Innovations stories give readers hope and create opportunities for change. The most effective examples are also realistic and compelling.

By Will Callan

In nearly four months of tracking innovations and progress coverage for The Grade, I’ve become used to certain recurring characteristics.

There’s the language of aspiration, often present in the headline: “School district aims to x,” “School leaders hope that y.”

There are the stories that rely entirely on administrators, lawmakers, and press releases, which tend to paint a picture rosier (and less interesting) than reality — and often fail to show anything in action.

And then there are the pieces shorn of context, which present the featured program — a career-technical program for aerospace hopefuls, a high school for students recovering from addiction — as though it had sprung fully formed from the Realm of Pure Innovation.

What these all boil down to is shallow journalism, signs of reporting shortcuts that are, unfortunately, pretty typical.

Why does so much innovations coverage leave the reader asking questions and wanting more?

Why does so much innovations coverage leave the reader asking questions and wanting more?

One possibility is that covering these stories well requires additional legwork.

Rarely does a good solutions story fall in your lap. As freelance reporter Kate Rix has pointed out here in The Grade, you have to search — and, once you’ve found it, dig deep

Given how relatively rare they are, all the more reason for me to spotlight recent innovations stories that are surprising, detailed, and more deeply reported.

Each story I’m going to talk about approaches its subject in a different way, offering a discrete lesson in how to find and report on success within school districts.

One is a deeper look at a major issue that’s satisfying for readers and useful for decision makers looking to improve things in their own district.

Another compares efforts across two districts, exploring how one might inform the other.

The third emphasizes the unusual aspects of the district where experimentation is happening, both celebrating differences and cautioning against embracing the innovation as a panacea.

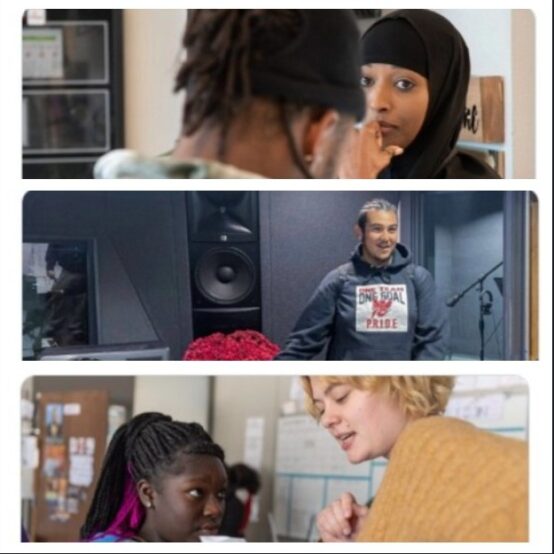

These stories have plenty in common — including that they come from nonprofit outlets and feature student voices — but their most winning common characteristic is that they’re deeply reported.

Rarely does a good solutions story fall in your lap.

Spotlighting enlightened leaders makes replication of success more likely

For this standout story, The Hechinger Report and the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting combined efforts to report on creative ways that districts in Arizona deal with students who miss class.

The story was published as a follow-up to their investigation, When the Punishment is the Same as the Crime, about districts that address absenteeism with a brute-force, one-size-fits-all solution: suspension.

An innovation story followed because the reporters, who used public records requests to collect reams of district-level suspension data, had the wherewithal to recognize bright spots in an otherwise sobering dataset.

What they found is that some districts rarely suspend kids for missing class, focusing instead on holistic fixes. And once they’d found those bright spots, they identified the people responsible for them, often enlightened administrators who’ve made it their mission to foster a culture that not only accepts but embraces the intervention in question.

An assistant principal calls the homes of struggling students not to dole out punishment but with curiosity about what might be holding those students back. A superintendent maintains a district culture in which every adult is expected to engage students by identifying the “skills and intelligence that exist in every child.”

By focusing on those changemakers, the reporters are giving readers a concrete model for how to start making a difference.

The one place I felt this piece was lacking was in its inattention to staff at schools with more punitive policies. Do those administrators see need for a change? The first article in the series does interview these folks, but I wish I better understood why they insist on sticking with a policy that by all accounts seems cruel and ineffective.

By focusing on those changemakers, the reporters are giving readers a concrete model for how to start making a difference.

How an honest review of a longstanding program can be a roadmap for a district just getting started

This story from Chalkbeat Tennessee comparing career academies in Nashville and Chicago is the ultimate follow-up in that it checks in on a longstanding initiative in Metro Nashville Public Schools.

It covers the successes and limits of Nashville’s 15-year-old CTE program – linking students to employers has been tougher than expected – and documents how those might be applied to a forthcoming similar program in Chicago Public Schools.

The follow-up is an essential piece to any solutions project because what makes a difference for kids is consistent success, not anomalies.

