as intellectual peers.

Significance

The monthly professional development initiative for male teachers of color in the Boston Teacher Residency pipeline provided social-emotional support to male teachers of color and a space to reflect on practice in service to student learning. In so doing, male teachers of color learned strategies to improve learning conditions for students who have historically stood on the margins and enhanced their own tool kit for navigating their work environments. There is some evidence, though anecdotal, of the positive effect on individual participants. One co-facilitator said that he had been considering leaving the profession, but this group was one of the primary reasons he decided to stay. Another preservice teacher used the word “family” to describe the other members of the group.

The Boston Teacher Residency Male Educators of Color Network has been incorporated into the Boston Public Schools’ ongoing efforts to retain male teachers of color. In March 2014, BPS launched the Male Educators of Color Executive Coaching Seminar Series, a professional development opportunity open to all male educators of color in the district. One aim for the coaching seminar series is to support and retain male teachers of color, as well as increase the number of male school and district leaders of color. Ultimately, the Boston Teacher Residency Male Educators of Color Network and the recently created Male Educators of Color Executive Coaching Seminar Series may serve as models for other school districts attempting to design professional development opportunities to support male teachers of color and, more important, to allow these teachers to improve learning outcomes for culturally and linguistically diverse students.

References

Bristol, T.J. (2014). Black men of the classroom: An exploration of how the organizational conditions, characteristics, and dynamics in schools affect black male teachers’ pathways into the profession, experiences, and retention (Unpublished dissertation). Columbia University, New York, N.Y.

Darling-Hammond, L., Wilhoit, G., & Pittenger, L. (2014). Accountability for college and career readiness: Developing a new paradigm. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 22 (86).

Ingersoll, R. & May, H. (2011). Recruitment, retention, and the minority teacher shortage. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, Consortium for Policy Research in Education and University of California Santa Cruz, Center for Educational Research in the Interest of Underserved Students.

Morgan v. Hennigan, 379 F. Supp. 410 (D.C. Mass., June 21, 1974).

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy. Educational Researcher, 41, 93-97.

Sealey-Ruiz, Y. & Lewis, C. (2011). Transforming the field of education to serve the needs of the black community: Implications for critical stakeholders. Journal of Negro Education, 80 (3), 187-193.

CITATION: Bristol, T.J. (2015). Male teachers of color take a lesson from each other. Phi Delta Kappan, 97 (2), 36-41.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Travis J. Bristol

TRAVIS J. BRISTOL is an assistant professor in the Graduate School of Education at the University of California, Berkeley.