What really distinguishes this Chalkbeat piece, though, is its acknowledgment of and curiosity about the limits of the CTE programs it describes.

The Nashville program seems to have been successful in some key respects. High schoolers get hands-on work experience and industry certifications before graduating, and the district’s on-time graduation rate has risen since the program was implemented.

But the piece makes it clear that the district doesn’t track the data that could show if the approach is working. It also mentions an aspect of the program that’s only possible thanks to philanthropy, hinting at possible deficiencies in state and federal policy.

As a result, the key message of the piece isn’t “unequivocal success,” but rather “work in progress.”

One of the program’s most troubling challenges is that, when initiating a relationship with an employer, Metro Nashville Public Schools wants to “put its best foot forward,” so participating students must meet strict GPA and attendance requirements.

That excludes a lot of people. As one administrator quoted in the article puts it, “The students who need this the most are being left out.”

Because the Chicago program hasn’t really started yet, this piece isn’t so much a comparison as it is a roadmap of potential challenges, drafted from the experience of Nashville. Do they have a tracking system to measure effectiveness? What’s their strategy for partnering with local employers?

In this way, the article is directly engaged in helping one district find a solution to a problem that another district has been addressing for 15 years.

That’s a useful resource. Districts could use more such roadmaps — and education reporters could use the story to guide similar projects of their own.

The key message of the piece isn’t “unequivocal success,” but rather “work in progress.”

Asking what makes one success possible can lead to the discovery of more successes

On the surface, this Sahan Journal story is about how enrichment programs improve student attendance, but its approach turns it into a story about a lot more than just that.

Billed as an article about addressing chronic absenteeism, the piece about a Minnesota school is really about a school culture that allows for an effective response to problems like chronic absenteeism.

Rather than just reporting a success, the story takes a big step back and asks, how is this even possible?

In this case, the answer has to do with the way the school is organized.

The reporter looks at all the features of the school — from its community school setup to the way it incorporates student feedback — that made the enrichment programs both financially and culturally viable. In doing so, the reporter discovers opportunities to highlight other successes that have resulted from these unusual features.

We learn how staff quickly responded to student requests for more electives during the pandemic. (A CSI-style course is among the new offerings.) We learn about drones purchased for an enrichment program that are now being used to engage kids in math class.

Schools without those community-school features could certainly try to replicate Brooklyn Center’s initiatives, but it’s important for them to know about the enabling factors that run deep in the school’s identity, lest they interpret the success as easily scalable.

To its credit, the article makes that clear: “The Brooklyn Center School District is the only district in Minnesota in which every school is a full-service community school.”

Rather than just reporting a success, the story takes a big step back and asks, ‘how is this even possible?’

Like any other piece of reporting, solutions stories should be a pleasure to read

Let’s also take a moment to appreciate the Sahan Journal story’s lede, in which a group of middle schoolers attempts to solve a “murder” as part of Brooklyn Center’s CSI-themed enrichment program:

The killer must be the character with a pet spider, said 12-year-old Welma Williams. After all, poison had been involved in the murder; perhaps the murder weapon was spider venom.

“After all” — you can hear the 12-year-old’s matter-of-factness perfectly, even if that’s not exactly what she said.

Then, another student “led her assistant principal, Joshua Fuchs, and a Sahan Journal reporter to the hallway to share her findings, beyond the earshot of her classmates.”

The verb “led,” which conveys a formality in the girl’s bearing, depicts her as a precocious and committed student — as somebody who is clearly benefiting from the program the article will go on to describe.

That is some effective (and efficient) characterization. I could imagine the girl, and that’s what kept me reading.

I call attention to something so basic as a story’s opener because a piece without good writing is far less likely to be read, absorbed, and remembered — and because the writing in solutions stories is often didactic and dull.

This might have something to do with framing them as solutions stories in the first place.

We read — and write — solutions stories because, like medicine, some authority has declared them good for us (a message that The Grade, I’ll admit, proudly amplifies).

But we should also read them because they’re enjoyable in their own right.

There’s no reason reporting about a successful innovation can’t also include drama, rich characters, ambiguity, and other elements of a good story.

Previously from this author:

Why the National Reading Panel report didn’t fix reading instruction 20 years ago

Previously from The Grade:

Solutions stories that aren’t puff pieces (Kate Rix)

When good news goes missing (Karin Chenoweth)

Hope, agency, and dignity: how the education beat could save journalism (Alexander Russo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Will Callan

Will Callan is a freelance journalist based in Los Angeles. After freelancing as a print journalist in the Bay Area, he moved to Ann Arbor, Mich., and covered the first year of the pandemic at Michigan Radio. He’s since worked on podcasts, radio documentaries, and investigations at APM Reports. He can be reached at wacallan@gmail.com.